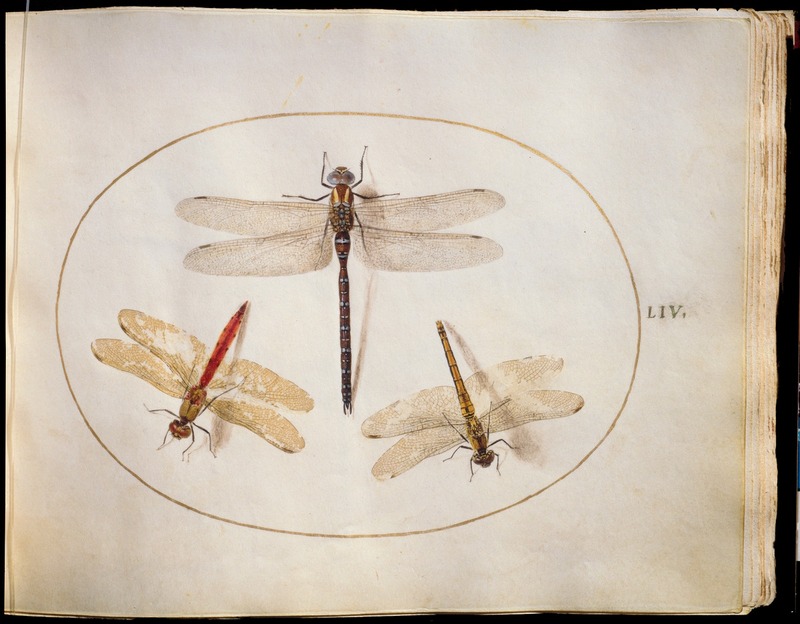

Ignis, Plate LIV

Hoefnagel, Joris "Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate LIV" from Four Elements, 1575. Watercolor and guache, 14.3 x 18.4cm. Washington DC, National Gallery of Art. 1987.20.5.55

Hoefnagel was one of the first people to elevate insects to be an independent pictorial subject. Previously, insects were researched extensively by Aristotle and Pliny, but it was not until Aldrovandi’s publication in 1602 that there was a printed and illustrated work talking exclusively about how insects related to science. Thomas Moffet worked on a collaborative compilation of knowledge that was published posthumously in 1634, titled Insectorum sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum (note 1). Throughout the years of insect studies, the Platonistic idea of a microcosm representing a macrocosm held fast. Accordingly, insects – a realm existing at the fringes of the familiar and the studied – pointed to something as large as God, the creator of such beings. Hoefnagel, a deeply religious man himself, was concerned by the dissonance created by the fact that insects were mysterious and not yet understood. Accordingly, he was the first to elevate insects into an independent pictorial subject (note 3).

In his Four Elements, the idea of insect elevation was furthered in the fact that Hoefnagel gave them the chapter relating to fire. It is the only chapter in which the title is not a description of their habitat, but rather a property that the specimens have in common. Insects were associated with an element that was beautiful, dynamic, wondrous, and itself embodying the ideas of death and life, tangible and intangible.

In Plate LIV, two dragonflies flank a third larger insect, all of different coloring. They refuse to acknowledge each other as they move towards breaking the edge of the surrounding golden oval. Their symmetry creates a perfect-looking picture: too perfect to be found in nature. It shows that Hoefnagel had such a comprehensive understanding of nature that he was able to manipulate it, extracting these dragonflies from their original context and putting them on a piece of vellum. They cast shadows, which invite the viewer to read the vellum page as a flat surface upon which the bugs stand, although there does appear to be inconsistencies within the shadows. These can be seen in the absence of shadows made from the wings, as well as the fact that the shadows in comparison to the dragonflies themselves vary in size and directionality, which suggests multiple light sources. This undermines the trompe l’oeil effect and shows a deeper intricacy to the space.

Hoefnagel pasted actual wings from a specimen onto the folio, emphasizing the fact that his depiction of the specimens are so close to real life that they cannot be distinct from nature itself (note 3). This also blurs the lines between art as visual pleasure and art for naturalistic study. His rendering is so exact that it can be studied akin to an actual specimen, from which the wings were taken. Hoefnagel leans towards naturalistic study rather than drawings for visual pleasure in Four Elements as insects are often shown from multiple angles and positions. Hoefnagel, already known as a master of art, exercises his knowledge of the scientific – and more specifically, entomologic – realm with every dragonfly that lies in wait for his chance to fly off the pages of Ignis.

Notes

note 1. The collaborators included Conrad Gessner and Thomas Penny. It was actually written at the same time that Hoefnagel was painting insect studies for Ignis. Hugh Raffles, “The Ineffable,” Insectopedia (2010), pp. 125-140.

note 2. For a more complete history of insect research, especially relating to the works of Aldrovandi and Moffet, please reference Janice Neri “Cutting and Pasting Nature into Print: Ulisse Aldrovandi’s and Thomas Moffet’s Images of Insects,” The Insect and the Image: Visualizing Nature in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1700 (2011), pp. 27-73.

note 3. Pasting insect wings into an artwork reflected earlier practices from Munich, Vienna, and manuscripts of Philip of Cleves. Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann “The Sanctification of Nature,” The Nature of Imitation: Hoefnagel on Durer (1986-1987), pp. 45-46.