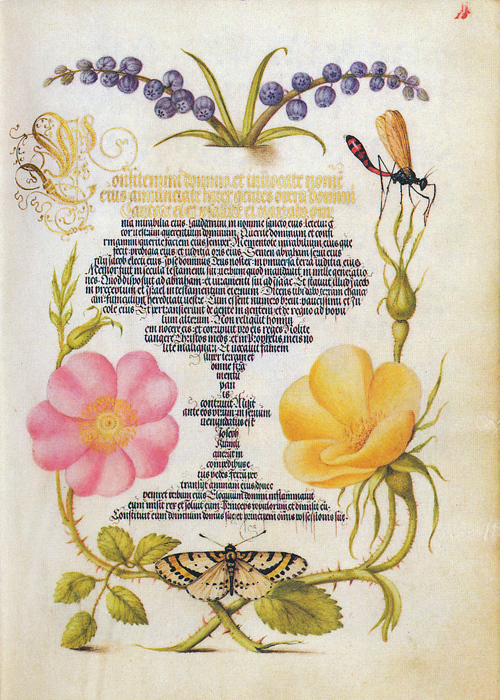

Folio 15

Hoefnagel, Joris "Common Grape Hyacinth (Growth Habit Unusual), Imaginary Wasplike Insect, Eglantine, Austrian Brier, and Magpie Moth" from Mira calligraphiae monumenta, 1561-1596. 14.3 x 18.4cm. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum. MS.20

The connection between human and natural world established in the first plate of Ignis also prevails in a work of Hoefnagel’s outside of Four Elements, when he illustrated a manuscript originally created to show off Georg Bocksay’s calligraphic skills. Hoefnagel combines something as human as words and writing with the natural world as he inserts flowers, fruit, and insects into the manuscript. Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta began in the early 1560’s as an exhibition of Georg Bocskay’s writing techniques. In the 1590’s, Emperor Rudolph commissioned Joris Hoefnagel to complete illuminations within its pages (note 1). It is doubtful that Bocskay originally intended for pictures to accompany his letters, but the resulting manuscript intertwines word and image in a masterful way that collapses the thirty-year gap.

In Folio 15, Bocksay fashioned his condensed Gothic script into the form of a golden-rimmed chalice. Hoefnagel’s illustrations around the lettering strongly relate to the writing in both shape and form (note 2). The thick and thin contrasts within the text can be found within the inclusion of thin leaves against thick and sturdy floral shoots, and the various thorns adorning the stalks answer each letter’s flourish. The bulging flowers on either side, their petals mimicking the diamond shaped decoration, offset the slender nature of the goblet’s stem. Hoefnagel also modified the growth pattern of the grape hyacinth on the top of the page, illustrating that he was so familiar with nature that he had the ability to modify and arrange it. It appears to emerge from a cleanly made cut in the sheet, exposing itself from within the vellum. Hence the page itself serves as both a flat surface where words rest and vines emerge, as well as aground upon which stems can support themselves. Hoefnagel is using these techniques to create a trompe l’oeil effect, and play with our visual perceptions of the page and its space (note 3). The flora imitates specimens; the left flower being open while the right is more closed. Doing this can be thought of as a parallel to displaying animals from multiple views in Four Elements, inviting a closer and more diagrammatical consideration.

The composition, through symmetry, bright colors, and a staged nature, has a definitively visual appeal, though assorted flora views acknowledges a naturalistic study undertone. The folio, and the entire Mira Calligraphae, puts the natural world into a space occupied by text serving as an exhibition of human prowess. It shows that there is a reflection and visual dialogue between the human world, represented here by text, language, and calligraphy, and the natural world, seen in lines and forms.

Notes

note 1. Lee Hendrix and Thea Vignau-Wilberg Nature Illuminated (1997), pp. 1-8.

note 2. Hoefnagel was of the belief that images were superior to text. Therefore, he did not create pictures that directly imitated the text, but rather complimented it. For more information about this, please see Lee Hendrix and Thea Vignau-Wilberg, Nature Illuminated (1997), pp. 49-56.

note 3. Trompe l’oeil effects ran rampant throughout Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta. Flowers can often be seen from both sides of a page, weaving through the manuscript, or drawn as if they had been pressed into the folio. Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, “The Sanctification of Nature,” The Nature of Imitation: Hoefnagel on Durer (1986-1987), pp. 45-46.