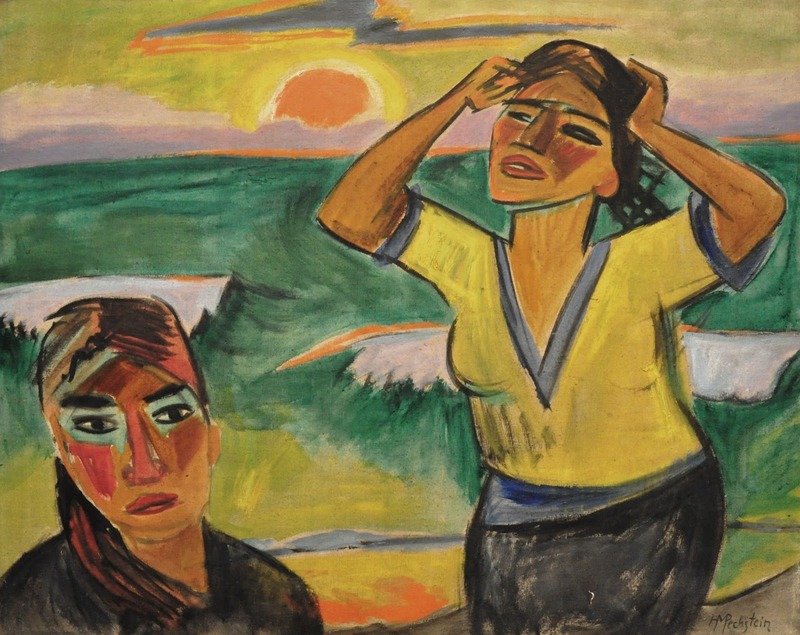

Max Pechstein "Sunset"

In 1906, Max Pechstein joined Die Brücke. This group, which included Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Otto Müller among others, produced raw, passionate paintings and woodcuts that hybridized urban and exotic themes. In Pechstein’s painting Sunset 1921 (Figure 1), the themes of modern and “primitive” compete with each other, creating a vibrant, restless aura. However, Pechstein intertwines the simplified forms of African and Oceanic sculptures with European laborers’ clothing, suggesting these cultures were closer to nature due to their unadulterated lifestyles. Set in an Arcadian escape for mankind, Pechstein reinforces the Western trend to strip so-called exotic cultures of their identity by arbitrarily splicing together mask-like features with rural European dress in order to suggest their otherness.

As the title suggests, Sunset depicts two female figures basking in the slowly setting sun. Although the painting is comprised of loose, expressive brushstrokes, it is formally structured — the gaze of the bottom figure follows the orange diagonal outline, which then draws the eye to the arm and the finally, the sun. The painting incorporates warm hues of orange and yellow, which are reflected from the atmosphere onto the women’s clothes and faces. The landscape, lush with greenery and calm pools of water, resembles a marshland thriving with life. Most forms are simplified to flat planes of color — sky, vegetation, water and figures distinctly separated by loose, orange boundaries of thin paint strokes. There is a hint of dirt at the bottom of the painting, which grounds the figure in space. Black dominates the lower half of the painting, and is used to outline the women. Shadows and highlights are simply rendered, resulting in a flat landscape. To create depth within the canvas, the women face opposite directions so that their gaze directs the viewer to the background and the foreground.

The first point of interest is the two female figures, whose ethnicities appear to conflict with their European dress. Pechstein travelled to islands of Palau in 1914, which was a German colony at the time. His trip was abruptly cut short by the outbreak of World War I, so his post-war work, including Sunset, is based from memory. While their dress, especially the standing figure, is distinctly Western, their skin color is not. Their complexions are a rich combination of ochre and burnt sienna, like those of the people of Palau. The lined, cotton tunic paired with a fitted skirt is more in line of European working class’s clothing, like that of laborers of farmworkers. This is also juxtaposed with their facial features, which are heavily influenced by Oceanic masks Pechstein encountered in Palau. Even the skin tone itself appears festively painted like that of masks, with a ring of turquoise around the eyes and war paint-inspired red splashes on the cheeks.

However, the slim almond-shaped eyes, linear brows, and long nose bridge are not elements exclusively found in Oceanic masks. Pechstein, who was the only Brücke member to receive formal training in painting, was active in Dresden, Berlin and Paris before Sunset was completed.[1] Before being drafted in the war in 1914, he was exposed to the Fauves’ appropriation of African masks that geometricized and simplified facial features like the brow, nose, and eyes to polygons and lines. This melting pot of various interpretations of the mask omits the historical context of their respective cultures, which allows “the mask [to] become a free-floating signifier for the past, present, future production of a given people, all of which remains unchanged.”[2] Pechstein also drew upon stereotypes of the rural peasantry in order to strengthen his ideology that these figures, free from modernity, were closer to their emotions and nature. Like other Bridge artist who tried to break free of the limits of bourgeois society, Pechstein used the rural culture for the same reasons as he did for appropriating the mask. This lower class, apparently limited in exposure to industrialization modernization, was seen as a group of simple-minded people. Coupling together the simple tunic with a non-Western identity proposes a parallel between these two cultures simply because of their supposed simplicity.

The romanticized idea that these exotic or rural cultures were closer to nature is exhibited in the euphoric pose of the women on the right. As she faces the glowing sun, her arms are up, tugging at her hair with her mouth slightly agape. This raw emotion is expected of these so-called exotic women, who exemplify two types of “otherness” —their gender and ethnicity. Besides belonging to a so-called primitive culture less advanced that European society, they are women, who are seen as more in tune with nature due to their childrearing abilities.[3] This concept of an untouched landscape with hyper-sexualized women feeds into the Primitivist ideology that non-Western cultures are more emotional and in tune with humanity's “roots.” This utopic world, filled with unbridled sexuality and possessive ritual dances, is simple, raw, and intense —exactly the stereotype of these non-Western, less advanced cultures.

These figures in landscape are not a return to a prelapsarian state — while non-Western cultures did not possess the technologies the West deemed advanced, they coexisted with European society, until their conquest and colonization. They were not an escape from modernity or a future state beyond modernity; in fact, their colonizers introduced and imposed modernity on them. However, Pechstein and other Expressionist artists like Kirchner saw the “others” as the hope for humanity to survive a rapidly industrializing and commercializing world.

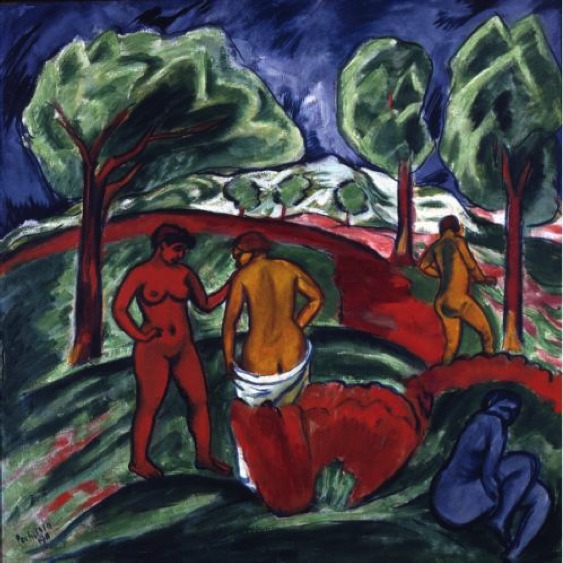

Pechstein’s travels to places that embodied primitive or simple ideals —Palau in 1914 and repeated visits to the Baltic village of Nidden—are both influences in the marshy, flat landscape of Sunset. However, the figures and the landscape are not specific to location or a moment in time. Pechstein’s Palau paintings were not rendered on site— he referred back to his travels before the war, making the figures lack context and identity. In a similar vein, Pechstein’s Day of Steel (1911) (Figure 2) depicts the modern nude in an Arcadian world. The bathers, whose ethnicities are also ambiguous, hover somewhere between civilized and primitive. In Sunset, depicting the non-Western figures with Western clothing not only alludes to the colonialist attitudes of the West but also equates the rustic with the “primitive.”

The contesting themes of modern and primitive are strong in Sunset — the setting, figures, and themes are a complex blend of Pechstein’s travels to so-called simple cultures and his influences a rapidly modernizing Germany. However, he strips the identity of the cultures he appropriates visual elements from by excluding historical context. Though visually appealing, the confusing assemblage of figures fulfills the warped primitivist romantic idea of non-Western’s people’s ostensibly intimate relationship with nature. Lacking individualistic features, Pechstein’s depiction of these women only serves to reinforce generalized stereotypes about the rural and the “primitive” — that their simple lifestyles could somehow revitalize a stagnating art academic world and bourgeois society with their raw connection with their emotions and nature.

[1] Aya Soika, “Max Pechstein: Outsider or Trailbazer?,” in New Perspectives on Brücke Expressionism, ed. Christian Weikop (Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011), 163.

[2] Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, “Primitive,” in Critical Terms for Art History, ed. Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff, 2nd ed. (University of Chicago Press, 2003), 218.

[3] Ibid., 221.