Browse Exhibits (70 total)

20th Century Pessimism: Examining Emotion in Expressionist Portraiture

Welcome! Please note that this exhibition may have functionality issues or require maintenance. Please visit the Washington University Libraries Digital Exhibitions page to browse other exhibitions or report problems with digital exhibitions.

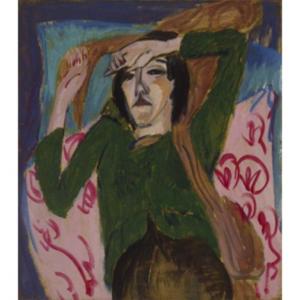

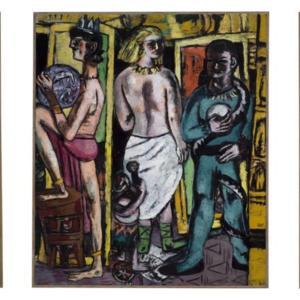

The Expressionist movement in early 20th century Europe reflected a change in the mindset of artists; the tension caused by political and social developments of the time induced a shift away from the rigidity of academic guidelines toward the freedom manifested in abstraction and subjectivity. Germany and France, two countries particularly transformed by the impact of the World Wars, harbored artists who strived to communicate the atmosphere of the time through painting. Although it is a traditional genre, portraiture is especially relevant when examining the effects of cultural changes on modern art, being that the distinct portrayal of facial expression and body language provides a more explicit insight into the emotions of the artist. In combination with Expressionism, a style indicative of distinct artists in its inherent subjectivity, the genre of portraiture highlights the effects of conflict on the individual. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Woman in a Green Blouse (1913), Max Beckmann’s The King (1937) and Georges Rouault’s Chinois (1939) all exemplify the potency of expressionism in conveying cynicism and despondency through the artists’ distinct approaches to abstract portraiture.

All three artists suffered the effects of pre- and post-war European society in the 1900s in ways that defined the trajectory of their artistic careers. Kirchner painted Woman in a Green Blouse right before the first World War, after the dissolution of The Bridge (Die Brücke), the group of Expressionist artists he had co-founded in 1905. The painting is reflective not only of the artist’s angst regarding a significant event in his life, but also of the strain on society caused by the impending war. The distress imparted to the viewer by the position and expression of the woman, composed of short, abrupt brushstrokes, emphasizes the presence of Kirchner’s emotions within the painting. Both Kirchner and Beckmann fell victim to the Nazi Degenerate Art movement, which severely restricted their ability to succeed as artists in Germany.

The rejection of Beckmann’s work by the Nazi government in the 1930s is represented in the transformations he made to The King over a period of four years; the painting is a self-portrait that depicts the artist and his wife, and the dominance of black paint within the composition emphasizes the dark shadows that express Beckmann’s dejection regarding his exile. Rouault’s piece also speaks to the theme of negativity: his illness in the early 1900s in conjunction with his experiences as an outsider in society brought about a new perception of the human condition, and his paintings thereafter expressed a concern for the suffering caused by societal transformations. Chinois is indicative of the dismal aspects of the 1930s, nearing the onset of World War II, in that it comprises thick, heavy strokes of somber colors, and the viewer’s inability to fully see the eyes of the figure creates a sense of ominous mystery.

Though their styles and techniques differ considerably, Kirchner, Beckmann, and Rouault are linked thematically in their approach to their respective portrait paintings. The three European artists are undoubtedly embodiments of Expressionism, due to their color choices, which appear instinctive rather than imitative in order to convey emotion, and the varying degrees to which they abstract faces, figures and objects. Their methods of depicting the human figure within a context exude different elements of pessimism, from melancholy and anguish to indignation and discontent. The King, Woman in a Green Blouse, and Chinois epitomize portraiture of the first half of the 20th century in demonstrating how artists were influenced by the negativity invoked by the repercussions of political, social, and cultural change.

30 Years of Achievement: Our Names and Our Stories

30 Years of Achievement: Our Names and Our Stories is an exhibit that celebrates the life of Dr. John B. Ervin, the university’s first African-American dean and celebrates the John B. Ervin Scholars Program, 1987-2017. The physical exhibit was located in the Gingko Room, Level 1 of Olin Library in the fall of 2017.

The exhibit coincided with an event celebrating the 30th Anniversary of the Ervin Scholars Program, “Measuring the Impact and Influence of Ervin Scholars” on September 15, 2017 in Graham Chapel. The alumni’s careers span government, public service, international affairs, social media, entrepreneurship, medicine, research, and public policy.

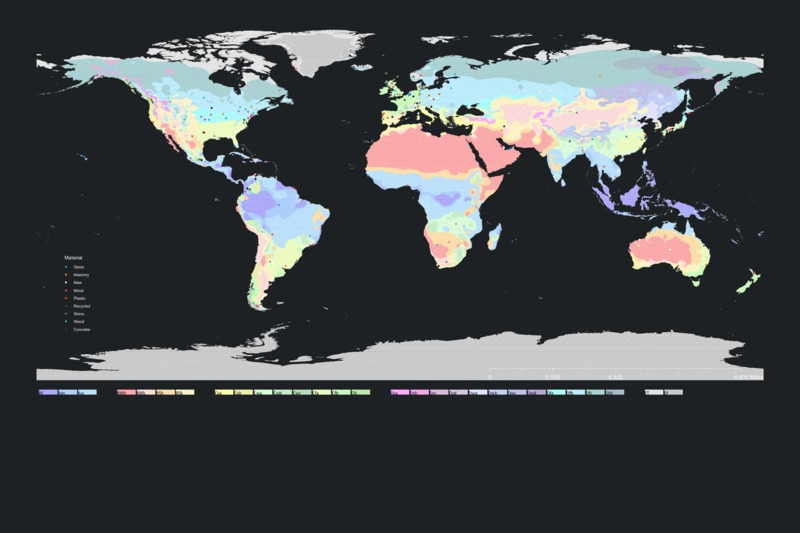

434M Fall 2018

The materiality of architecture highly related to the environment where it is located.Due to globalization, the materials we choose and the technique we apply are no longer limited to a small range. What is the relatively current relationship between building materials and the climate? What are the major materials we are using today and its application distribution in a global scale? Many of these similar questions is important for us to understand where we are in these complex conditions. More crucial, both the climate and architecture are changing and evolving. How should architecture respond to the climate changing into a new normal? This exhibition aims to provide an incomplete and brief view of the materiality world in architecture and construction. The projects are selected from around 300 case studies the students produced this semester.

A Culture of Cultivation: Flower Still Lifes from the 17th Century to the Present

Flowers encompass only one category within nature, as well as one category within the genre of still-life paintings. Flower still lifes from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries encourage an exploration of the rapport between art and nature and invite us to contemplate the distinctions between the two. These paintings actively court a desire to remember, and yet, forget that their subject belongs to the real world. Emulating nature through art dominated the creative discourse during this period. Artists possessed an ambition steeped in the confluence of science and art and the mergence of botany with craftsmanship. Investigating these paintings, in all of their botanical and artistic glory, stimulates discussion about the culture out of which these pieces were born.

By beginning with a twenty-first-century example of a still-life photograph of flowers, this exhibition may seem unconventional. However, this regressive chronological approach allows for a more holistic understanding of the genre of flower still lifes and directly addresses the question of why artists of today continue to garner inspiration from the works of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch still-life painters. How and why do these Dutch flower paintings endure as bastions of artistic genius? After all, flowers eventually fade and wither. While the viability of blossoms remains unavoidably transient, the vitality of art lives on, proving that art outlasts the rhythm of nature. A closer examination of a few select flower still-life paintings from this period exposes the fact that flower paintings function as powerful works of art. They are more than images of mere beauty, and they offer more than an aesthetically pleasing arrangement of petals and buds. This exhibit, A Culture of Cultivation: Still Lifes from the 17th Century to the Present, investigates what it is that constitutes their more complex meaning, and it delves deeper into what lies beneath the petals and stems. From the work of Jan Brueghel the Elder in 1606 to the contemporary work of Paulette Tavormina in 2009, the genre of floral still-life paintings is undoubtedly far-reaching and transcends the historical boundaries of a bygone era. Dutch artists, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Adriaen van Utrecht, and Rachel Ruysch, left an indelible mark on the canon of flower paintings, and today Tavormina boldly preserves their legacy through a photographic lens.

To be sure, this exhibition merely scratches the surface of a long, rich history about the genre of flower still lifes but still celebrates the vitality of flower still-life paintings, as well as their impressive legacy within the world of art. This exposition offers an opportunity for its visitors to be transported back to the seventeenth-century Netherlands. Most importantly, however, it encourages an exploration of the possibility that these paintings do, in fact, represent more than natural beauty and symbolize more than the transience of life. To be sure, the works of this exhibit, as well as those belonging to the genre at large, are infused with a deep sense of culture and cultivation, and it is these qualities found within the works that cannot be understated.

A Vision in the Forest: Nature Works on Paper by Albrecht Dürer

The German native, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), was the most innovative artist working north of the Alps during the Renaissance. His technical skills were unparalleled, and by 1500, only a few years in to his artistic career, he was already acclaimed as the German Apelles. He is renown as the artist that revolutionized the art of printmaking, yet he experimented with multiple types of media, and some of his greatest contributions are his drawings and watercolors. Emperors, artists, and private collectors consumed Dürer’s valuable artworks at an international level during and after his lifetime. Dürer engendered a phenomenon known as the ‘Dürer Renaissance’ that involved the avid imitation and emulation of his works in the latter stages of the sixteenth century. Dürer achieved to convey details with delicate precision in his prints and watercolors, and court artists were commissioned to imitate his style and copy his works.

Nature is the setting for witnessing a spiritual vision in the story of St. Eustace, and for someone who admired nature as greatly as Dürer did, it also served as the principal source of guidance for his artworks throughout his career. In his writings, Dürer declared every element in nature beautiful and worthy of artistic study. His fondness for nature led him to produce nature studies as independent works of art, a practice that was nascent at the time. The current exhibition showcases Dürer’s famous engraving St. Eustace (c. 1501) as its centerpiece. By juxtaposing St. Eustace with various independent nature studies that Dürer produced, this exhibit endeavors to reveal the process behind the artist’s creation of complex and multi-faceted masterworks for dissemination in print.

In his quest to represent God’s creations, Dürer observed nature minutely in order to understand it to the best of his knowledge. During the Renaissance, recreating an object or artwork directly from nature was a key factor in validating its authenticity as being true-to-life. Some artists enjoyed more success than others at creating lifelike images. Dürer’s methodology consisted of bringing his working tools outdoors, and visualizing his subject firsthand – away from the studio – an approach he undertook before natural historians adopted it for scientific learning. This allowed Dürer to capture the subtle nuances of nature and to present details in his works in a refined manner, even if he polished his images in his workshop afterwards. Viewers can readily engage with his works because they figure man’s presence in nature. Dürer did not produce studies from life for scientific purposes but rather in order to glorify nature [and God] through his own artistic study.

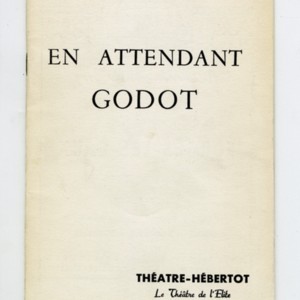

“if you could finish it…”: Beckett’s Revisions and Autotranslations

This digital exhibit features scans from a number of Samuel Beckett’s original notebooks, manuscripts and typescripts in both English and French. These pieces offer fascinating insight into the evolution of Beckett’s works across multiple drafts and two languages.

The physical exhibit "If you could finish it..." accompanied Connecting Contexts: The Modern Literature Collection and the Letters of Samuel Beckett in Olin Library in 2019, also now a digital exhibit.

Al Parker : the student

During Al Parker's enrollment in Washington University's School of Fine Arts from 1923 to 1928, he contributed to some of the university's publications. Below are links to selections of these illustrations from the holdings that are located in University Archives.

The finding aids for both The Hatchet, the Washington University yearbook, and The Dirge, a student publication, are available through University Archives.

Additional material, including Parker's original artwork, concept sketches, and tear sheets, are held at the Modern Graphic History Library. The finding aid for this collection is available online.

Arcimboldo's Gift: The Fantastical Beginnings of His Composite Portraits

The great painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo created numerous pieces in his time at the courts of his patrons Maxmilian I and Rudolf II, but left a legacy primarily in a single, inventive category of painting: composite portraits. Painstakingly composed of individual studies of nature and living things that together create the human form, Arcimboldo’s composite heads created a new intersection between the scientific study of naturalia and the age-old practice of painting the human figure. Like the kunstkammers and wunderkammers of the time, Arcimboldo's paintings managed to combine the natural, the artificial and the fantastical in singular compositions that did not have a contemporary comparison. Since their conception, Arcimboldo’s composite portraits have captivated, amused and puzzled centuries of viewers.

Arcimboldo’s earliest composite paintings date back to two series completed in the 1560s: Four Seasons, finished in 1563, and Four Elements, finished in 1566. Four Seasons represents Arcimboldo’s first foray into composite portraits. Comprised of four separate paintings, each image represents either a man or woman composed of the various crops available during that season. Four Elements, like Four Seasons, draws its inspiration from a similar theme. Rather than finding its pieces in the earth, however, Arcimboldo draws from the animal world to create its series of figures.

While at first glance the only relation between these two series is in their conception as composite portraits, there is more to their interaction and presentation as one. In 1569, the two series, accompanied by a poem composed by G.B. Fonteo, were given as a gift to Arcimboldo’s patron, the Hapsburg emperor Maximilian II. Through this gift, the two series interact not only with the viewer, but also with each other. Portraits that previously existed as singular entities in their own set can now be presented as pairs that cross series, genders, elements, seasons and placement. Presented as the sole focus of an exhibition for the first time, this is Arcimboldo’s Gift.

Art to Enchant: Illustrators & Shakespeare

We invite you to view a wide range of illustrated editions of Shakespeare from 1744 through 1986. Illustrators were challenged by the texts of this great dramatist, whose works were already visually represented on stage. See how they responded to this challenge, and whether or not they were successful, in this fascinating selection of books

With an essay by Douglas Dowd, Professor of Art and American Culture Studies, and an Introduction and Checklist by Anne Posega

Beckmann's Balance Board

As early as 1909, Max Beckmann was regarded as one of Germany’s most promising young artists. After graduating from the Kunstschule in Weimar, Beckmann began his career working in a style of history painting that was rigorously academic in comparison to many of his Fauvist and Cubist contemporaries. However, following the end of the First World War, Beckmann left much of his academic training behind to pursue new paintings imbued with a graphic flatness and a warped sense of space.[i] Throughout this transition toward a more avant-garde aesthetic, Beckmann resisted pure abstraction, remaining uniquely grounded in capturing the world of objects within his canvases.

Due to his commitment to representation Beckmann was, and still is, deemed an “unflagging picture maker” among a throng of artists tending toward the abstract call of an increasingly modern art world.[ii] In addition, Beckmann has been hailed for the role he played as the “moral commentator” and chronicler of his time, especially as the necessity for such a figure grew during the rise of the National Socialism and The Third Reich.[iii] During this chaotic period, his idiosyncratic pictures aimed to document and make sense of the full range of the world around him, from the whimsy of the circus to the sinister darkness of bondage, sacrifice, and torture, at the hands of violent oppression.

Among the numerous achievements that solidify Beckmann’s role in the canon of art history, Klaus Lankheit highlights a central element of the artist’s late studio practice, describing him as a maker of characteristically “unstable space[s].”[iv] Visually prominent in a number of the works catalogued in this exhibition, this instability plays an immense role in the creation of the uncanny power his works exude. In many of Beckmann’s works, the compositions are riddled with objects and characters that defy gravity to stand upright, many of which feel as if they may fall out of the picture plane all together.[v] In addition, Beckmann imbues compositions such as The Acrobats (Cat. 1) with an odd perspective in which subjects appear to be precariously balanced on top of each other rather than situated behind one another in retreating space. However, the creation of unstable-looking images through the visual strategies of shallow pictorial space and an awkward stacked perspective, constitute only one of the ways Beckmann builds his fragile and unstable universe.

In addition to these clever formal devices, Beckmann utilizes a number of methods deeply buried within the conception of his images to create his signature sense of tumult. Beckmann’s The Acrobats highlights the manner in which he destabilizes his images and contemporary notions of time and identity through conflating the modern world with the fictional realm of the stage. Portrait of Valentine Tessier (Cat. 2), an abstracted representation of a famous French actress,underscores his use of a fluid balance of abstraction and representation to bolster the instability present in his paintings. Furthermore, Artists with Vegetables (Cat. 3) stands as an example of the instability provided by Beckmann’s ambivalent worldview, characterizing life as an ambiguous and incongruent mixture of utopia and dystopia. In particular, this work demonstrates his desire to actualize a form of utopia similar to those of his contemporaries and predecessors like Matisse and the first generation of Expressionists, while simultaneously looking skeptically at the possibility of achieving this goal. These paintings, bolstered within this exhibition by Beckmann’s Paris Society, The Actors, Carnival Mask, Film Studio, Falling Man, and Sunrise, exhibit the various strategies Beckmann employed to destabilize his work.

[i] Christian Lenz. "Beckmann, Max." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed May 5, 2015, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T007231.

[ii] Charles S. Kessler, Max Beckmann’s Triptychs (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1970), 1.

[iii] Kessler, Max Beckmann’s Triptychs, 6; Haxthausen characterizes Beckmann similarly here: “In 1912…to them,” Charles W. Haxthausen, "A Poetics of Space: Beckmann's Falling Man," Max Beckmann ed. Sean Rainbird (New York: Museum of Modern Art : [Distributed in the United States and Canada by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers], 2003), 250.

[iv] Kessler, Max Beckmann’s Triptychs, 6.

[v] Max Beckmann, Carnival Mask, oil on canvas, 1950.