Little Black Sambo (1921)

Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

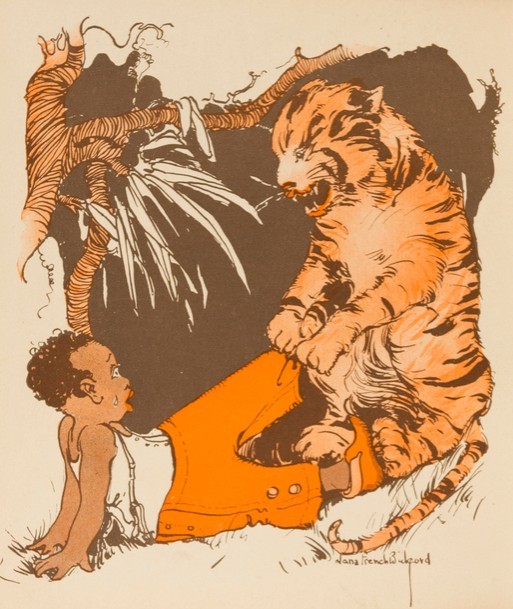

The sentimental child as an essential representation of American childhood came to dominate children’s literature in the late nineteenth century, a legacy indelibly tied to Little Black Sambo. Sentimentality allows for the reader to empathize with the child in the story, thus identifying a part of themselves with (white) children. Using Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a framework for childhood sentimentality, Anne Duane asserts that white children receive compassion. She states, “Little Eva wrung tears and won hearts because she suffered,” directly linking the tears of white children to empathetic responses (1). This is contrasted with black children’s tears, which Robin Bernstein suggests are usually met with indifference by most white readers (35). Sambo’s tears gesture toward traditional representations of the sentimental child, yet the context of the image prevents the white viewer from empathizing with Sambo.

Just as this 1921 version of the story illustrates, Sambo sheds at least a tear in most editions of this book, and in this image he looks especially troubled. His vulnerable position in the illustration, as a tiger attacks him, places him within a larger context of endangerment. Sambo is depicted without parental supervision in an exotic jungle, the black backdrop behind him insinuating the unknown depth and danger of the forest. The tiger dangerously looms over Sambo, unnaturally sitting on its back legs as it steals Sambo’s pants. The tiger’s facial expression is markedly sinister and monstrous, heightened by the fact that it appears to make direct eye contact with Sambo. In reaction to this, Sambo cries while lying on his back in a defenseless position, attempting to prop himself up and looking into the face of danger. It is obvious that Sambo is scared of the tiger, and his tears signal his fear.

Although the image has all the trappings of the kind of image that calls for empathy, there is a key feature of sentimentality missing: evidence of physical violence. The tiger is clearly a wild animal, strong enough to drag Sambo across the jungle floor. Yet, Sambo does not sustain any injuries that would suggest he is in pain, an aspect to sentimentality that Elizabeth Barnes notes is essential: “In the sentimental scenario, true personhood is attained not by social elevation but by encounters with pain, encounters to which the ‘strong’ have access via their empathy with the ‘weak’: through their identification with the suffering victim, even the empowered gain ‘authentic,’ ‘Christ-like’ subjectivity” (1). Despite the more realistic and cute depiction of Sambo in this image, his lack of physical injury and obvious pain prevents him from embodying the sentimental child figure. The white reader does not identify with Sambo’s character as he is depicted as physically unfeeling in the face of violence and danger, something that takes away from his status as a character deserving of empathy, childhood, and humaness.

Barnes, Elizabeth. Love’s Whipping Boy: Violence and Sentimentality in the American Imagination. University of North Carolina Press, 2011. Print.

Bernstein, Robin. Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights. New York: New York University, 2011. Print.

Duane, Anne Mae. Suffering Childhood in Early America: Violence, Race and the Making of the Child Victim. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011. Print.

Citation

Catalog Search

Search for related records in these catalogs: