Sam and the Tigers (1996)

Dublin Core

Title

Description

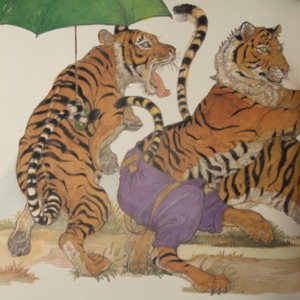

This scene from Little Black Sambo, which depicts the tigers fighting with each other over Sambo’s clothes, is closely related to a long history of the African depicted as a trickster or a humorous person. In this scene, Sambo has just successfully convinced the tigers to turn on each other in order to escape them. The tigers fight each other into oblivion, eventually turning into butter, and Sambo is able to retrieve his clothes and take the butter home for a pancake dinner with his mother. Joseph Boskin, author of Sambo: the Rise and Demise of an American Jester writes, “throughout the slave period and beyond, Sam was one of the names whites applied to someone they thought comical. Sam and Sambo were obviously too close for the transition not to have occurred” (38). This scene illustrates the humor with which Helen Bannerman, author of Little Black Sambo, created Sambo and this analysis will look at ways this humor makes Sambo less threatening to white audiences.

The way Sambo not only escapes destruction but also outwits his would-be destroyers in this scene can be read as the allowance given by whites to the African trickster to exist in a context that would maintain whites’ security over their slaves. On the topic of African trickery, Boskin writes, “thus those natural humorists (…) were enabled a gift of nature to cope with, even overcome their enslaved condition” (63). The slave got away with it because “whites were obviously buoyed by this particular image because it assuaged whatever guilt might have burdened them” (63). Sambo as a trickster therefore served a dual purpose; whites could rest easy with the idea of the buffoon slave while also mollifying their conscious concerning the enslavement of people.

As a result, Little Black Sambo becomes a cathartic project for the anxious white, soothing fears of malicious black behavior by portraying Sambo as a trickster. Sambo as a humorist bloomed into a highly lucrative minstrelsy business; the black comical act, in which blacks were made to be entertaining rather than frightening, was highly popular and highly profitable. Boskin proposes, “the comic black: clever but not dangerous, and always capable of performing” (100). This idea underscores the white community’s desire to utilize an outlet for disseminating their concerns regarding a rebellious or disobedient slave.

Rather than behaving disobediently, Sambo is acting endearingly clever and content with his ability to escape being eaten by the tigers. Boskin makes the point that; “the minstrel sustained the image of black as possessing a unique connection to happiness” (82). This theme is evident in Little Black Sambo by the way Sambo gets his happy ending; he is able to avoid being eaten, while at the same time can trick the tigers and come home with butter for a bountiful pancake dinner. Boskin postulates, “blacks had the ability to easily hide their feelings and could act out whatever might be necessary for the moment” (99). In this scene, Sambo is able to control his fear of the tigers and negotiate a situation in which he emerges as the victor. The "Little Black Sambo” storyline consequently preserves trickster Sambo in a context that is playful enough so as to ensure the white community only derives pleasure, not panic, from his story.

Boskin, Joseph. Sambo: The Rise & Demise of an American Jester. New York: Oxford UP, 1986. Print.