Browse Exhibits (70 total)

The Kunstkammer: An Art of Serious Play

The incidence of play is not associated with any particular stage of civilization or view of the universe. Any thinking person can see at a glance that play is a thing on its own, even if his language possesses no general concept to express it. Play cannot be denied. You can deny, if you like, nearly all abstractions: justice, beauty, truth, goodness, mind, God. You can deny seriousness, but not play.

Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens (1950)

In sixteenth and seventeenth-century Europe there arose a phenomena of collecting and displaying all manners of objects and artifacts known or discovered at the time. Such collections comprised natural specimens, man-made objects and so-called “curiosities.” The patrons of these “cabinets of curiosities” were as varied as the objects themselves. From botanists to philosophers, aristocrats to priests, the fervor to obtain and study these items affected all who possessed access either through wealth or association with a royal courts or universities. The collections themselves were no less multifarious; some focused on a specific interest such as geology, while others embraced a more encyclopedic spirit. Equally diverse, as well, were the modes of display, from small cabinets to multiple rooms, and even entire gardens.

Yet what defined these collections – known variously as Kunstkammer, Wunderkammer, or studioli? What set them apart from merely being assemblages of artifacts or luxury goods? The answer lies in the objects themselves, in the heightened sense of interaction – of play – both within and among the items, and most of all with the viewer.

The objects in this exhibition evince, both on their own and in dialogue with surrounding works, the polarities and complexities of the Kunstkammer as a mutable and polyvalent space. Each item displays multiple playful blurrings of seemingly dichotomous concepts, from obvious juxtapositions of naturalia and artificia to subtler exchanges of domestic versus exotic.

While this exhibition concerns specifically the phenomenon of the Kunstkammer and the zeal for wonder prevailing throughout Europe during that time, this investigation is no less relevant to contemporary society. It offers not only a new perspective with which to consider objects, museums, and collections of all sorts, but also a heightened awareness of the “play” element in our own lives. As in the kunstkammer objects, evidence of such an inherent fun in playing may be found in popular social phenomenon such as Pinterest or even internet memes, where recycled texts and images are wittily combined and recombined. As the philosopher and playwright Friedrich Schiller once mused in Letters Upon The Aesthetic Education of Man (1794), “Man only plays when in the full meaning of the word he is a man, and he is only completely a man when he plays.”

The Louise de Coligny-Châtillon Letters

A collection of letters written by Louise de Coligny-Châtillon to Guillaume Apollinaire between February 1915 and September 1915.

The Modern Bathers

The bodies of nude bathers and the landscapes that they are portrayed in have been a platform for exploring of humanity’s relationship with the natural world. Fauvist and expressionist painters, including Henri Matisse, André Derain, Max Pechstein, and others have explored nature and humanity through this motif as well, but these modernist artists have also departed from the traditions of the bather scene, and have used it as a vehicle for the expression of their own subjective styles and ideas. Through examining the paradisiacal environments and bather scenes of French and German expressionist artists, this exhibition will reveal the modernist techniques, ideas, and historical milieu that both engage with this traditional subject and re-conceptualize it with new modernist techniques.

Max Pechstein’s Day of Steel is a seamless introduction to this exhibition, as it displays a very traditional landscape and figural composition, and because the artist actively engages with the work of his predecessors and that of his contemporaries in order to achieve this idyllic scene. Day of Steel features many recognizable art historical tropes, including classicized female nudes, the turbulent grey and white sky reminiscent of El Greco’s View of Toledo (1596, fig. 4), as well as the thick brushstrokes and contours of Van Gogh’s landscapes. These references are also remixed with truly modernist brushwork and coloring, and also a reference to Henri Matisse’s blue nudes in the right corner. Much Max Pechstein’s work is highly influenced by his place in art history as well as his place among his contemporaries, and all of these elements thus combine in order to produce the anxiety and wariness that this particular bathers scene provides.

Matisse’s Bathers with a Turtle (1907-08, fig. 2) brushwork, coloring and subject matter are similar to Day of Steel, but in this painting the viewer very clearly sees the drastic departure from the traditional bather landscape. The landscape itself is reduced to large, affective color blocks that both collapse any depth in the painting and draw all attention to the shapely, deformed bodies of the bathers. These bathers, like Pechstein’s, are removed from all society and modernity, and while this was a common idea in Arcadian landscapes, Bathers with a Turtle isolates the bathers from the tropes of the motif itself. Their strange, lumpy bodies and the isolating background give the painting a surreal vibe, and reflect Matisse’s own development as a painter in response to the changes in art and during the time he worked.

Lastly, Max Beckmann’s Lido (1924, fig. 3) presents quite a different take on the subject of bathers. Beckmann shows a leisurely beach scene on the coast of Italy, a scene that is not directly a reference to primitivist Arcadias or traditional bathers, but one that is similar to the other two works in this exhibition in the way that it depicts figures interacting in an environment. The green waves in the painting resemble the contoured topography in Day of Steel (1911, fig. 3), and the bodies of the swimmers are immersed and positioned in this flattened environment in an almost surreal way. Lido presents the modern world which painters like Matisse and Pechstein attempted to leave through their depictions of bathers and Arcadias, but Beckmann’s piece able to emit a similar energy and wariness of style and art history as Day of Steel and Bathers with a Turtle. The juxtaposition of Lido with the other more primitivist works provides an interesting perspective of modernity as it is explored through the bather motif.

The Monster's Library

Dante Alighieri, L’enfer, illus. Gustave Doré, trans. Pier-Angelo

Fiorentino (Paris: L. Hachette et cie., 1865)

A Book Made of Books: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

An exhibition curated by students enrolled in Frankenstein: Origins and Afterlives taught by Dr. Amy Pawl and Dr. Corinna Treitel, Fall 2017 – Spring 2018.

Olin Library, Special Collections

Washington University in St. Louis

This exhibit, The Monster’s Library, celebrates the 200th anniversary of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). Only eighteen when she began the novel, Shelley recalled its genesis as a “waking dream” that occurred after her friend Lord Byron invited a small circle of friends, including her future husband Percy Shelley, to participate in a storytelling contest. While Shelley powerfully describes the unbidden vision of the “pale student of unhallowed arts” that appeared to her in the night, it is clear that her work is also the result of years of serious and expansive reading. Shelley’s subsequent reference to her completed book as her “hideous progeny” invites us to see the parallels between her creative work and Victor Frankenstein’s. Just as the creature’s body is made up of previously scattered parts, Shelley’s creation is a book made up of other books. To investigate the remarkable intertextuality of Shelley’s project, students in Frankenstein: Origins and Afterlives have identified three “Libraries” within the novel itself. The most literal of the three, “The Creature’s Library,” consists of the volumes that the abandoned creature finds in a satchel and uses to craft his humanity in the absence of his creator. “Victor Frankenstein’s Library” collects scientific and poetic works referenced by that creator, while “The Author’s Library” displays influential writings by Shelley’s family members and others. The discoveries our students present here are a reminder that libraries and special collections continue to be laboratories of innovative research today.

Acknowledgments

The Monster’s Library, a special exhibit at Olin Library, is a student-curated exhibition of materials in Special Collections at Olin Library and the Becker Medical Library at Washington University in St. Louis. The following students enrolled in IPH 450A: Frankenstein, Origins and Afterlives explored the library collections in meaningful ways: Lisa Brune, Fritzi James, Elliott Crosland, Jack Stephens, Victoria Rabuse, Griffin Reed, Nate Rickard, Deborah Rookey, Yixin Huang, Rachel Brace, Kate Taub, Julia Kim, Anna Lin-Schweitzer, Anne Seul, Joshua Leopold, Rachael Butler, Kristen Sze-Tu, Maya St. Clair, and Noelle Darling. Drs. Amy Pawl and Corinna Treitel incorporated hands-on experiences with primary materials in their course curriculum. Our objective is to pave the way for students to serve as campus educators, sharing their knowledge of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein with exhibition viewers.

Every exhibition is a collaborative effort dependent upon the skills and commitment of numerous individuals. The exhibitions program benefits from the unfailing support of Denise Stephens, University Librarian, and Nadia Ghasedi, Associate University Librarian for Special Collections. Dr. Garth Reese, Head of Curation for Special Collections, and Cassie Brand, Curator of Rare Books, lent their expertise by scouring the collections for relevant material. Joel Minor, Curator of Manuscripts, assisted with the letters in the exhibition. Elisabeth Brander, Rare Books Librarian at the Becker Medical Library, supplied thoroughly illustrated medical treatises for the students to peruse. She also kindly loaned a number of rare books and a model brain. Ian Lanius, Curatorial Assistant, designed the catalog and promotional materials. Kate Goldkamp, Curatorial Assistant, and Alison Carrick, Reference and Outreach Supervisor, assisted with every step along the way. Finally, we would like to thank the students in the Frankenstein course for their eagerness to investigate the library collections and for their contributions to the exhibition and catalog.

-Dr. Erin C. Sutherland

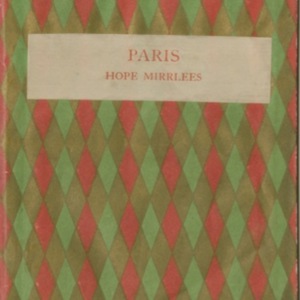

The Paris Project

DRAFT: NOT FOR CIRCULATION

The Paris Project is a digital edition of Hope Mirrlees's groundbreaking modernist long poem, Paris. The first edition of the poem was hand-printed by Virginia Woolf and published in 1920 by her Hogarth Press. A century later, this digital edition presents a diplomatic transcription of the original text alongside scholarly notes, contemporary images, and contextual essays.

The Philip Mills Arnold Semeiology Collection of the Washington University Libraries

Housed in the Special Collections of the Washington University Libraries, the Philip Mills Arnold Semeiology Collection contains approximately 1600 volumes on the history of signs, symbols, and communication.

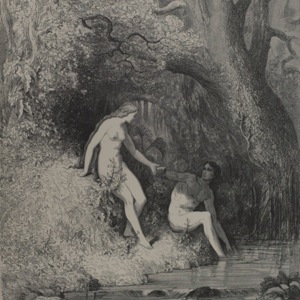

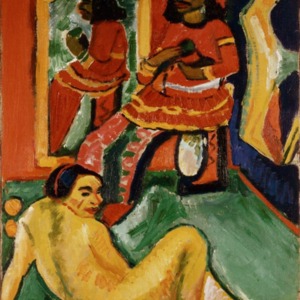

The Primitivist Nude in the Tradition of the Bridge

In 1905, four men came together to begin an art movement that would majorly shift the portrayal of the female nude in Europe. United by a desire to be closer to nature and to find self-understanding beyond urbanized Germany, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff formed The Bridge artist group in Dresden in 1905. They were later joined by Emily Nolde, Max Pechstein and Otto Müller. In the early twentieth century, the members of the Bridge congregated in Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s bohemian-style studio. They met to draw and share ideas with one another, all desiring radical change in the art community with respect to non-naturalism. They traveled together to the lakes in Moritzburg outside of Dresden in order to paint nude subjects in a green landscape, integrating humans into a natural environment. Kirchner referred to the group as “one big family.”[1]

All the members of the Bridge maintained an emphasis on anti-academic art, art that resisted the classical norms. While the artists of the Bridge wanted to push boundaries and break away from the mainstream, Bridge artist Kirchner maintained that the female nude should be “the basis of all fine art.”[2] In accordance with this idea, the Bridge members all focused on painting a nude that was different from traditional Greco-Roman ideals. Rather, they painted the nude of the non-Western woman, considering her to be closer to nature and holding elusive spirituality. They painted her in vivid colors and jagged angles, rather than in idealistic proportions. They resisted realism in their work as an attempt to rebel against civilized urban society.

The artists of the Bridge also used the nude to represent a sort of Arcadia, making the figure a characteristic of a greater utopia. Antliff and Leighten describe the idea of primitivism as “appropriating the supposed simplicity and authenticity [of peoples deemed primitive] to the project of transforming Western art.”[3] The Bridge artists did this in their rendering of the nude, which they conveyed with through simplified form, although each artist worked in different ways.

Pechstein’s nude in The Indian and Woman is set in a contrived studio scene. Müller paints the nude in nature in his Three Girls in a Wood. Kirchner presents the nude as sculpture made of wood, to mirror a natural material, in Standing Nude, showing that he was looking to Oceanic and African art as models. All of these works, however, emphasize the theme of the primitivist nude and show this shared theme of the Bridge. The composition of each piece is well thought out, yet they maintain almost a crude, spontaneous element to them. This is because the artists felt that the people from outside of Europe and North America were raw. They were ostensibly closer to nature, they did not wear much clothing, and they seemed much different than Europeans, as they were apparently untouched by city life.

Despite their very different personalities, all of the Bridge artists were enticed by non-Western cultures, because they wanted a return to nature and simplicity during the urbanization of Germany. They resented the Academy and sought innovative practices in the rendering of art. Müller, Pechstein, and Kirchner all use diverse techniques and mediums, but they employ the general characteristics attributed to their ideas of the primitivist nude. Each of the forms is simplified and has a coarse quality to it, unlike the Greco-Roman classical nude, which was formerly the quintessential nude in art. The artists of the Bridge sought to create novel ideas in the European art world, while also exploring a world to which they wanted access, but could never have.

[1] Ian Buruma, "The Bridge to a Dangerous Future,” The New York Review (2015) n.p, accessedMay 1, 2015. Web.

[2] Jill Lloyd, German Expressionism: Primitivism and Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press), 1991.

[3] Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, "Primitive." In Critical Terms for Art History, edited by Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 217.

The Printing House of the Family Blaeu

The Printing House of the Family Blaeu: 17th Century Cartographic Printing from the Netherlands.

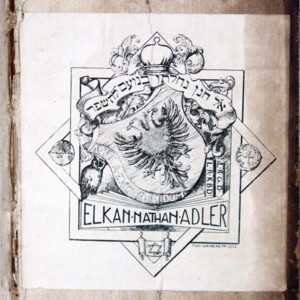

The Rare Books of the Shimeon Brisman Collection in Jewish Studies

The Shimeon Brisman Collection in Jewish Studies was purchased by Washington University in 1972 from Shimeon Brisman, a Judaica bibliographer at the UCLA library and an expert in Hebrew bibliography. Approximately one fourth of the Brisman Collection is bibliography, including hundreds of catalogues from nineteenth and early twentieth century European bookshops. The collection also includes a large number of rabbinical commentaries, responsa, and liturgical literature—many of which came from the libraries of prominent rabbis—as well as a substantial number of nineteenth century sermons from England and Germany. In addition, the collection includes an impressive array of early printed works and rare books. All of these items capture Jewish history, culture, and thought and serve as a valuable resource for modern day scholars.

The Shimeon Brisman Collection in Jewish Studies was purchased by Washington University in 1972 from Shimeon Brisman, a Judaica bibliographer at the UCLA library and an expert in Hebrew bibliography. Approximately one fourth of the Brisman Collection is bibliography, including hundreds of catalogues from nineteenth and early twentieth century European bookshops. The collection also includes a large number of rabbinical commentaries, responsa, and liturgical literature—many of which came from the libraries of prominent rabbis—as well as a substantial number of nineteenth century sermons from England and Germany. In addition, the collection includes an impressive array of early printed works and rare books. All of these items capture Jewish history, culture, and thought and serve as a valuable resource for modern day scholars.

Featured here are some of the highlights of the approximately 750 rare books of the Shimeon Brisman collection.

We’d love to know if you have additional information about any of the entries on this website. If so, please contact us to share your story.

Special Collections Department

Washington University in St. Louis

Above: Hamishah Humshe Torah (Pentateuch). Printed in Amsterdam by David de Kastro Tartas in 1666.