Digitizing Hope Mirrlees's Paris

Like so many modernist texts, Hope Mirrlees’s Paris: A Poem is not easy to read. Written during 1919 and published in a print run of 175 copies by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1920, Paris is a formally experimental depiction of a woman’s movement across the postwar City of Lights over the course of a single day. Set during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, it is a poem that requires us to see and hear as we read: it is full of period-specific imagery (advertisements, street signs, posters in a Metro station), sounds (bits of conversation, several bars of music), and architectural references, and several sections incorporate the techniques of concrete poetry.[1] Virginia Woolf, who typeset the poem, called it “obscure, indecent and brilliant.”[2] And the late Julia Briggs, who introduced and provided a foundational set of scholarly annotations to the poem in Bonnie Kime Scott’s Gender in Modernism (2007), declared it a “lost modernist masterpiece.”[3] Since the publication of Briggs’s annotations and, more recently, Sandeep Parmar’s edition of Mirrlees’s Collected Poems (2011), scholarly attention to Mirrlees has grown steadily. Yet our ability to teach Mirrlees in courses on modernist studies remains somewhat limited: nearly everything she wrote is out of print, and unlike, say, T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, to which Paris is frequently compared and which was repackaged as a digital edition via Touch Press in 2011, there has not yet appeared “an app for that” that would make Mirrlees’s poem seem approachable—even, if you’ll forgive us, relatable—to contemporary students. Four years ago, with the explicit understanding that adaptation can enable more attentive reading practices in our classrooms, we set out to change that. Working with a team of faculty, staff, and students in the Humanities Digital Workshop at Washington University in St. Louis, we began the process of creating a digital edition of Mirrlees’s Paris—a project that, like the poem itself, has turned out to be vastly more complicated than we had initially thought.

We want to share the most interesting of these complications in order to suggest that the process of re-mediating Paris has fundamentally changed the way we read it. In our experience, moving Paris from the page to the screen has required us to learn to read and see the poem. Reading the text of the poem has become, for us, only one way to think about it; in part because our interdisciplinary team initially included Jaleen Grove, a historian of illustration and graphic design, we were immediately prompted to see every page as an image. Attending more carefully to the poem’s visual design, seeing the white space on every page as meaningful rather than empty, in turn forced us to see Paris as the result of a serious collaboration between the poet and her printer: Hope Mirrlees, “modernism’s lost hope,” and Virginia Woolf, “icon, celebrity, star.”[5] How does re-centering this collaboration help us to understand the poem and its burgeoning significance within feminist modernist studies? And what might attention to this collaboration between the lost and the luminary prevent us from seeing, reading, teaching ourselves?

Let’s back up. In order to create a digital edition of Paris we had to figure out how to translate text on a page into text on a screen. Given the widespread availability of applicable online models, this task initially seemed straightforward.[6] However, we quickly realized that how you translate a text to digital media, and what aspects of it you choose to translate, are complicated questions. When you read texts through big online libraries like HathiTrust or The Internet Archive, you often have the choice between a PDF facsimile of the work and a plain text version.[7] Underlying the plain text is usually an XML file, which is a marked up version of the text in which structural elements and important features are tagged. This dual system—a facsimile of the original edition, along with an XML transcription that appears as continuous, unformatted text—is very common, and for many, moving between these two formats has become routine. This system allows you to interact with a work in two quite different ways: the facsimile provides a sense of its original format and visual effect, while the text allows you to search, copy, and manipulate the words.

We wanted to make both kinds of interaction possible in our edition, but we quickly realized that we could not simply follow this model with Paris. Scanning the pages of the book was easy enough, but translating the poem into digital text presented problems. As we mentioned earlier, Paris is visually and typographically complex, incorporating graphic elements, musical notation, and lots of variant spacing. If we tried to represent the poem without those aspects of it, we would lose much of its effect and meaning. However, if we simply included scans of the book, we would, in some sense, be failing to represent it as text; we would just have turned it into a series of images. How could we represent the visual effect of the text in XML?

Unfortunately, the immediate answer seemed to be… we couldn’t. While XML is an entirely text-based markup language, users have to choose whether they are representing their source materials as facsimiles or texts. The use of XML for archival and academic purposes is guided by the Text Encoding Initiative: a group of scholars who have worked to create consistent standards for marking up texts. There are TEI guidelines for the encoding of verse, as well as guidelines for recording pages as visual surfaces, but those options represent two different ways of organizing—or, for the purposes of our work, seeing—a piece, and they cannot be incorporated into one another. If a text is recorded as verse, the primary unit of organization is the poetic line, and those lines are usually gathered into line groups representing individual stanzas or verse paragraphs. Paris resists this kind of organization because, due to its complex inter-line spacing, there is often no way to know where a line group should start or end.[8] If a text is recorded as a series of visual surfaces, on the other hand, the facsimile element is required, and it is explicitly non-textual.[9] Thus we were again left with the same problem: should we record Paris as a poem, or a series of images? Compounding this problem was the fact that facsimile transcriptions are most often used in manuscript studies, and our most robust systems for recording visual information about texts in XML are designed to describe handwritten, rather than printed, material. If we chose to do a facsimile transcription of the text, we would not only be shifting the way we thought about and organized our edition of the poem, but we would be adapting the conventions of manuscript studies to the representation of a 20th-century printed text.

The decision about whether to interpret Paris as text or as image has a direct bearing on the representation of Paris as a collaboration. As the only two extant page proofs demonstrate, Mirrlees was extremely particular about how her poem was laid out. But she and Woolf were communicating only via letters, and Woolf was the one who controlled where each character was printed on the page. At the time, Woolf was still new to typesetting; Paris was only Hogarth’s fifth publication. As an amateur publisher and fellow writer, her efforts to translate Mirrlees’s words onto the printed page involved a significant amount of improvisation and ingenuity. Without distracting attention from Mirrlees’s significance as a poet, it is clear that Woolf’s work as typesetter was creative labor that, in some sense, was constitutive of the work not just as a book but as a poem.

This focus on Paris as a collaboration put more pressure on our decision about how to record the work in XML. If we adhered to the standards for recording verse, that seemed to privilege Mirrlees’s work as the writer of the poem. However, if we created a facsimile transcription, that would shift the focus to the decisions Woolf made about the layout of the printed text. Either way, we would lose important aspects of the piece. We were stuck. We considered making facsimile and textual transcriptions of the poem, and even set up the XML structure for both. We also considered letting go of some of the visual information we had collected about the text. But as we continued to work on the project, the question of why these two ways of representing Paris had to be so incompatible kept coming up. After all, the visual and the textual aspects of the piece had coexisted in the original book, and all we were trying to do was recreate it in digital form.

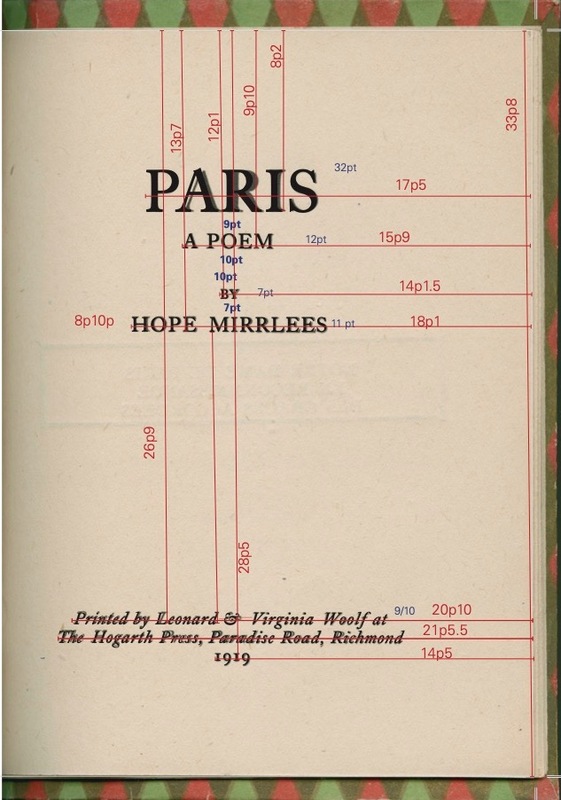

Ultimately, what helped us to solve this problem was a return to the methods that Woolf herself had used when publishing Paris. Woolf printed the book on a small press in her dining room, and all she had to work with when creating the layout for each page were pieces of moveable type that, when inked, made impressions on rectangular surfaces. When we looked at the pages with letterpress printing techniques in mind, it became clear that it was something we could not see that made the complicated layout of the book possible. In letterpress-printed text, white space is created through the insertion of individual pieces of spacing material. These blocks of metal function just like regular type; however, since they are not type-high (that is, not as tall as the other pieces of type), they do not make a mark on the page. Wherever Woolf wanted to create spaces in Mirrlees’s poem, she had to insert spacing material: at the beginning and end of each line, but also within and between lines. In order to copy her layout while preserving the poem as text, we would have to insert individual blocks of spacing material in our edition as well.

Within XML there is a space element which defines white space based on a dimension and measurement (in the user’s chosen units). It also allows for the specification of space “types,” which are categories of spaces that can later be grouped and formatted the same way. We decided to define different types of spaces that corresponded to the kinds of spacing material that would have been available in a standard type case around the time that Woolf was printing. Our categories were: leading, for vertical space between lines; left alignment, for spacing inserted before the first character in each line; character, for extra spaces inserted between letters or before punctuation marks; internal, for spaces between words; and marginal, for vertical spacing inserted before the first printed line or after the last printed line on each page. In letterpress printing, measurements of margins and vertical space are usually given in points (a unit representing 1/72nd of an inch), while measurements of horizontal line spacing are given in different typographic units: ems, ens, quarters, etc. This scale is relative to the size of type being used, where an em is the same width as the letter “m,” an en is half of an em, a quarter is half of an en, etc. Each of these units corresponds to a different piece of type that Woolf could have selected in order to create space within the lines of the poem.

It is important to remember that these pieces of spacing material were very small. When Woolf began printing, she only had one set of type (that she bought used), and it roughly corresponds to what we would now label as a 9-point font. This means that in her typecase, em spaces would have been 9 pts, or 1/8th of an inch, while ens would have been 1/16th of an inch, and so on. The smallest spacing materials in a case are brasses and coppers, which are so thin that they have to be made from different metal. Brasses are one point, and coppers are a half of a point, meaning they correspond to 1/72nd and 1/144th of an inch respectively. Given the very small scale on which Woolf was working when printing Paris,we had to decide how fine-grained we wanted our measurements to be and what level of detail we would include in our digital version of the text.

When we first conceived of the Paris project one of our explicit aims was to take robust digital resources and apply them to a focused, small-scale project. Can digital tools help us read closely as well as distantly? Often digital humanities work is associated with large corpora, quantitative analysis, and the application of machine processes on a broad scale. In marked contrast, we wanted to use digital tools to thoroughly explore one very small book. But now we were left with the problem of figuring out what level of detail it was meaningful to record. How much difference would a tiny fraction of an inch make in someone’s experience of reading the text? Should we try to create a version that captured each piece of metal Woolf placed in her composing stick? Should we represent the work according to the typographic measurements used in England in her time, or should we use modern measurements? How small was too small—how close is too close—in terms of what we tried to read, see, and translate about the text?

Again, returning to the physical processes of letterpress printing helped us make a decision. The blocks of type used to create white space don’t make marks on the page, so if we had inserted space elements corresponding to each of the different typographic units that made up a space we would have been implicitly claiming more than we could know. Thus, rather than create a bunch of separate space tags representing different kinds of spacing material, we decided to convert all of our measurements to modern points. Unlike the em-based scale, which is relative to the font size being used, points are consistent, and they are recognizable to all standard web browsers. In our XML file, measurements for each line and any variant spacing are rounded to the nearest half point, since that is the smallest spacing material available for letterpress printing. It should be noted that the size of a point has shifted slightly since Woolf’s time, so our claim is not that we are using the same measurements as Woolf, but rather that we are doing our best to accurately represent the spacing in Woolf’s text via modern, non-relative typographic units so that users can interact with Paris as text, but also engage with it in a form that preserves its original layout.

The result of this effort is an XML transcription of Paris that follows the original text as closely possible, but lifts it from the setting of each individual page, allowing it to be presented as continuous text that can be read on a variety of different devices, scaled up and down, copied and pasted, etc. We have created a number of CSS interpretations for the text, which allow users to view the poem in different formats--as unbroken, scrolling text or as text on a page--and also provide options to view scholarly notes by Julia Briggs and contextual images from the period. [10] We hope that this combination of views brings attention to the tremendous amount of unseen, collaborative labor that went into the production of hand-printed, typographically experimental texts like Paris.

These different options for viewing the poem also point to one of the most important ways re-mediation changes how we read now: when we access a text through a computer or other device, we expect to have choices about how we see it. Online, we are usually offered multiple formats for viewing a work (primarily facsimile or text, as we’ve noted above) and, where downloading is an option, multiple file types (PDF, JPEGs, plain text, XML, etc.). But we also have a host of other options that are easily taken for granted. We can zoom in or out on a page, flip from a vertical to a horizontal view on a tablet or phone, resize a browser window, highlight words we’re searching for, copy the text into an entirely different application—the list goes on. By translating Paris to digital media, we are both preserving and expanding the possibilities of the text. Mirrlees’s poem is only available to us because one woman with one set of type and a small handpress chose to collaborate with her to bring her vision and her words to an audience in the form of 175 printed books. Now, by removing the text from its physical format, we have created multiple options for how it can be seen and read by many more people. What do we gain from having so many choices about how we see the materials we read? And what do we lose? Do we have an ongoing responsibility to maintain the original form of a text as we translate it into something new? Or, especially when we consider how best to bring such an “obscure, indecent and brilliant” text into our classrooms, do we have a greater responsibility to move beyond it?

These were questions that we had to keep in mind as we began our edition of Paris and they are issues that we continue to work through today. While functions like zooming in, resizing a window, or searching a page are built into the browsers through which our site will be accessed, and are thus out of our control, there have been so many decisions we’ve had to make—so many aspects of how Paris will be seen that we’ve had to choose—that the digital edition, and the different displays we’ve chosen to offer, also represent our own collaborative labor on the project. The default, scrolling view presents Paris as a poem, a continuous literary work that exists outside of its history as a material text. The page view does the opposite; it represents Paris as a book, with text on a visual surface of particular size and shape. The notes view highlights the recovery efforts surrounding the poem, featuring commentary by Julia Briggs, who reignited interest in the poem. And the images view represents our efforts to make the poem more pedagogically accessible. Underlying all of these views, however, is a single XML document that represents the labor of multiple women who measured, recorded, and encoded data about each line and each space in the book, and who, as graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and untenured faculty members, were working collaboratively in and through various stages of contemporary academic precarity.

The question of how we see the texts we teach is contingent upon human labor, upon who brought it into the world and how. Paris would not look how it does without Mirrlees and Woolf’s long-distance collaborative work. Our digital interpretation of their book would not look how it does if we hadn’t had to navigate different perspectives within our group on what a poem is, what a book is, and what it means to put one or both of those things online. And yet the collaboration, the differing perspectives, the shared work that goes into the creation or translation of a single literary work is what we often fail to see when we’re reading—especially in the case of authors, artists, and craftspeople working from marginalized positions within society. How would our ways of reading change if we really tried to see the work of many different people behind a single text? How might our idea of close reading change if we thought about all the decisions, big and small, that had to be made in order to for the text on our page or screen to exist at all? How might this attention to what we can’t see change our ideas about modernist reading? And how, in our own scholarship and teaching, might we work to make these unseen aspects of a text more visible?

by Melanie Micir and Anna Preus

[2] Virginia Woolf, The Letters of Virginia Woolf, vol. 2, ed. Nigel Nicholson (New York: Harcourt, 1976): 384.

[3] Julia Briggs, “Hope Mirrlees and Continental Modernism,” Gender of Modernism: New Geographies, Complex Intersections, ed. Bonnie Kime Scott (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007): 261.

[5] Julia Briggs, “Modernism’s Lost Hope: Virginia Woolf, Hope Mirrlees, and the Printing of Paris,” Reading Virginia Woolf (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006): 80; Brenda Silver, Virginia Woolf Icon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999): xi.

[6] Two important models for us were The Modernist Journals Project and The Victorian Women Writers Project, which both offer XML transcriptions of printed works. For the Modernist Journals Project see modjourn.org and for The Victorian Women Writers Project see webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/vwwp/welcome.do.

[7] See, for example, the versions of another early Hogarth Press book, Monday or Tuesday, available on HathiTrust (babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo1.ark:/13960/t05x2w944) and The Internet Archive (archive.org/details/cu31924013241066/page/n5).

[8] See, for example, page 11. How would this series of lines be most logically translated into line groups? Would it be based on variations in the vertical spacing? In the horizontal alignment? In typeface?

[9] In the TEI guidelines, the element is defined as containing “a representation of some written source in the form of a set of images rather than as transcribed or encoded text.” See TEI Consortium, eds., “Facsimile,” Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange, last modified July 23, 2018, www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/ref-facsimile.html.

[10] You can move between these formats by selecting different options at the top of the page.