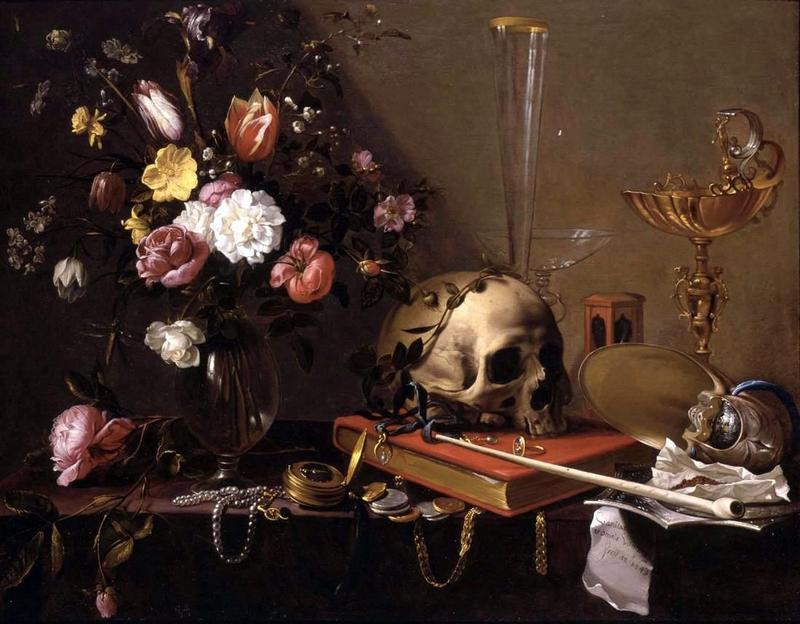

Vanitas Still Life with Flowers and Skull

In his 1642 painting, Vanitas Still Life with Flowers and Skull, Adriaen van Utrecht depicts a multitude of objects, including but not limited to a vase of flowers, a human skull, small gold and silver coins, two glass vases, and a book. In the tradition of still-life painting, these objects have individual meanings all their own. For example, the orange book beneath the skull symbolizes human knowledge. Oftentimes in still-life paintings artists would choose to paint books with their pages open, exposing their content to the viewer as a window into the intellectual realm (note 1). In front of the book, draping softly over the edge of the table, are several gold and silver coins, representations of wealth and status. Another manifestation of the vanitas theme can be found in the timepiece that rests next to the scintillating currency. The cover of this gold clock remains open for the viewer to tell the time and be reminded, once again, about the inevitable passing of time. Although integral to the composition, these symbolic objects do not expose the intrinsic meaning of Utrecht’s still life. Indeed, this painting’s meaning transcends these objects’ symbolism, and it can arguably be found in relationship forged between the bouquet and the skull.

The light radiating from the bouquet of flowers on the left side of the canvas serves as a point of entry into Utrecht’s cluttered, frenetic composition. Of the flower varietals represented in the glass vase, the bright white and yellow flowers are first to captivate the viewer’s attention. Their vibrancy refuses to be ignored, and light seems to glow from the depths of their petals. The flowers found at the base of the glass vase seem to have withered away and fallen from the cohesive bouquet above. One of the rose buds, along with the metal chains and a scrap of paper, hangs limp over the table’s edge, boldly entering the viewer’s space and creating a trompe l’oeil effect. Most of the light in this painting falls on the bouquet and the skull, likely an intentional way for Utrecht to highlight the two most important objects of the painting. Prior to becoming prominent elements within still-life paintings, skulls were oftentimes painted on the back of portraits to remind their owners of life’s brevity (note 2). Placing a flower arrangement directly next to a human skull was surely intentional on the part of the artist, and their proximity forces a dialogue about the relationship between life and death. A craggy, decaying skull in the presence of vibrant, budding flowers seems unsettling at first, and initially the viewer cannot help but wonder how the two could ever be related. A closer look, however, reveals that a profound connection does, indeed, exist between the two ostensibly polar opposites. As the title indicates, Utrecht’s painting is replete with evidence of the theme of vanitas, a theme that tenderly reminds us about the transience of life. Skulls are particularly interesting in that they are no longer part of a living human, nor are they really an inanimate object (note 3). They fall somewhere in the middle, emphasizing their power as symbols of vanitas and reminders to cherish life before death. Utrecht’s work calls the viewer beyond vanitas, however. More than merely symbols of knowledge, life and death, these objects invite the viewer to contemplate the culture of cultivation in which they once existed.

Notes:

note 1. Meijer, Fred G. "Vanitas and Banquet Still Life." The Magic of Things: Still-Life Painting, 1500-1800. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2008. 150. Print.

note 2. Sander, Jochen. The Magic of Things: Still-Life Painting, 1500-1800. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2008. Print.

note 3. Meijer, Fred G. "Vanitas and Banquet Still Life." The Magic of Things: Still-Life Painting, 1500-1800. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2008. 149-158. Print.