European Ambitions

Elite-Light Europeanism

Click the image above for more details about this item;

click here to download a pdf of the score.

St. Louis publishers made an effort to present the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in a cosmopolitan light. The Gaylord Music Library collection includes pieces printed by ten different St. Louis publishers. While some of these pieces are unmistakably popular in content, many of the St. Louis-published works had elite aspirations, reflecting St. Louis’s bid to be taken seriously as a city of international importance.

Louis Conrath’s La Cascade (1904), published by Kunkel Brothers, aims for an elite audience. A sedate cover illustration – an image of the Festival Hall and Cascades, surrounded by a border of oak leaves– emphasizes the elegance of the composition. (This border was also featured on the elite work St. Louis World's Fair March highlighted in Three Musical Styles.) Conrath (1868-1927) calls his work an “impromptu,” referencing the piano music of famous European composers such as Fryderyk Chopin and Franz Schubert. The rapid arpeggiations, representing overflowing cascades of water, and the juxtaposition of triplet and quartolet figures, suggest the pianistic virtuosity of Chopin’s works.

Listen to the European-inspired opening of La Cascade here.

Click the image above for more details about this item;

click here to download a pdf of the score.

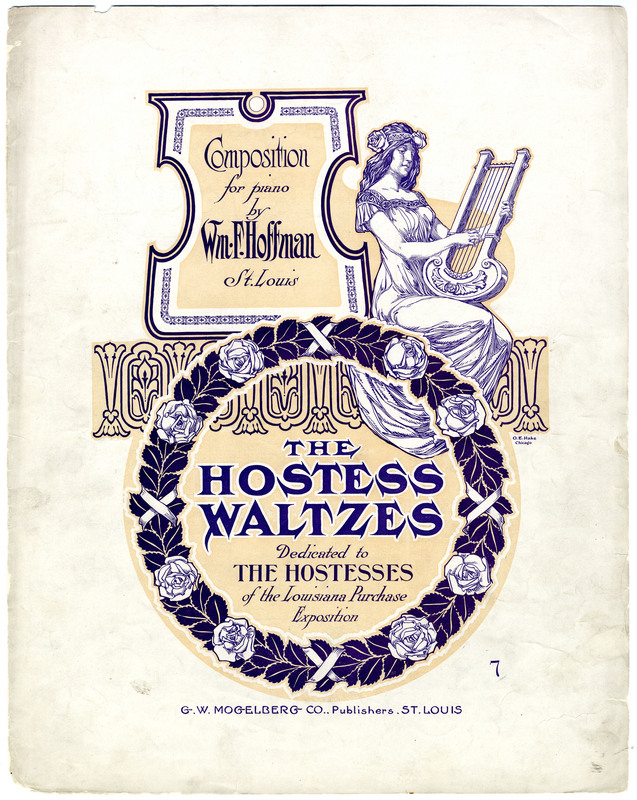

William F. Hoffman's The Hostess Waltzes (published by G. W. Mogelberg in 1904) shows how even light music could tend towards elistism. The cover illustration demonstrates St. Louis’s aspirations to European culture by referencing Greek mythology. It features an updated image of the Grecian muse of the dance, Terpsichore. Traditionally, Terpsichore was shown wearing a laurel wreath and carrying a lyre; here, the laurels are replaced with a wreath of roses. Waltzes were a popular dance form at the turn of the century (think of Johann Strauss's Blue Danube Waltz). Most waltzes, like Hoffman’s and Strauss's, were really a series of shorter waltzes strung together.

The Louisiana Purchase Hostesses Association, to whom the waltzes are dedicated, served as a ladies’ auxiliary to the fair committees. It included women from across the United States, whose names are listed on the back cover.

Click here to listen to an excerpt from The Hostess Waltzes.

Light-Popular Europeanism

Click the image for more details about this item;

click here to view a pdf of the score.

St. Louis publishers and composers drew heavily on European artistic traditions to make their city seem cosmopolitan. Outside of St. Louis, other American publishers used the internationalism of the fair to celebrate European traditions in a lighter, more popular style.

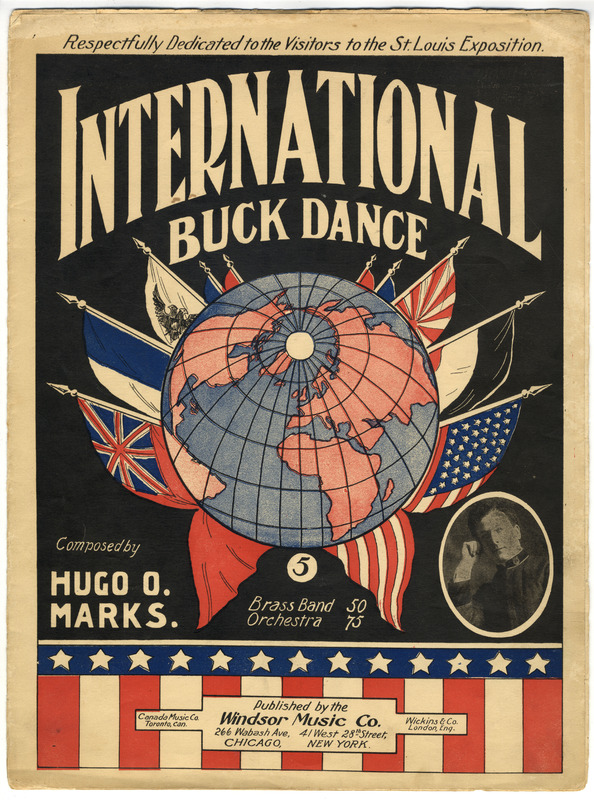

Hugo O. Mark's International Buck Dance (1904), illustrated with a number of national flags, incorporates popular and national songs from across Europe and North America. Buck dancing was a precursor to tap dancing that was often part of minstrel shows.

See how many of these songs you can identify in this recording of the International Buck Dance.

"Knock 'Em Down the Old Kent

Road" (England)

"Die Wacht am Rhein" (Germany)

"The Wearing of the Green" (Ireland)

"La Marseillaise" (France)

"Annie Laurie" (Scotland)

"Dixie" and "Yankee Doodle"

(United States)

Click the image for more details about this item;

click here to download a pdf of the score.

Fred L. Ryder’s St. Louis Exposition March & Two-Step (1904) quotes many of the same national songs. You can listen for them in this recording of Ryder's march.

"La Marseillaise" (France)

"Dixie" (United States)

"Die Wacht am Rhein" (Germany)

"Yankee Doodle" (United States)

"My Country ‘Tis of Thee/God Save the

King" (United States/United

Kingdom).

Identifying a piece as a “march and two-step” was common at the turn of the century. This did not mean that the music started with a march and ended with a two-step, but rather that the music was suitable for both marching and two-stepping. In fact, the two-step craze was partially responsible for the enormous popularity of John Philip Sousa’s marches. Marches, like waltzes and other dance forms, blurred the distinctions between popular and high-art genres.