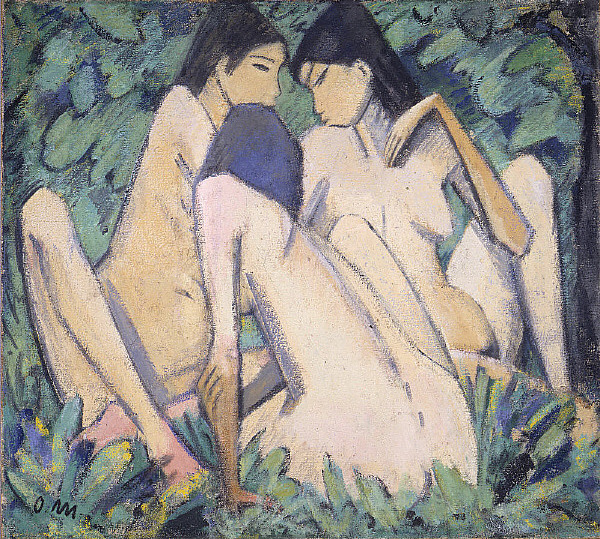

In his large oil and tempera painting Three Girls in a Wood, 1920, Otto Müller uses his studio to re-create a scene that he has learned from other artists, while utilizing his own angular treatment of the primitivist nude. In the painting, he portrays three non-Western nude figures in a studio-contrived scene of nature. In this painting, Müller melds naturalism with expressionism to imagine women from a place he had never been. Like the other artists of the Bridge, Müller attempted to become close to nature himself through the rendering of primitivist art. However, the painting is blatantly artificial, created from imagination. The background is two-dimensional, the foliage has no depth, and the figures are not individualized.

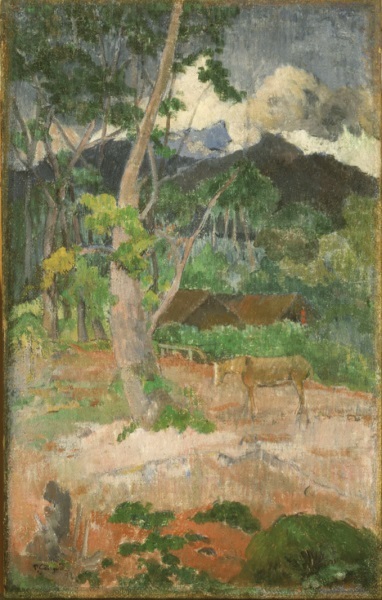

Müller sought to recreate an Arcadia-like paradise, and so he constructed his own in his workshop under the influence of artists like Paul Gauguin, who primarily lived in Polynesia from June of 1891 until his death in 1903. The artists of the Bridge drew from Gauguin’s post-impressionistic style and his rendering of the Polynesian women. Müller especially referenced Gauguin, as he had an interest in depicting the relationship between non-Western cultures and nature but never traveled outside of Europe. Educated as a lithographer in Dresden, Müller moved to Munich in 1898 to pursue painting. Even as he lived in Munich, rapidly undergoing industrialization, Müller maintained a fascination with foreign peoples he perceived as close to nature.

In Three Girls in a Wood, there is a sense of intimacy and privacy about the figures. They are invested in each other, closely touching, their heads angled in towards one another. The audience is merely peering in on this intimate moment. The girls seem to be discussing something secretive and serious, and the viewer is a trespasser on their land. This leads to another premise of the work, the intertwining of the figures and nature. In terms of primitivism, artists were attracted to the idea that women especially were in harmony with each other and with nature. These nude figures represent the desired harmony of nature and humans that Müller wanted to convey. The Bridge Manifesto of 1906 asserts that: “As youth, we carry the future and want to create for ourselves freedom of life and of movement…”[1] The Bridge artists sought to capture this freedom of life through paintings such as Müller’s, in which the nude women talk amidst the trees, very comfortable with one another, paying no attention to anything but the conversation. However, the lack of individualized faces gives the work a sense of artifice. Müller is not creating real portraits of people; he is merely stereotyping a culture and imagining their faces.

In terms of style, Müller’s early works show a more impressionistic style, with small, yet visible, loose brushstrokes. This style began to change in 1910, when Ernst Ludwig Kirchner approached Müller to join his group the Bridge. Under Kirchner’s influence, Müller began to develop a more angular quality to his nude figures, yet he combined this with his loose brushwork. Ten years later in 1920, Müller utilized these aspects of Kirchner’s figures in Three Girls in a Wood, while still showing his respective style as well.[2]

According to Müller expert Tanja Pirsig-Marshall, Müller was very different from the other artists of The Bridge, as he was “highly introverted and did not believe in expounding his ideas in public.”[3] Other Bridge artists such as Pechstein and Kirchner, however, were persistently self-promoting, and also worked to portray their anti-societal values in their art. For example, they used high-key color along with jarring contrasts to show this rebellious emotion. In Three Girls in a Wood, however, Müller uses a simple color palette of greens, beiges, peach hues, and black, adding naturalism to an otherwise loosely expressionist scene. In this way, Müller deviates from the recurring themes seen in the work of the Bridge, defining his own style.

In Three Girls in a Wood, Müller shows his interest in experimenting with different media, painting on burlap instead of canvas. Gauguin could have influenced this choice as well, as he used burlap as a support for Landscape with a Horse, 1899, also in the collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum. For Gauguin, this material was readily available in Tahiti since burlap sacks were primarily used to transport goods for trade.[4] In Müller’s piece, the use of burlap also seems resourceful and conveys a feeling of simplicity and spontaneity, despite the strategized composition of the piece. The medium ties to the subject in that it connects resourcefulness to the subjects and their perceived closeness with nature. In Müller’s painting, the burlap is easily identifiable under the thick oil and tempera, giving it a matte quality that resembles a stucco finish. Some of the paint is peeling from the burlap in places, giving the work a rough texture. This coarse texture gives the aesthetic of rawness, a trait the Bridge artists connected with non-Western cultures.

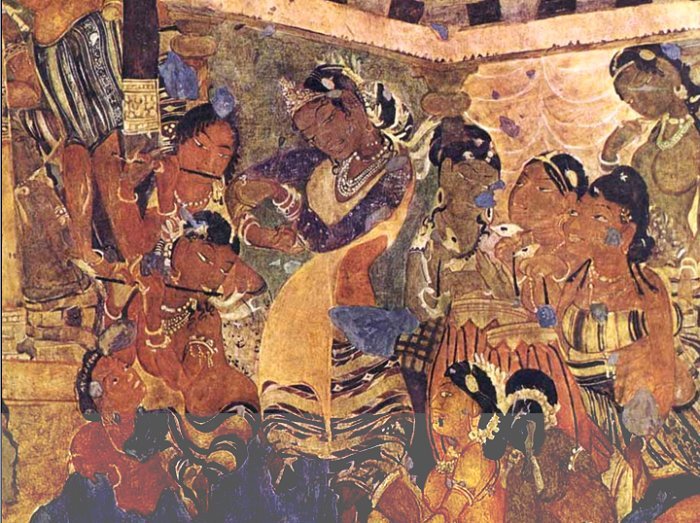

Müller looked to other artists besides Gauguin and their renderings of various natural media as well. In her essay, Pirsig-Marshall discusses Müller’s interest in the Ajanta artists and cave paintings, made with plaster in a technique similar to fresco. Three Girls in a Wood shares pictorial, two-dimensional qualities with these cave paintings. In Müller’s work and the Maha-janaka Jataka tale painted in the Ajanta Cave, the figures are flattened and unaware of the viewer. They interact with each other, but never break the fourth wall to connect with the onlooker. In addition to subject, the matte effect of the oil and tempera on burlap resembles the plaster on the cave. Both materials are natural, symbolizing the resourcefulness of the artist. This painting therefore shows a melding of Ajanta-inspired two-dimensional facets and the influences from Kirchner and other Bridge artists of the twentieth century.[5]

In addition to the material, the brushwork has significance regarding primitivism as well. The three figures’ bodies are very angular with discernible black outlines. The simplicity of the color scheme and line structure could be an allusion to these “primitive” societies that fascinated the Expressionists. While Müller’s figures and foliage have an angular, linear simplicity to them, they are positioned in a way that shows the artist carefully planned the composition. The figures are deliberately seated in a manner that shows three-dimensionality and depth and a relationship between the three. Müller’s preconceived composition gives the visual appearance of one figure being closer to the audience than the other two. The foliage backdrop, however, seems studio-constructed. The plants are like a green-screen, added as an artificial environment to the figures. The figures do not seem to completely blend in, but rather they stand out, away from this backdrop. While Müller is attempting to create a naturalistic scene, there are still elements of the scene that relate to the Bridge’s studio practice. For example, in the Dresden studios, models played the parts of non-Western peoples, and naturalistic backgrounds were created to mimic the relationship between people and nature.

On the periphery of the Bridge, Müller was still a vital part of the group and contributed his own ideas while welcoming the influence of his peers. He shows well thought out composition through his forms and remained very focused on the idea of the primitivist nude throughout his career. Even ten years after the Bridge broke up, Müller experimented with the Bridge’s ideas of expressionism. However, in his work, Müller strives to achieve a closeness to nature, but all he can create is artificial reproduction. He can never fully capture a world he has not experienced. Even as he uses a seemingly resourceful material as his medium, he cannot capture the essence of the people he is trying to emulate.

[1] Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, “Programme of the Brücke,” (1906), Art in Theory, 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, 2nd ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, (Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub, 2003), 65.

[2] David Rodgers, "Müller, Otto," The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Ed. Hugh Brigstocke. Oxford Art Online. (Oxford University Press).

[3] Tanja Prisig-Marshall, "Otto Müller and the Brücke: A Creative Dialogue," In New Perspectives on Brücke Expressionism: Bridging History. Burlington, ed. Christian Weikop. (Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2011), 143.

[4] James K. Boyce, "Jute, Polypropylene, and the Environment: A Study in International Trade and Market Failure." The Bangladesh Development Studies (1995), 49-66.

[5] Tanja Pirsig-Marshall, "Otto Mueller and the Brücke: A Creative Dialogue," In New Perspectives on Brücke Expressionism: Bridging History, ed. Christian Wikop. (Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2011), 150-154.