The Story of Little Black Sambo (1921)

Dublin Core

Title

Description

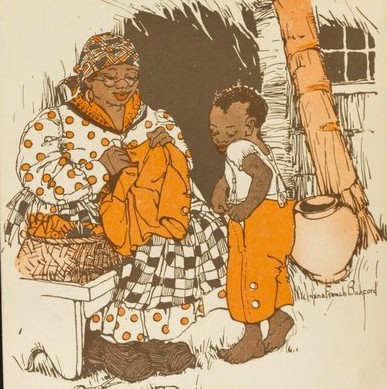

Illustrated seventeen years apart from each other, the two images above represent a similar depiction of the character Black Mumbo in Little Black Sambo. In these images, Black Mumbo is overweight and matronly; in one image she wears a stereotypical headscarf and in the other she wears a hat with big gold hoops. The illustrations’ resemblance to each other is startling given the fact that the original Black Mumbo did not look like anything like the way these images portray her. In fact, the first version of Little Black Sambo, written by Helen Bannerman in 1899, depicted a stereotypical Southern Indian looking family. However as different editions of Little Black Sambo were published throughout the years, illustrators began to re-imagine Black Mumbo’s character as a tribal African mother, as the Mammy and Aunt Jemima image, and as many variations in between.

These different depictions of Black Mumbo represent how in popular culture, like children’s books, black women can only exist as negative representations of black womanhood. This negative representation has a rich and consistent history in society. In Mammy: a Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory, Kimberly Wallace-Sanders writes that “there is virtually no medium that has not paid homage to the mammy in some form or another” (Wallace-Sanders 1). This racist, stereotypical image of the mammy is a staple representation of black women in popular culture still today. The mammy or Aunt Jemima, whose image can be seen on the Aunt Jemima syrup label, is typically a larger, asexual black woman who takes care of a family that is usually white.

Though Black Mumbo cares only for Sambo and not an entire family, she still fits the mammy troupe. In “The Myth of Aunt Jemima: Representations of Race and Region,” Diane Roberts argues that, “white culture divides black bodies, male and female, into useful parts” (21). In this instance Mammy has been taken out of her normal context of the white home, but she is still displayed as taking care of others. In this way, readers preserve their image of her as caretaker and never give her the autonomy to be a woman who is allowed to take care of herself.

Roberts, Diane. The Myth of Aunt Jemima: Representations of Race and Region. London: Routledge, 1994. Print.