For Max Beckmann, war was a learning experience. Though initially a reluctant German Expressionist, Beckmann realized during World War I that the “gestural brushwork, distorted forms, and exaggerated color” of Expressionism were aptly suited to the disturbing and destructive reality of a massive mobilization of military forces across Europe.[1] As the sheer scope of the horror and disaster of the Great War unfolded before him, he wrote to his wife that he was “quite pleased that there is a war. Everything I have done up to now was just an apprenticeship. I am still learning and broadening myself.”[2] (Beckmann would likely have wanted to walk back that opinion after seeing the horrors of World War I). Though he saw the carnage of World War I up close while serving as a medical orderly for the German army, it was not until the outset of World War II that Beckmann, as an avant-garde artist and target of the Nazi regime, came to know the horrors of war and totalitarianism from the perspective of a civilian. His portraits had previously focused on the suffering of others or portraying himself as a self-assured artist. Now they had turned increasingly personal and embattled, as exemplified in the Acrobat on Trapeze, painted in 1940 during his exile in Amsterdam, where, following his flight from Berlin, he lived from 1937-1947.

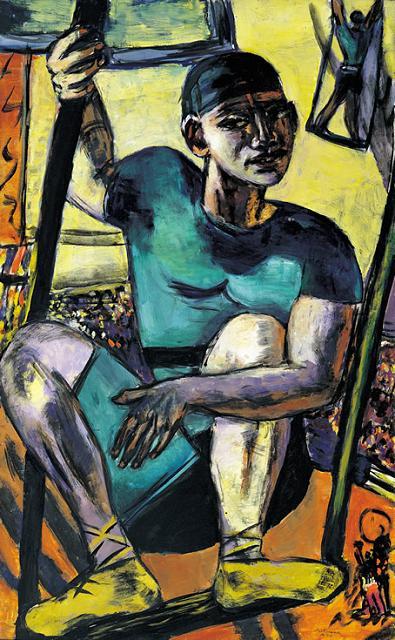

In the painting, the acrobat is on his trapeze high above a crowd in a circus tent. Beckmann painted the tent with thick, bright yellow brushstrokes, but it looks discolored and somewhat garish because the yellow is painted over a dark layer underneath. On the left side of the painting there is a red banner with black squiggly symbols on it, a coded reference to the Nazi swastika flag. Beckmann signed the canvas with an “A” to signify that he had painted it during his time in Amsterdam while the Nazis occupied the city. Seen in this historical context the circus crowd takes on a new meaning: rather than simply an unrelated grouping of individuals at an open public event, they become a faceless, unified crowd of the masses at an event full of nationalistic pageantry and pomp.

The acrobat is suspended in mid-air above the crowd and somehow is crouching on his bar, as opposed to being in the middle of a routine. There is another acrobat in the top left corner of the canvas who is in the midst of performing; he provides the primary movement in the painting. The main acrobat has a strong chest that is accentuated by his tight forest green leotard. His limbs are also muscular, but somewhat deformed, as his right arm wraps unnaturally around the rope of the trapeze. Flaky paint forms a crust on his leg. Significantly, while his body is well illuminated, his face is not.

Given the conditions under which Beckmann was working, it is not a stretch to see an autobiographical component to his work and to view the painting of the acrobat as a form of self-portrait. Beckmann lived under a great deal of stress during his time in Amsterdam, where he moved in 1937 after the Nazis labeled his art, along with that of other avant-garde artists, “degenerate.” Sean Rainbird, the curator of a major Beckmann exhibition in 2003 at the Tate Modern in London, describes Beckmann’s circumstances during his Amsterdam period as those of “a non-national, an exile, and a degenerate artist in an occupied country.” That state of affairs resulted in “sometimes claustrophobic intensity and intimacy” in his painting.[3] The viewer is intimate with the acrobat in Acrobat and Trapeze, seeing the strain on his face and body while the crowd below is too distant and ambiguous for its members to be considered on an individual basis. The acrobat stands distinctly apart, giving the painting a “me against the world,” or, perhaps, “the world against me” air.

The change in Beckmann’s attitude and worldview is especially evident when juxtaposing Acrobat on Trapeze with his earlier paintings of acrobats. Beckmann was fascinated by acrobats, and any other sort of airborne human, because it allowed him to merge the “observed reality” and the “metaphysical reality”—portraying a flying person allowed Beckmann to paint with a “transcendental objectivity.”[4] In Aerial Acrobats (Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent) which Beckmann painted almost a decade earlier, in 1928, the focus is on the relationship of two individuals flying in a hot air balloon. One of the figures, the female, stands in the balloon basket itself, juxtaposed with the male acrobat who hangs out of the basket with his body nearly completely headfirst towards the ground. In Rainbird’s analysis, Beckmann was commenting on the gender dynamics between men and women as well as the metaphysical experience of being suspended in mid-air. Beckmann’s flying acrobats were real-life, familiar subject matter that nonetheless could create a clear bridge to the transcendental, allowing Beckmann to demonstrate its role in settings that would normally be considered quotidian.

When placed in the context of war, in particular the personal experience of the civilian in war, Beckmann’s acrobat becomes a study of human isolation and risk rather than a study of the transcendent nature of the human spirit. Beckmann, as the acrobat, hovers above the crowd but has little control over his circumstances; a strained, tired artist at the mercy of a faceless, totalitarian mob below. The elevated position of the artist, thought to be a privileged post, is now revealed to be a precarious and dangerous.

[1] Starr Figura, German Expressionism: The Graphic Impulse, (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2011), 25.

[2] Max Beckmann, Briefe im Kriege (Munich: Langen-Müller, 1955) cited in Starr Figura, German Expressionism: The Graphic Impulse, (New York: Museum of Modern Art), 2011, 25.

[3] Sean Rainbird, "Max Beckmann in Amsterdam," The Burlington Magazine 149, no. 1255 (2007): 728-29.

[4] Sean Rainbird, "A Dangerous Passion: Max Beckmann's "Aerial Acrobats"" Burlington Magazine 145, no. 1199 (February 2003): 96-101.