Paul Klee engaged in abstraction not merely as an intellectual exercise, but also as a way of representing his highly individualized perspective of humanity and the world around him. He attempted to set himself apart from normal human affairs and engaged with them as a disconnected outsider: “What my art probably lacks is a kind of passionate humanity… In my work I do not belong to the species, but am a cosmic point of reference.”[1] This mindset is present in many of his World War I and pre-Nazi era works. It shows up in particular in his depictions of political figures like Kaiser Wilhelm and Adolf Hitler (prior to the Nazi takeover) as infantile, cubist abstractions.[2] As Klee became ill later in his life and as Hitler began his deadly march across Europe, the all-too-human aspects of Klee’s daily existence forced him to make a stylistic choice. He could continue to use the disjointed abstract forms for which he was famous, or he could use a more realistic style to reflect the very immediate, human trauma he was experiencing. As evidenced by Man of Confusion, Klee chose to use organic abstraction and childlike rendering of the human form to communicate the complex emotions of a dying man trapped on a war-torn continent.

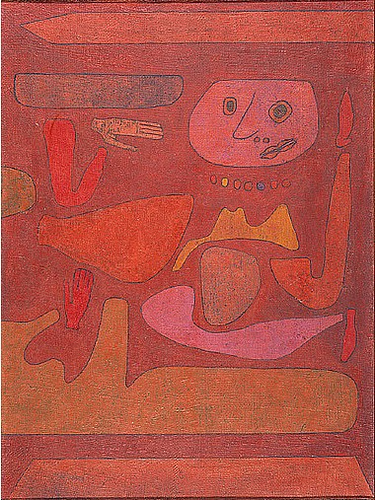

Klee wrote in his “Creative Credo” in 1920 that “elements must produce forms, but without being sacrificed in the process.”[3] That ethos informs the composition of Man of Confusion: the elements float, like amoebas, in an ether of magenta. The forms of a face, arms, hands, and an upper-torso can be readily identified, but they float separately and unconnected. The face is mostly ovular but has a flat top. Two abstract forms frame the body parts, a pencil-like form above and a thicker semi-cylindrical form with a jutting-out section below. This framing has the effect of boxing in the body, implying a sense of seclusion, immobility, and claustrophobia. Though the forms have visible outlines that make them discrete within the ether, they do not stand out due to their colors—all of the elements are some shade of magenta, red, or brownish flesh tones.

When Klee painted Man of Confusion in 1940 he was suffering from an advanced form of scleroderma. The disease affects the connective tissue in muscles and joints, and ultimately leads to the breakdown of organ function because the tissue connecting the organs has been so degraded. Superficially, the disease disfigures the skin in a way that can make it appear severely inflamed and leathery. Klee died from the disease just months after finishing Man of Confusion. Though he was suffering acutely from scleroderma, he maintained the ability to use his hands and continue working, though his output in the final years of his life fluctuated due to the other debilitative effects of the disease. When placed in that context, Man of Confusion becomes a fairly explicit commentary on the artist’s experience coping with the disease. Each of his body parts floats, unconnected, in the ether, just as his actual organs had become unconnected due to the degradation of his connective tissue. The other elements appear bloated and red, which represents the inflammation of his body parts. The overall intentionally childlike rendering, while typical of Klee’s work even before his affliction, can be viewed as a commentary on the childlike helplessness, frustration, and, indeed, confusion of a person suffering from severe rheumatic illness.[4]

Klee’s suffering did not confine itself to his health, however. Though he had lived in Germany throughout his adult life, he felt his safety to be increasingly at risk after the Nazis rose to power in 1933. Klee and his family fled Germany for his native Switzerland in late 1933 after the Nazis labeled his art “degenerate” (the Nazis later featured Klee’s work as part of their infamous “Degenerate Art” exhibition). Though he had technically returned to his home country, Klee viewed himself as living in exile from his community of artists and friends in Germany.[5] The claustrophobic, trapped feeling of the painting can be attributed to both his debilitating illness as well as to the threat posed to him by outside forces that rendered him a prisoner in exile.

Though Klee had fashioned his identity and oeuvre around the notion that he “did not belong to the species” of humanity, the conceptual framing and emotional underpinnings of Man of Confusion belie that notion. Klee was in the midst of dealing with extreme physical, psychological, and existential trauma and his work, while abstract, demonstrates an anguished and sincere engagement with personal and universal human suffering. If his earlier work, in his view, lacked “a kind of passionate humanity,” then Man of Confusion represents a sea change in personal identity and a reckoning by the artist with himself as a flesh-and-blood mortal human being.

[1] Paul Klee, The Diaries of Paul Klee, 1898-1918, ed, Felix Klee (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964), 1008.

[2] Michele Vishny, "Paul Klee and War: A Stance of Aloofness," Gazette Des Beaux-arts 120, no. 1319 (1978): 235.

[3] Paul Klee,"Creative Credo" (1920) reprinted in Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, ed. Herschel B. Chipp (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968), 183.

[4] Hans Suter, "Paul Klee's Illness (Systemic Sclerosis) and Artistic Transfiguration," in Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists, Vol. 3. (Basel: Karger, 2010), 11.

[5] "Paul Klee (1879-1940)." Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History-- Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 1, 2015. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/klee/hd_klee.htm.