James Merrill's Narrative Prose

While he earned his literary reputation on the strength of his many works in verse, James Merrill also carried on a long and intimate relationship with the genre of narrative prose. As a reader, he generally preferred novels to poems, and admired, among others, Dickens, Tolstoy, Cervantes, and Proust. We can find him trying his own hand at the craft of fiction at least as early as 1941, when the Lawrenceville Literary Magazine , a high school publication on whose editorial board he sat, printed his story "Ambition's Debt is Paid." The piece's achievements are modest: "Well written in several parts," a teacher commented, "dialogue stiff at times, and once unduly hysterical." Such faint praise did not deter Merrill from continuing to write stories. By the end of his high school career, a writing instructor would remark on his stories' "social sense [and] sensitive awareness of subtle, nearly occult experience." In particular, the interest in myth, fairy-tale, and legend which informs his juvenile fiction would go on to help shape his approach to poetry.

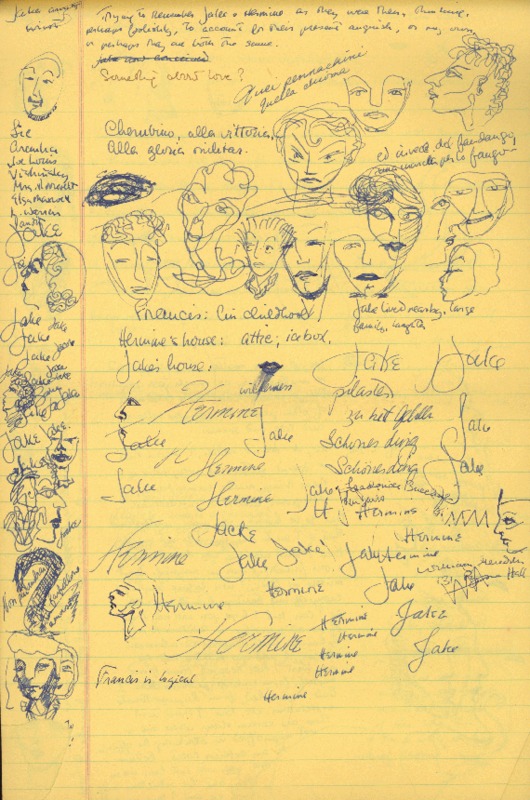

Merrill abandoned his first attempt at writing a novel in 1951, after completing about half of the projected manuscript. In the handwritten draft displayed here, we see some of Merrill's characteristic and fascinating compositional practices; he has doodled the faces of his characters and attempted to create for each one a distinctive signature. At least two characters from this aborted novel — Francis and his ailing father — would reappear in The Seraglio , his first published novel. In his earlier notes, Merrill has imagined Francis' father, a supporting player, as "a bit unclear to me; perhaps a bit like CEM." In The Seraglio , though, the father, renamed Benjamin Tanning, assumes a central role, and resembles Charles Edward Merrill, the author's father, more than "a bit." In fact, the novel is basically a roman à clef, a carefully observed account of the social world in which Merrill moved. First published by Knopf in 1957, it was praised by such taste-makers as Truman Capote and Frank O'Hara, but never found a wide audience.

Even as the publication of collections of verse like The Country of a Thousand Years of Peace established him as heir apparent to the modernist throne of Auden and Stevens, Merrill continued to produce prose fiction. In 1962, he published the short story "The Driver" in Partisan Review . Around the same time, he began work on what he called “The Stonington Novel.” Merrill never finished this piece, but later incorporated elements of it into his trilogy The Changing Light at Sandover . Merrill's finest poetry contains a strong narrative element, and his development of prose drafts into Sandover's verse illuminates the fluidity of genre in his compositional habits.

In 1965, he published The (Diblos) Notebook . This experimental novel, like The Seraglio , featured a narrator with Merrill-like sensibilities. It departed from its predecessor, though, in its exotic setting (the Greek island of the title), and especially in its formal innovations. The narrative assumes the form of a writer's notes towards a novel, and includes some of the fictional novelist's (and perhaps Merrill's) revisions, rewriting, and crossed-out material. The novel was partly inspired by Merrill's visit to the Greek archipelago, and he sent several photographs to his editor for possible use as cover art. Like The Seraglio , this foray into the prose fiction genre met with favorable reviews, but did little to shake his image as a poet, first and foremost.

The early seventies saw the publication of the story "Peru: The Landscape Game" in Prose magazine (1971), and the drafting of another novel. This novel was to feature characters named Sergei Markovich and the Prentisses, but, according to legend, Merrill left the only copy in the back of a cab one night, and it disappeared forever. Rather than attempting to rewrite it, he incorporated it into his poetry. “The Book of Ephraim” concerns, among other things, this "lost novel" and the characters who would have inhabited it. In a fragmentary prose piece displayed here, Merrill speaks of the novel that was to be, the story of "the incarnation and withdrawal of a god." As we can see, by the mid-seventies, his feelings on the narrative prose genre had changed. He has, he confesses here, come to see the "bizarre narrative concoctions" of the nouveau roman as a kind of "orphaned literature." He includes The (Diblos) Notebook in this latter category, and longs for a return to the transcendent simplicity of the enduring myths. Later, Merrill returned to this apology and divided up the lines with a pencil. In an interview with Jean Lunn in Sandscript, Merrill claimed that "This became almost verbatim the opening of ‘Ephraim.’" Again, we can see the close relationship between Merrill's prose and his verse.

James Merrill's greatest narrative triumphs might, in fact, be found in his poetry. Certainly, some critics have come to view his prose fiction as a series of minor digressions from his larger poetic quest. Still, for the interested reader and for the lover of fine prose, they occupy a rich, if narrow, space in the Merrill canon.

Garth Hallberg