Spiritual Archive Beneath the Poetic Artifice: A "Double Vision" of James Merrill's Poetry

Click image for more info on "Spiritual Archive Beneath the Poetic Artifice: A "Double Vision" of James Merrill's Poetry".

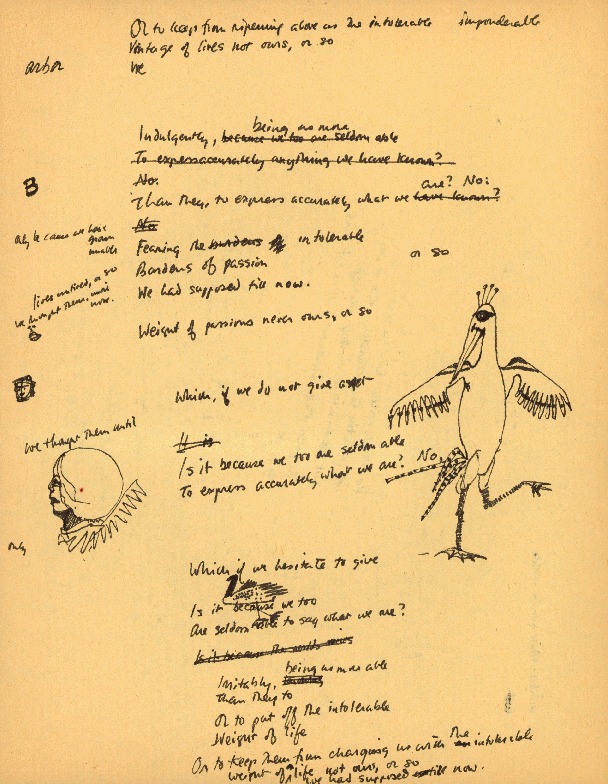

In one of his earliest volumes of poetry, Water Street (1962), James Merrill was already inquiring into what would become one his primary poetic projects: the problem of poetic “double vision.” Poetic double vision, or seeing art as both a representation of reality and as reality itself, would go on to haunt the entirety of Merrill’s poetic canon. Early in his career Merrill demonstrated what Stephen Yenser has called his “dramatic duplicity” — the moment when the poet “turns on himself, or turns, perhaps in a double sense, into himself.” And later in his career, when Merrill began to unveil his occult trilogy, The Changing Light at Sandover , he would reveal even more of his “double self” than he had in any of his previous poems.

The surprise with which

the reading community reacted to Merrill’s first installment of the trilogy, “The Book of Ephraim” from Divine Comedies (1976), is well documented. Prior to “Ephraim” Merrill was known primarily as a poet of well-crafted formalist lyrics, and he had even spoken out against the “monumental” epic tendencies of several of his modernist forebears (specifically Eliot, Pound, and Williams). Like his friend and fellow poet Elizabeth Bishop, Merrill’s early poems were discreet formulations — miniature meditations of a mind attempting to manifest itself in material reality, all the while still doubting this ability to put mind into matter. But “The Book of Ephraim” revealed another, less personally involved, and even less discreet Merrill, a Merrill whose work was beginning to leave the immediate confines of his personal life in favor of the vast, mythological vistas of the spiritual life. And as the materials presented in this exhibition show, this “life” was not a recent discovery, not something that came as a “breakthrough” with Divine Comedies . Rather, it had been moving beneath the surface of Merrill’s work since 1953 — the year of his first attempt at contact with the spirit world.

“The Book of Ephraim” was not initially planned as the beginning of Merrill’s advance into epic poetry, as Merrill thought “Ephraim” complete in itself, and it did not promise to be the beginning of a multi-volume work. But the demands that would be placed upon Merrill by his seemingly newfound “spiritual life” would practically force Merrill into crafting his own spiritual monument in the collection of poems that would come to be called The Changing Light at Sandover . The second volume of Merrill’s trilogy, Mirabell: Books of Number , is in fact the beginning of Merrill’s epic, and it is only after Merrill receives this striking spiritual command that the poem becomes something greater than “The Book of Ephraim”: “UNHEEDFULL ONE 3 OF YOUR YEARES MORE WE WANT WE MUST HAVE / POEMS OF SCIENCE THE WEORK FINISHT IS BUT A PROLOGUE.”

In Mirabell , the epic is, quite literally, invoked in a poetic gesture that is a queer literalization of the epic invocation. In fact, Merrill’s invocation is actually a reversal of formality: Merrill does not invoke the muse, but rather the muse invokes him. The capital letters in the passage quoted above are meant to indicate the part of the text that is dictated by the spirits through the Ouija board. This cast of spiritual speakers includes the four Archangels, various lower spirits, and deceased writers Gertrude Stein, Wallace Stevens, and W. H. Auden, among others.

The seriousness with which Merrill’s spirit communication should be taken is, of course, open to interpretation. But Merrill’s own seriousness regarding these communications seems clear enough; while Merrill occasionally alters the dictated “spirit text,” he is for the most part faithful to the spirit messages as they are recorded in the transcripts from the Ouija sessions. Merrill’s seriousness may also be measured through his correspondence regarding the matter with his mother, which dates back to September, 1955.

In its entirety, the Merrill archive reveals another side of the poet whose persona was urbane, sophisticated, and skeptical. In an early poem Merrill claimed “I’ve tried, Lord knows, / To keep from seeing double,” and perhaps the same can be said on behalf of his poems; he tried to keep them from appearing as doubles, but despite his formal poetic efforts, he could not. Many critics have remarked upon how eerie Merrill’s early work becomes when read by Sandover’s “changing light,” and this eeriness, one feels, is of an individually religious, even supernatural, almost gnostic, caste. Perhaps no one but Merrill knew just how present the “knowing Lord” was in his own life, even though he admitted in an interview as early as 1968: “I must have some kind of awful religious streak just under the surface.” What the Merrill archive offers its viewers is a peek beneath Merrill’s “surface” that reveals a truly strange vision of one of the twentieth century’s most capable formalist poets, one who eventually became one of the most individually apocalyptic poets of any time.

Matthew McClelland and Ryan Shirey