The Creature’s Library

These works are the first ones the Creature encounters when living in isolation near an exiled French family after his creation. They provide the Creature with his unorthodox education, consisting of various subjects including politics, religion, and human suffering. The Creature develops individually, learning that the world extends beyond his experiences in the woods. The texts were chosen, here, in a range of languages to represent the diverse origins of the books that he discovers.

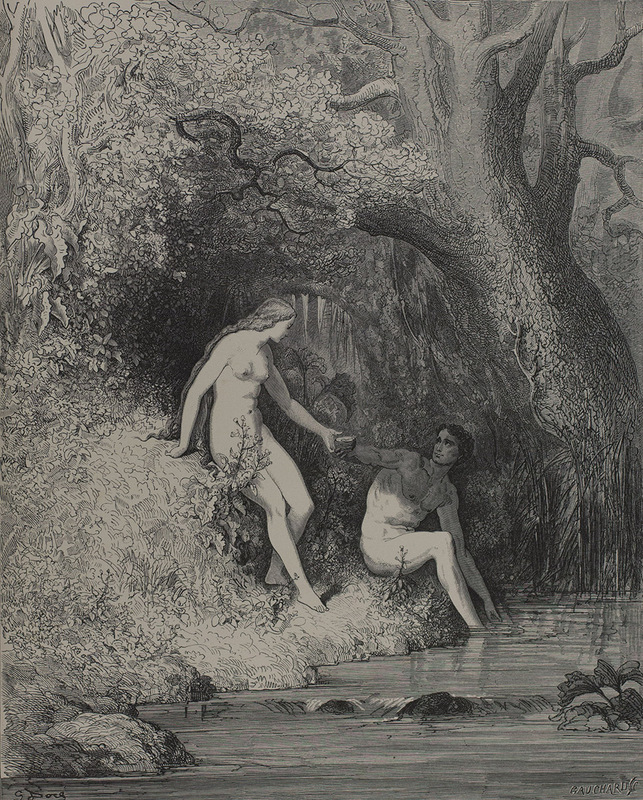

John Milton, Paradise Lost, illustrated by Gustave Doré, edited by Robert Vaughan (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1866)

Paradise Lost

Milton

John Milton published Paradise Lost in 1667 after barely escaping execution for his part in the regicide of Charles I and after becoming almost completely blind. Mary Shelley read Milton’s epic poem, about the genesis and fall of humankind, at least four times in her life, twice before writing Frankenstein. The influence of this poem on Shelley’s work is evident, from the plot to characterizations. Specifically in relation to this section of the exhibit, The Creature’s Library, Paradise Lost plays an intrinsic role in the development of one of the novel’s central figures, Frankenstein’s Creature. The Creature discovers this poem in a satchel in the woods while taking shelter next to a kind, exiled family. The timing of this unearthing is significant, because it is shortly after his traumatic creation, as he begins to develop and mature as a conscious self. Through these texts and overheard conversations, the Creature learns about the sufferings and failures of humanity, but also grows to desire human companionship and love. Paradise Lost, in particular, teaches him a variety of subjects, from persuasive rhetoric to the possibilities of his own creation. He learns from and imitates the innocent characters, Adam and Eve, as well as the sinful, empathetic Satan, as the Creature desires and disrupts paradise. Indeed, the Creature, and Shelley on her title page, quote Milton: “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay / To mould me man?”

-Lisa Brune

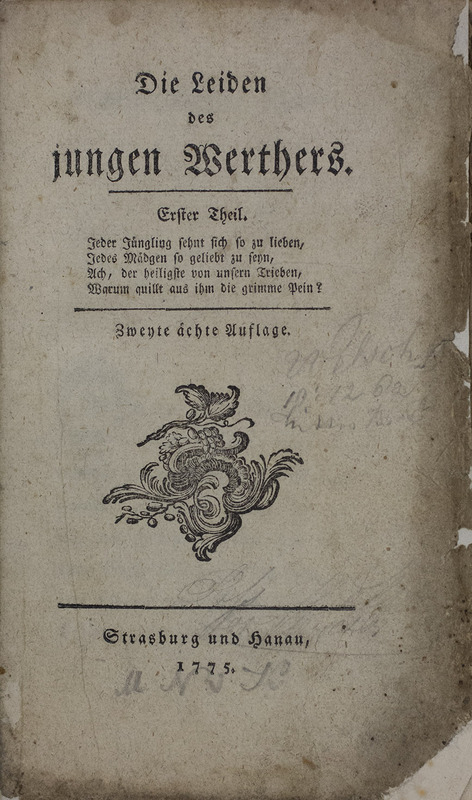

Die Leiden des jungen Werthers

Goethe

Translated into English as The Sorrows of Young Werther, the text was very well known across Western Europe in Mary Shelley’s time, inspiring a following of fans who dressed like Werther and aspired to his extreme sentimental conduct. Shelley read this in 1815, only a year before starting Frankenstein. While Goethe would come to rue the novel for its public reception, Werther was popularly seen as a noble, tragic figure, with his suicide at the end of the novel sadly prompting a number of readers to follow suit. The Creature of Frankenstein, in particular, praises Werther, calling him a “more divine being than I had ever beheld or imagined.” This implies a similar idealization of Werther to that of contemporary readers, and perhaps a similar desire to emulate his character. Werther in all likelihood contributed to the Creature’s expressive eloquence, as he praises the story’s “lofty sentiments and feelings.” It is notable that this is the only book in the Creature’s library that educated him in everyday, human feeling. The language of the text is often similar to the dramatized, intense emotions we see in both Victor Frankenstein and the Creature. Werther’s plight seems to highlight both the Creature’s unfulfilled desire for a mate and Frankenstein’s inability to be with his own love interest. Ultimately, Werther provides the audience with a sympathetic character to ground the Creature’s own temperament in, casting the Creature’s feelings of deep isolation and suffering into an identifiably mundane, human mold.

-Fritzi James

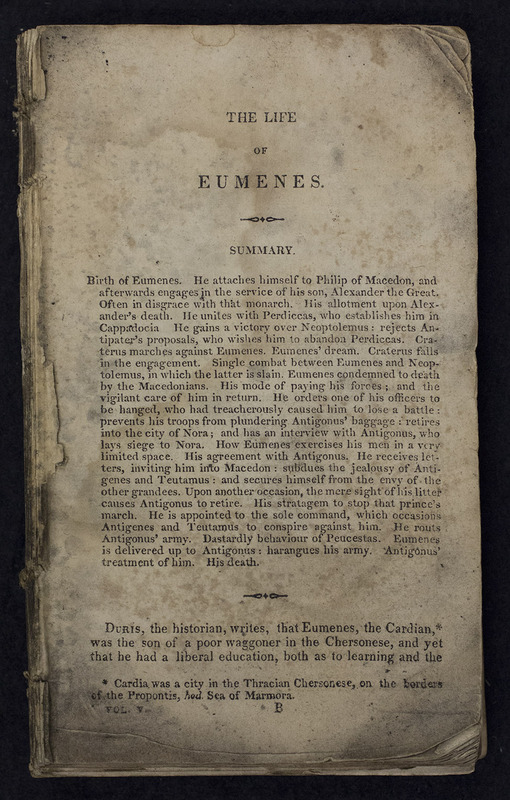

Plutarch’s Lives

Plutarch

Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, often shortened to Plutarch’s Lives, is a history of the Greek and Roman people who contributed greatly to their respective empires. There are 23 pairs of comparisons with 4 stand-alone entries. The work is an amalgamation of history and mythos which illustrates the moral successes and failures of each person, as well as the practical timeline of the Greek and Roman empires. The end result is a comprehensive history which supports Plutarch’s belief that the morality of the ancient Greek heroes is greater than that of their contemporary Roman counterparts. In this way, the text is meant to show the allegorical highs and lows of human tendency. The Creature comes across this work and takes from it the knowledge of the breadth of the world. He sees the triumphs and failures of humanity as well as the geographic diversity which man inhabits. The Creature might have seen parallels between himself and the people in the book, but he does not comment on which figures he identifies with more. Though there are many possible parallels, he is perhaps most similar to Gaius Marius who Plutarch claims was born the son of laborer, and by his own merit rose quickly through the military and then political ranks, ultimately concluding his career as consul of Rome.

-Elliot Crosland

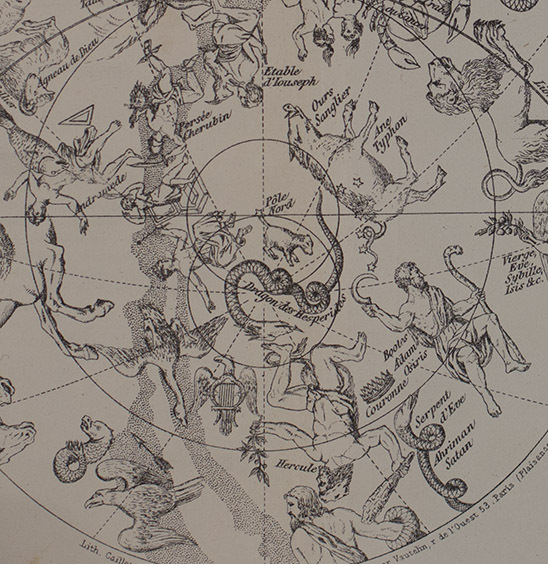

C.F. Volney, Les Ruines: ou, Méditations sur les Révolutions des Empires (Paris: Librairie de la Bibliothèque nationale, 1876)

Les Ruines

Volney

Volney’s Les Ruines is a radical, controversial work grounded in the political climate of the French Revolution. Known as a polymath due to his wide-ranging knowledge of history, philosophy, oriental languages, and politics, Volney offers an expansive depiction of human history. Through descriptions of human greed and brutal acts of violence, the text denounces organized religion and the governments of influential civilizations. Ending with optimism, however, and grounded in a strong commitment to pacifism as well as racial equality, Volney imagines a future defined by peace, a population driven by a commitment to natural law, and scientific advance. Les Ruines is unusual in its presentation, offering a panoramic account of the history of mankind. More specifically, Volney uses a first-person narrator to depict his arguments, incorporating dream sequences, supernatural beings, and other imaginative structures. As depicted here in the 1876 French publication, the work goes so far as to include astrological maps, reflecting the comprehensive nature of Volney’s historical critique. Within Frankenstein, the Creature experiences Les Ruines from afar, listening to a reading of the work to learn the French language. Known for its “declamatory style,” Les Ruines provides an opportunity for the abandoned Creature to begin his solitary education. Furthermore, Volney’s work provides the Creature with a “cursory knowledge of history”. Through such an imaginative, grand portrayal of religion and civilization, Les Ruines offers the Creature with a preliminary understanding of mankind, one that is further complicated by the other three works in his “library.”

-Jack Stephens