Supplemental Texts

These documents widen the sphere of Frankenstein’s production and reveal its evolution beyond the mythic story contest, incorporating it into Mary Shelley’s lifetime of literary achievement. From an early age, she participated in literary and artistic circles which included writers, printers, radicals, and actors from whom she drew inspiration. Letters from Mary and Percy Shelley, and changes made for the 1831 edition, illuminate the wider social context of Frankenstein’s creation.

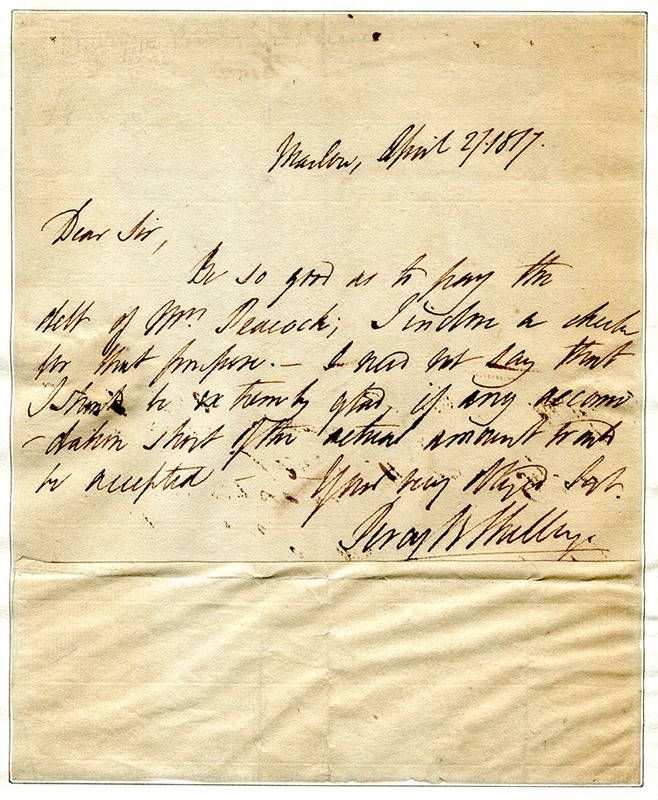

Percy Bysshe Shelley to Richard Hayward

Personal Correspondence

Percy Shelley composed this letter while Mary Shelley was revising Frankenstein from her original short story to its final form as a novel. The Shelleys had returned to England from Switzerland and resided in their house in Great Marlow, Buckinghamshire. There they spent time with neighbors, who included their intellectual circle of Claire Clairmont, Leigh Hunt, and Thomas Love Peacock. Marlow provided a wet, but bucolic, environment for Mary to write and care for their son, William, and future daughter Clara, with whom she was pregnant.

Although the Shelleys had to contend with debts and financial worries, they also helped their friends in need. Percy visited the poor houses in Marlow to provide relief, and in this letter, he requests his solicitor in London to pay the debt of Sarah Love Peacock, the mother of his friend Thomas Peacock. Percy met Peacock in 1812, and Peacock, a classicist, is often seen as encouraging Percy’s love of Greek and Roman literature. The two became friends and intellectual sparring partners, with Peacock often questioning the romantics’ radical “opinions utterly unconducive to any practical result.” Peacock called on the Shelleys at Marlow— ften to Mary’s annoyance—and gave them news from London. In 1818, he provided updates on Frankenstein’s performance: it was “universally known and read” among both critics and Peacock’s reading friends. That same year, he would write Nightmare Abbey, a Gothic satire of his own, gently poking fun at the “morbid visionaries” and “romantic enthusiasts” among his friends.

-Maya St. Clair

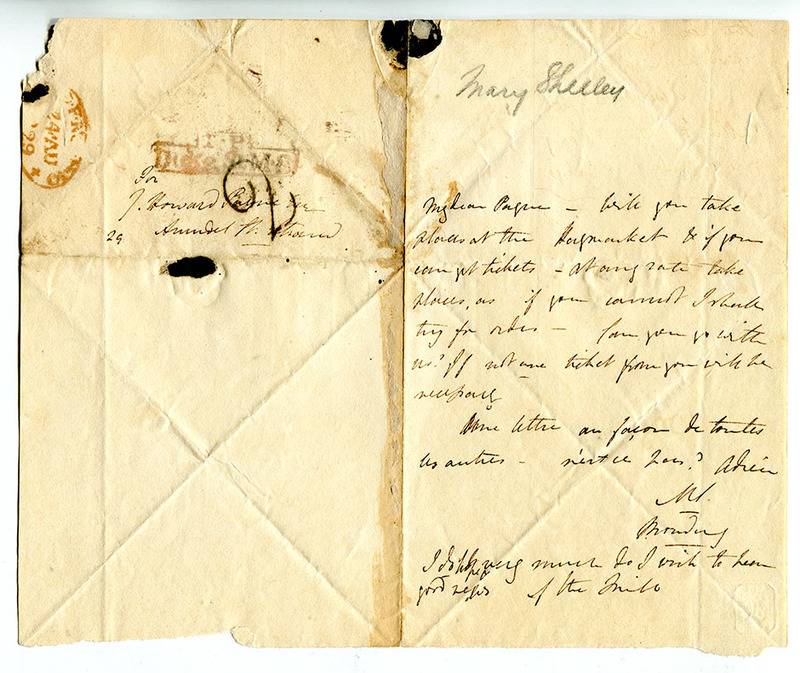

Mary Shelley to Howard Pay

Personal Correspondence

Mary Shelley to Howard Payne, 24 August 1829.

This is one of a collection of letters written by Mary Shelley to Howard Payne between 1827 and 1829. Her husband Percy died in 1822, so these letters give an insight into her relationships with men as a widow. Shelley and Payne met in the mid 1820s and he fell in love with her, proposing marriage in 1826. She refused him, comparing him unfavorably to her first “genius” husband. Letters from the following years reveal an intimate friendship built on shared artistic appreciation. She references books shared between the two and mentions various theater productions, often requesting tickets from Payne (an American actor). The nature of these conversations suggests Shelley’s continuing awareness of the literary and theatrical productions of the day, which is significant since she was in the process of revising Frankenstein. The 1831 edition contains significant changes which arguably shift the novel’s meanings/implications. Her changing perspectives, informed by the intermittent cultural evolutions, receptions of Frankenstein, and the loss of her husband (who played a significant role in the writing of the first edition), were underway at the time of these letters. Aesthetically, they indicate epistolary conventions of the time: her personal seal, creases from folding, her script, postage stamps, ink on the opposite page, etc. Her casual use of French, illustrating her wide-ranging linguistic ability, signals both her familiarity with the language of Frankenstein’s characters/setting as well as the comfortable banality of this correspondence: “une lettre au facon de toutes les autres -n’est-ce pas?”

-Noelle Darling

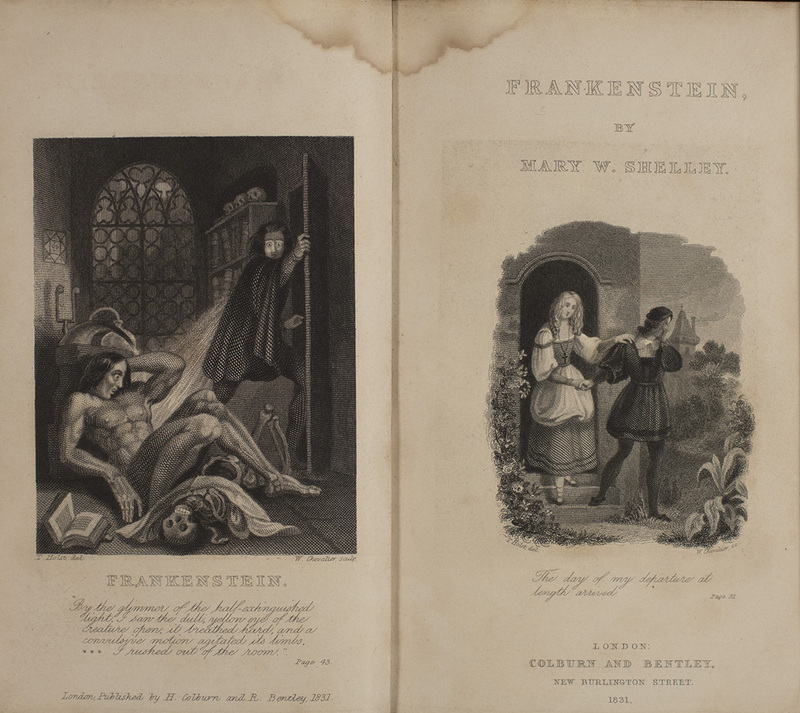

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus (London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1831)

Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus

Mary Shelley

Shelley revised her 1818 novel for the first and only time in preparing the 1831 edition for Bentley’s Standard Novels, where it is bound with Brockden Brown’s American gothic tale Edgar Huntley. While Shelley claimed that her changes were “principally those of style,” critics have noted a philosophical shift as well, in which the disastrous events of the novel are more frequently ascribed to fate than to Victor Frankenstein’s failings. The 1818 version takes a more complicated approach to the question of moral responsibility. Comparing the two offers rich possibilities for literary, historical, and biographical discovery. In her new Introduction, Shelley provides valuable remarks on the novel’s genesis, describing the “waking dream” that inspired her strikingly original tale. In addition, while the novel’s famous central scene does not describe how Victor Frankenstein brought the creature to life, the Introduction for the first time mentions “galvanism.” This recalls broad public fascination with the electrical experiments of Giovanni Aldini in reanimating executed criminals and suggests a mechanism for infusing life.The frontispiece, commissioned for this edition, depicts Victor fleeing from his handiwork, a resonant choice given that Victor’s abandonment of his creature can be seen as the catalyst for subsequent evils. Despite his recumbent position, the startled creature dominates the frame, his power evident in his muscled limbs. A gothic window overlooks contemporary scientific equipment, invoking both the bygone era of alchemy and the dawn of modern laboratory science.

-Dr. Amy Pawl

-Dr. Corinna Treitel