Georges Rouault: Chinois

Georges Rouault, "Chinois," 1939. Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in. Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis, 580:1958.

Georges Rouault’s oil painting Chinois (Figure 1), completed in 1939, illustrates how the artist’s later work typified his style as an artist associated with Fauvism in twentieth-century France. Although Roualt worked in France, he looked to German Expressionism to inform his painting style. Created near the onset of World War II, Chinois encompasses an overall sense of melancholy emblematic of emotions in Europe at this time, in addition to the artist’s own pessimistic outlook on society.

Early in his career, Rouault developed a fascination for the outcasts in society, specifically clowns and prostitutes. The artist transitioned from watercolors to oil paints as his work become more serious and involved, alluding to the hardships inherent in the lives of lower class members like himself. His later oil paintings are distinct in their use of the impasto technique, apparent in the thickness of the paint strokes, and in their resemblance to medieval stained class. Thick layers of paint and solid black lines contribute to a sense of heaviness in Chinois that affects the viewer’s interpretation of the painting’s lone figure. The man sits with his head resting against his hand, conveying a sense of weariness and gloom. His eyes are either closed or in shadow, creating a barrier between viewer and character. Rouault’s somber depiction of the man expresses a detached attitude, reflective of the artist’s perspective on the role of social outsiders, through techniques that encompass both French Fauvism and German Expressionism.

Rouault was born into a poor family in Paris, and struggled to establish himself enough as an artist to be academically trained at the École des Beaux-Arts. His interest in outcasts arose when he encountered a clown outside of the atmosphere of the circus; the artist had the realization that this person, though forced to appear jovial, was in fact sad and dejected, living a life of mediocrity. This event in conjunction with the artist’s battle with a serious illness in 1902 caused Rouault to reevaluate his life’s trajectory, and his work began to reflect a growing concern for human suffering. The artist recorded, “I saw quite clearly that the ‘Clown’ was me, was us, nearly all of us…This rich and glittering costume, it is given to us by life itself, we are all more or less clowns, we all wear a glittering costume.”[i] This epiphany marked the beginning of a series of artworks that served as social critiques emphasizing the contrast between the false appearances and harsh realities of society. Though not directly associated with the motif of clowns, Chinois alludes to this period in Rouault’s life in the way the man is dressed; he appears to be wearing decorative clothing and sports a strange hat, almost giving the impression of a “costume.” The exotic quality of this outfit, in addition to the man’s hidden eyes, contributes to the distance between the viewer and the subject of the painting, creating a sense of mystery.

The feeling of detachment in the painting is further emphasized by Rouault’s references to non-Western cultures. The piece’s title, Chinois, the French word for “Chinese,” indicates the artist’s intent that viewers question the identity of the man, and his costume-like attire is an allusion to a foreign style of dress. Additionally, like other Fauvists and Expressionists, Rouault adopted elements of primitivism in his body of work, and this stylistic component can be seen in the mask-like simplification of the face in this portrait. The amalgamation of cultural influences in Chinois speaks to Rouault’s role as a modern artist; he considered not only the work of his European predecessors and contemporaries but also recognized entirely different societies.

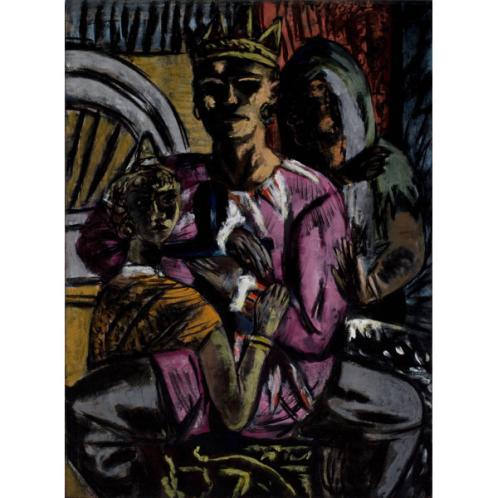

Max Beckmann, "The King," 1937. Oil on canvas, 53 1/8 x 39 3/8 in. Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis, 850:1983.

Rouault came to be known as the link between the French Fauves and the German Expressionists of the 20th century. Although Chinois is often considered Fauvist in terms of style, it adopts a darker palette reflective of an Expressionist approach to color. Renowned artist Henri Matisse, considered the leader of the Fauvist movement in France, is known for conveying joy and harmony through his use of saturated, arbitrary color, and his peers embraced a similar style. Rouault, on the other hand, communicates disharmony through colors that more directly resemble the paintings of German Expressionist Max Beckmann. Experts have debated what category Rouault would fall under, and his style is often described as “Fauvism with dark glasses.”[ii] However, Rouault was not quick to affiliate himself with either movement. Art historian Claude Cernuschi asserts, “Rouault skirted any connection with Expressionism because, like so many artists of his generation, he prized his autonomy and hoped his originality would emerge in sharpest relief.” [iii] This demonstrates his quest for success as an artist independent of any group or association.

Similarities in the styles of Rouault and Beckmann are evident when comparing Chinois (1939) and The King (1937). The two works were painted only two years apart, in the tension-filled times preceding the Second World War, and it is clear how Rouault’s style was shaped by Beckmann’s approach to German Expressionism. Although Beckmann was not directly influenced by the stained glass windows of the Middle Ages in the same way that Rouault was, thick black lines surrounding areas of rich yet dismal color evoke a similar mood by creating a heaviness that alludes to dejection and sadness. In both paintings mystery is heightened by the viewer’s inability to make eye contact with the subject of the portrait. Also, Beckmann dresses himself in kingly attire in order to conceal his status as a rejected artist, which correlates to Rouault’s discontent with the false appearances brought about by “costumes.” Beckmann’s propensity for self-portraiture eventually led to him portraying himself as a clown, correlating with Rouault’s interest in lower-class performers, highlighting his own resentment towards being an exiled artist.[iv] Both Chinois and The King are commentaries on outsiders in society: Beckmann refers to his personal experience as an artist the Nazis regarded as “degenerate,” and Rouault’s composition comments on an overall sense of foreignness.

Georges Rouault’s passion for making known the sufferings of hidden members of society demonstrates why his embracing of elements reminiscent of German Expressionism helped him gain success as an artist. Similar to his Expressionist peers, a somber palette and a determination to convey dark emotions elevates Rouault’s interpretation of this negative aspect of society. It is likely that his clown motif, which developed into a preoccupation with all types of performers, was a precedent for the German theme of performance and circus adopted by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and others of the time. Chinois is an example of how, even after the period during which he focused on clowns, the artist maintained his interest in communicating the effects of human suffering until his death in 1958. Like Kirchner and Beckman, Rouault’s work is indicative of how negativity in twentieth-century Europe shaped not only the development of Expressionism but also the trajectory of modern art.

[i] Franco Mormando, “Of Clowns and Christian Conscience,” America 199, no. 17 (2008): 18.

[ii]Claude Cernuschi, “Georges Rouault and the Rhetoric of Expressionism,” Religion and the Arts 12 (2008): 527

[iii] Cernuschi, “Georges Rouault,” 535.

[iv] Barbara C. Beunger, “Max Beckmann’s Ideologues: Some Forgotten Faces.” The Art Bulletin 71, no. 3 (1989): 467.