Max Beckmann: The King

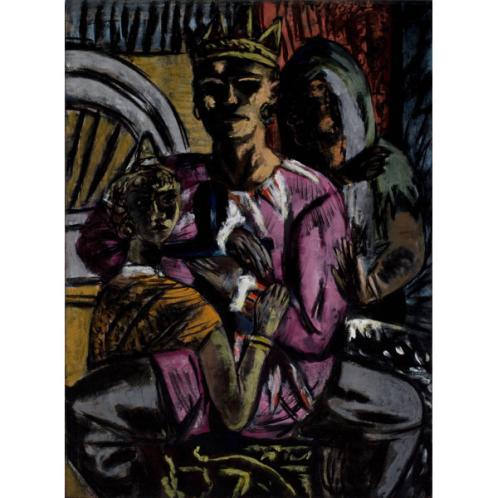

Max Beckmann, "The King," 1937. Oil on canvas, 53 1/8 x 39 3/8. Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis, 850:1983.

Max Beckmann’s The King, 1933-37 (Figure 1) is a self-portrait depicting the artist, with his wife, Mathilde, clinging to him, as an additional figure looms in the background. The work was painted in Germany during the politically tense years preceding the Second World War. Beckmann illustrates himself as a king, crowned and dressed in a royal purple, but the painting is not one of glory or celebration. Thick strokes of black paint permeate the canvas, stressing shadow and darkness in their obstruction of facial features. Disproportionate figures provide a sense of tension and imbalance, and the way the three cling to each other in an anxious manner further highlights the instability generated by an uneven diagonal composition. Abstracted, indecipherable shapes further contribute to the idea of the daunting unknown, a theme in the painting that mirrors the time period in which it was conceived.

Beckmann’s painting is emblematic of the twentieth-century German Expressionist movement in its implementation of personal anecdote as an inspiration for not only theme but also style and technique. The artist’s feelings about current events are apparent in the gloom portrayed through heavy brushwork and deep colors. The King reflects a shift in Beckmann’s attitude toward society; while the painting was displayed in 1933 after he had considered it complete, Beckmann revised the work four years later after leaving Nazi Germany, in order to communicate a renewed perspective on his situation as an artist in exile. The King is therefore representative of subjectivity in Expressionist portraiture that is a manifestation of Beckmann’s evolving opinion on his role as an artist at the time.

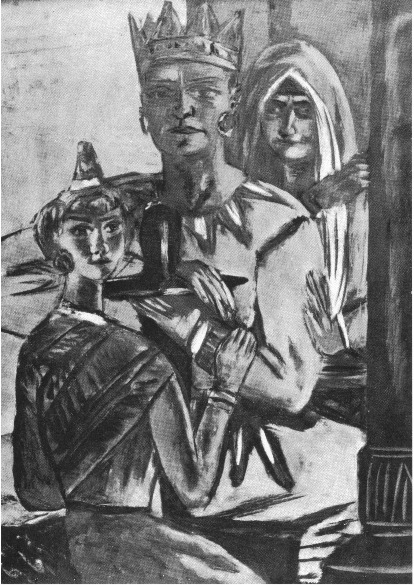

Although he began work on The King in Frankfurt in 1933, Beckmann completed the piece in Berlin after relocating from Frankfurt to Germany’s capital in search of recluse and anonymity. The painting was initially completed in the same year Adolf Hitler was named chancellor, indicative of its being influenced by the country’s heightened political tension. In its first version, The King (Figure 2) was an ominous foreshadowing of the imminent threat that Hitler presented; the mysteriously clothed woman behind Beckmann’s kingly representation holds out a warning hand, while the dainty portrayal of the artist’s wife shields his body with her own, gripping his wrist protectively. Despite the palpable sense of danger, however, Beckmann depicts himself in a prideful manner, and his interpretation of himself as royal expresses his self-regard as an artist.

Max Beckmann, "The King," 1933. Oil on canvas, 53 `/8 x 39 3/8. Current version at the Saint Louis Art Museum.

1937 marked the climax of the Nazi Degenerate Art movement; Hitler condemned all modern art as anti-German or Jewish and therefore modern artists in Germany suffered from a complete loss of support. Almost six hundred of Beckmann’s pieces were removed from German museums, so he and his wife escaped to Amsterdam, where he expressed his dejection in a passionate revision of The King.[i] In its current form, the painting maintains and even amplifies an overall sense of uneasiness and danger, but also indicates a growing vulnerability. While Mathilde’s arm is still placed protectively in front of her husband, the king’s body is more exposed in his open stance. The pillar that once stood defensively in the foreground of the composition is now eliminated, further revealing the body of the now faceless woman who menacingly hovers behind the king’s shoulder. Whereas before the king assertively confronted the viewer with direct eye contact, in the revised version the faces of each figure have withdrawn into dark shadows, intensifying mystery. This amplified uncertainty reflects, as interpreted by art historian Lynette Roth, “a retreat into oneself and into the realm of autonomous art-making that Beckmann had consistently championed.”[ii]

By shrouding his character in black, the artist communicates his desire for anonymity; concealing the king’s face makes the painting less recognizable as a self-portrait and is therefore emblematic of a loss of individuality caused by the impact of the degenerate art movement on the artist’s life. Some have interpreted the blackening of eyes in The King as a representation of blindness, alluding to Beckmann’s desire to punish himself for failing as an artist in his home country.[iii] Unfortunately, the only record of the original painting is in black-and-white photography, limiting analysis of the changes Beckman may have made to the composition regarding color.

Beckmann’s repositioning of the figures in the painting makes the composition feel more crowded and claustrophobic, speaking to how he felt restricted artistically while living in a rapidly imploding society. However, the consistent placement of himself as the king in the center of both the original and the revised compositions exudes a quiet dignity that implies a belief in his own artistic power. In a speech at a London exhibition in 1938, Beckmann declared:

It is, of course, a luxury to create art and, on top of this, to insist on expressing one’s own artistic opinion. Nothing is more luxurious than this. It is a game and a good game, at least for me; one of the few games which make life, difficult and depressing as it is sometimes, a little more interesting.[iv]

The artist’s allusion to luxury parallels the motif of royalty depicted in The King in the way his self-portrait is luxuriously dressed. Beckmann is portraying himself as a privileged individual, despite the hardships he endured. His motivation to create art never wavered, and perhaps even grew in the hopes of conveying his impassioned viewpoint on what was occurring in Europe in the 1930s.

Max Beckmann completed over forty self-portraits in his lifetime, demonstrative of an introspective quality that allowed him to depict the transformations he underwent as an artist in a difficult time period. Self-portraits lend themselves to an in-depth analysis of an artist’s perception of his or herself in a specific moment of time, therefore the genre of self-portraiture in combination with the inherent subjectivity associated with Expressionism allows for a brief yet comprehensive insight into the lives of artists. The King stands as a representation of a period of doubt and despondency in Beckmann’s life; his trepidation regarding moving to a new country away from his home and patrons is evident in the painting’s element of mystery. His proud persistence as an artist, however, remained constant after moving to Paris and then the United States, including the city of Saint Louis, to continue his career.

[i] Lynette Roth, “Manifestations of Exile in the Work of Max Beckmann.” Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik 76, no. 1 (2010): 335.

[ii] Roth, “Manifestations of Exile,” 341.

[iii] M. Therese Southgate, “The King.” Journal of the American Medical Association 279, no. 23 (1998): 1851.

[iv] Max Beckmann, On My Painting (New York: Tate, 2003), 68.