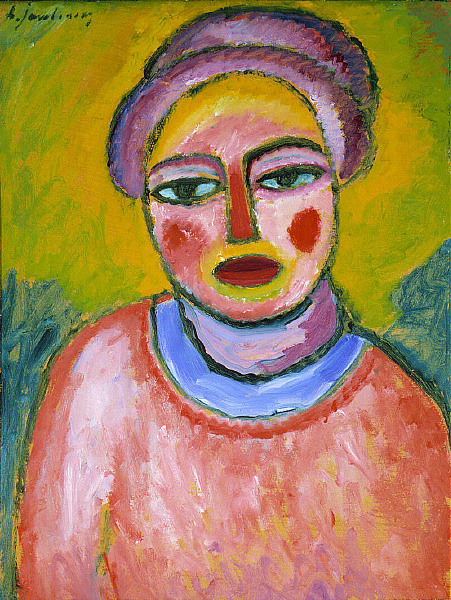

Alexej Jawlensky "Spring"

As a member of Der Blaue Reiter, Alexej von Jawlensky believed that art was a means of expressing spirituality. The act of painting, along with the colors themselves, was thought to provoke primal emotion. However, Jawlensky was a bit of outlier —his limited subject matter of vibrant, bold landscapes and portraits separates his oeuvre from the abstract works of his colleagues, such as Wassily Kadinsky. His portraits, which were increasingly abstracted in his famous Mystical Heads (1917-19) and Saviour’s Faces (1918-20), allude to the Byzantine icons of his Russian childhood. However, his painting of the allegorical figure in Spring, 1912 (Fig. 1), is an homage to Russian Orthodox tradition mixed with references to the aesthetics of African masks. Superimposing the mask on a Madonna-like figure hints that the so-called primitive woman is closer to nature and in tune with herself and the spiritual realm.

Like many of his other works, Spring is animated with vibrant colors and dynamic brushwork. Movement is created in the painting through not only the directional brushwork, but also the layering of paint that is not seamlessly blended. Almost every color of the spectrum is used, with green and yellow most prominent in the background and complimentary reds and purples in the figure. The figure is outlined in green and blue rather than his typical black. Even though parts of the subject are shaded with differing tonalities, the subject reads as two-dimensional due to the bold outline. The only indications of her gender are her hairstyle and her bold, deep red lips. Besides the red lips and pink face, color appears to be arbitrary — her hair is purple and her eyes are a piercing emerald green. Cut off at the torso, the figure’s body is tilted at a different angle than her head, and this asymmetry is also visible in the face. On her right side, the pupil is larger, the blush is less defined, and the eyebrow blurrier. Coupled with drooping eyes, the slight tilt of her face makes the figure seem placid and even somewhat quizzical.

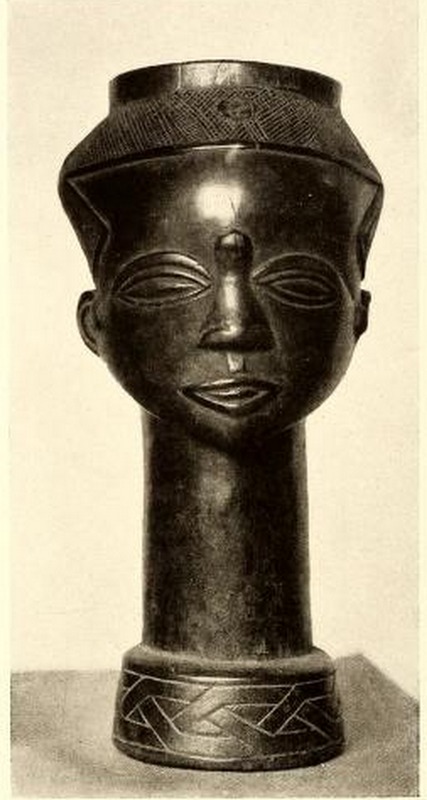

Unlike Otto Müller’s Three Girls in a Wood (c. 1920) or Max Pechstein’s Sunset (1921), Jawlensky depicts the figure with fluid, round shapes — the neck, face, and body appear to be separate forms pieced back together. The only angular form is her rectangular nose, which connects with her prominent, arched eyebrows. This form is reminiscent of African tribal masks that have simplified features and an oval shaped face that Jawlensky could have seen in reproduction or at ethnographic museums in Germany (Fig. 2). In Spring, the large almond eyes, angular nose, and elongated eyebrows of the mask is used in depicting the subject. Due to outline that separates the figure’s face from her neck, it becomes more mask-like and detached from her body. Therefore, the face is not a part of the identity of the woman; instead, her features are borrowed and plastered on, omitting the cultural context of the mask.

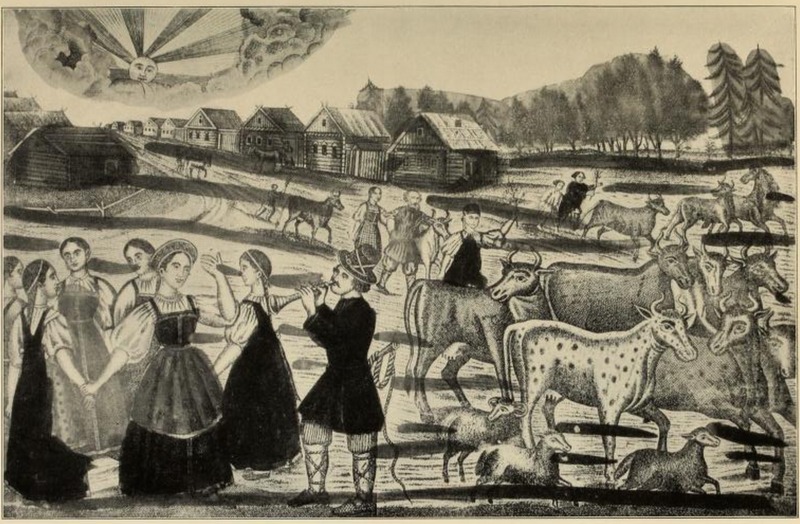

3) Russisches Volksblatt (Russian Broadsheet), reproduced in Der Blaue Reiter. Edited by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc. Munich: R. Piper, 1912. Washington University Libraries, Olin Special Quarto N6868.5 E9 K3 1912 4o.

However, this flatness of form also derives from another one of Jawlensky’s sources, namely Russian folk art and Byzantine icons. As a native of Russia who moved to Munich in 1894, the artist was formally trained in Moscow and familiar with traditional Russian life.[1] Traditional Russian peasant life was source of inspiration to the artists of the Blue Rider. According to Kandinsky, the vibrant, Fauve-like color in folk art was so bold in color that “the image in them becomes dissolved.”[2] Russian folk art, which is rendered with vivid colors, depicted idyllic scenes of Russian countrymen tending to their fields or livestock (Fig. 3). Jawlensky and other members of the group are actively appropriating elements from folk art and including it into their own works. The vividness of color in folk art melds the picture plane into one dimension of flat shapes. Similarly, Byzantine icons (Fig. 4), which are sacred images of the Holy Trinity, Mary, and the saints, are rendered with bold outlines that make the figure and gilded background on one flat plane. The influence of Byzantine icons is strong in Spring, which features the same close cropping of the figure at the torso, in addition to the sense of two-dimensionality.

4) Berlinghiero, Madonna and Child. c. 1230. Tempera on wood, gold ground. 31 5/8 x 211/8 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

To Jawlensky, art was magical — the essence of the sublime. When he was nine years old, he saw his first icon of the Mother of God, and said he had vision afterwards; later, he remarked, “Art is God made visible.”[3] This passion for the spiritual world is reflected in his main choice of subject — the figure. For him, the human, the essence of the world, was the link between nature and heaven. While his later works focus on the face (Fig. 4), the essential form of man, the gender of the figure in Spring embodies the early 20th century idea of women being the “essence” of humankind, as she is the womb of the world.[4]

While publications like the Blue Rider Almanac provided Jawlensky with image of African and Oceanic art and masks, he travelled to the Northern German town of Prerow throughout his life to try and capture the pure universality of humankind. After a summer there in 1911, Jawlensky wrote that he experienced “inner ecstasy” and produced paintings, including Spring, that were full of outbursts of vibrant and almost garish colors.[5] Although he did not travel outside of Germany, the trip was nevertheless an attempt to return to a simple, prelasparian life, which could heighten and strengthen his spiritualty. However, the association of intense outburst of color and emotion with his quasi-religious enlightenment is a primitive concept. Here, in the quaint village of Prerow, Jawlensky saw the village life as a mode of a simpler, so-called primitive life, where human existence revolved around the harvest and the seasons.

The title of this piece, Spring, capitalizes on this idea of rebirth and rejuvenation. By incorporating a female portrait that alludes to icons of Madonna and Child, Jawlensky strengthens the connections between womanhood, a heightened sense of self, and rebirth. Intertwining this ideal with the visual components of the African mask draws connection between them that do not exist — the non-Western woman is not anymore spiritual than a Western woman. The link between the spiritual world and woman falls victim to the stereotype that women, specifically non-Western women, were closer to nature and their inner, spiritual selves. The splicing of the visual elements of an African mask and Mary creates a new figure — the spiritual, so-called Mother Earth. While Jawlensky’s Russian roots informed him of the visual tradition of Byzantine art, his travels to a “simple” Germanic village to find the core spirit of humanity falsely associates spirituality with gender and a return to a simpler life.

Although Jawlensky attempts to connect tradition to modernity with an abstracted form of Mary, he actually fulfills the Western tradition of appropriating non-Western culture’s art for a personal agenda. The splicing of African and Byzantine icons reinforces the notion that non-Western people — specifically women — are closer to a spiritual realm that Jawlensky strove to reach and understand. It may be that art is God made visible. However, appropriating African and folk visual elements due to their supposed connection to nature and a higher power omits their historical context and erases their identity, so that the artist might rediscover his own.

[1] Helmut Friedel and Annegret Hoberg, The Blue Rider in the Lenbachhaus, Munich (Prestel, 2000), 31.

[2] Steven G. Marks, “Abstract Art and the Regeneration of Mankind,” New England Review 24, no. Winter 2003: 53–79, 55.

[3] Clemens Weiler, Jawlensky (Milan: Uffici Editions, 1959), 5.

[4] Lynne Huffer, Maternal Pasts, Feminist Futures: Nostalgia, Ethics, and the Question of Difference (Stanford University Press, 1998), 10.

[5] Ibid., 7.