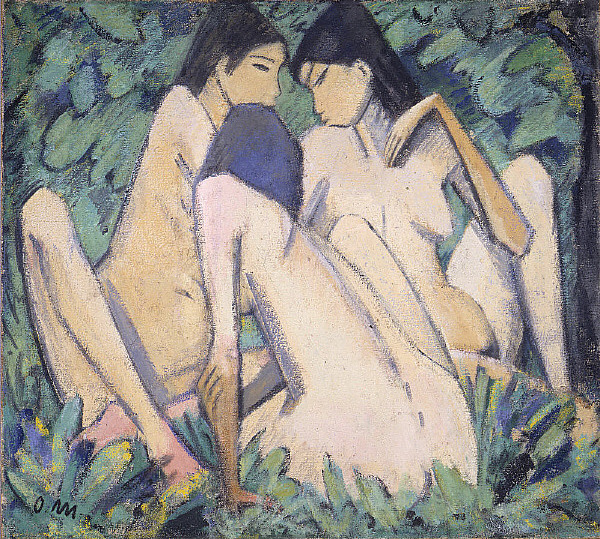

Otto Mueller "Three Girls in a Wood"

1) Otto Müller, Three Girls in a Wood, c. 1920. Oil and tempera on panel. 48 x 53 1/16 in. Saint Louis Art Museum.

Otto Müller, a member of the Die Brücke, had a fiercely unique approach to the nude in nature, while his emphasis on materiality embodied Post-Impressionist ideals. Inspired by collected artifacts and imagined in a studio, Three Girls in a Wood is an artificial combination of non-Western elements in order to create a nonexistent “primitive” world. The studio was an escape from the reality of a modern, bourgeois society, where Bridge artists, including Otto Müller, could create “exotic” settings that expressed a longing for closeness with nature that non-Western cultures ostensibly possessed. While the flat rendering of the nudes is derived from Egyptian and Indian wall paintings, the facial features appear to be quite Asian, with a slender nose bridge, small eyes, thin eyebrows, and jet-black hair. The landscape, composed of a repeating leaf pattern, does not possess distinct features that would pinpoint it to a location; rather, it resembles a tapestry that would have hung in the studios of the Bridge. Although Müller’s arbitrary splicing of non-Western painting styles allows him to create an aesthetically pleasing painting that visually blends human and nature into one plane of burlap, it strips these cultural elements of their context, meaning, and identity.

Painted around 1920, Three Girls in a Wood depicts, as the title suggests, three nude women in a forest setting. Outlined with bold, angular strokes, the women are virtually flat in space with little evidence of three-dimensional shading. Their figures are thin, with limbs protruding at harsh angles. Posed in an intimate circle, their bodies are so close they start to meld into one polygonal form, with one limb of one woman fusing into the torso of another. Eyes, lips, and noses are simplified to singular brushstrokes. Foliage, full of motion and life because of the directional brushstrokes, enclose the perfectly centralized figures into a triangular formation. The color palette is restricted to muted greens, blues, and flesh tones, with small areas of pure yellow in the foliage and pure black in the hair. Due to a mixture of glue tempera and oil on burlap, the entire painting features a thick, matte finish. In combination with the simplified forms of foliage and figure, the subjects read flat and two-dimensional.

The most notable quality about Three Girls in a Wood is its materiality, which references non-Western techniques as a method of returning to humanity’s roots. The glue tempera, which is laid thick on the burlap, is similarly used in Egyptian sarcophagi and Ajanta cave paintings, as well as Medieval and Early Renaissance frescos.[1] This technique allows for a matte surface, which accentuates the materiality of the burlap. The burlap is highly visible even through the thickness of the tempera — the weave periodically creates notable bumps in the surface. The visibility of the materiality burlap through the paint flattens the surface, so that the foliage and the figures appear to be on the same plane. The formal spatial hierarchy is abandoned in favor of recognition of the materiality.

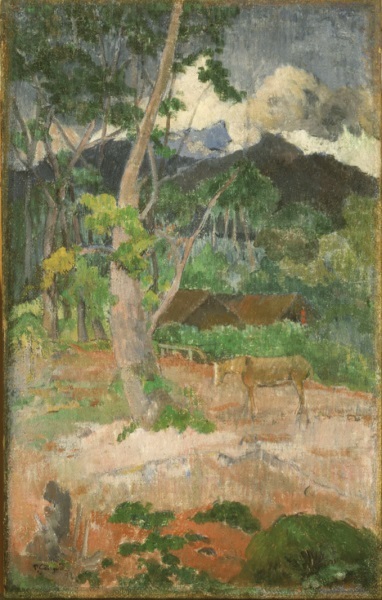

2) Paul Gauguin, Landscape with a Horse, 1899. Oil on burlap. 27 7/8 x 17 ½ in. Saint Louis Art Museum.

The choice of burlap is crucial in understanding Müller’s intentions. While it might have not been a nod to the colonial industry of burlap (among other materials) like that of Paul Gauguin’s Landscape with a Horse 1899 (Figure 2), it shared the sentiment of returning to a natural, less refined state. Both are painted on burlap, an unprocessed fabric of vegetable fibers, as an attempt to find that unprocessed, pure spirit. Many Brücke members, including Müller himself, favored for natural materials or processes. Woodcuts, which produce rough, raw prints, were similarly used to emphasize the materiality of the wood. Burlap is used to achieve a similar effect, as its coarseness of it in highlights the two-dimensionality of Gauguin and Müller’s respective paintings. In both works, the unity between the women and their surroundings is strong — the surface of paint and material is harmonious so that the figures and foliage become one.

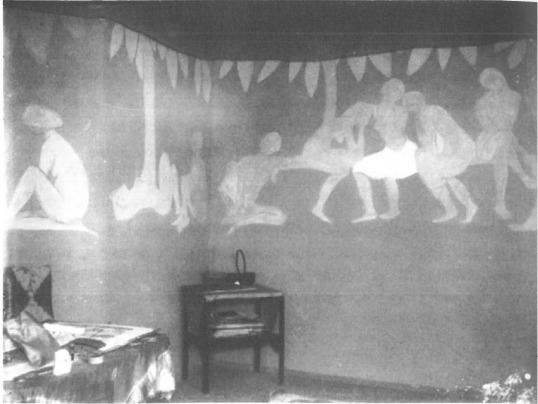

Besides referring to Egyptian and Indian paintings techniques, Otto Müller rebrands their visual interpretations of the human form as his own to support his ideology that non-Western cultures possess the closeness with nature that Western cultures should try and achieve. In Three Girls in a Wood, the flatness, which equates the women and the greenery onto the same plane, fulfills Müller’s goal to “express [his] experience of landscape and human beings with greatest possible simplicity.”[2] The nudes are reduced to their simplest form — outlines. In Müller’s studio, nudes are rendered the same way in friezes and other wall paintings, including ones that he painted directly on the walls of his studio (Figure 3).[3] Besides his travels to Moritzburg in rural Germany, Müller did not leave the city to immerse himself in so-called primitive cultures as had Gauguin or Pechstein. His main source of inspiration was in collected items and the Dresden Ethnographic Museum.[4] Inspired by these collected objects from Oceania and Africa and his knowledge of the Ajanta and Egyptian friezes, the subject are depicted by only an outline, which is also seen in Three Girls in a Wood.

3) Photograph of wall-painting in Otto Mueller’s studio in Mommsenstrasse 60, Berlin-Steglitz, c. 1910, destroyed. [5]

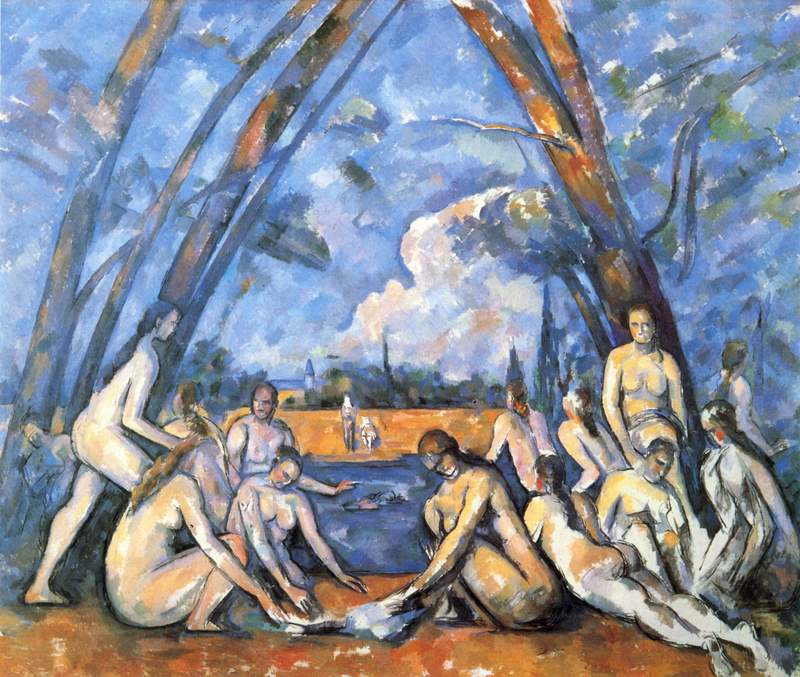

These overgeneralized forms that lack historical context artificialize the setting, forms, and theme of Three Girls in a Wood. The trio of nude girls perfectly balances the composition — almost too perfectly. This artificial pictorial balance is also present in Great Bathers 1898-1906 (Figure 4) by Paul Cézanne. His triangular composition is used in the trees, which frame the nudes away from the man and the buildings, symbols of modernity. However, this composition is imagined, for the trees could not exist like that in reality. Likewise, Müller places the nudes in Three Girls in a Wood in a tight, intimate triangle. Their proximity to each other parallels their closeness to nature. However, this physical proximity does not equal intimacy, as Müller suggests. Because this space, their pose, and their conversation have been fabricated in the studio, it strips the non-Western elements Müller incorporates of their identity. The figures become nothing more than props that Müller can arrange in the confines of his studio to fit his preconceived notions on these “exotic” women and their intimacy with nature.

4) Paul Cézanne, Great Bathers, 1898-1906. Oil on Canvas. 82 7/8 x 98 ¾ in. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Though striking its in bold materiality and compositional structure, Three Girls in a Wood is a culprit of appropriating Asian, Indian, and Egyptian elements to fit Müller’s ideologies of the unity of humanity and nature. The artificiality of its triangular composition and posed women overrides the attempt to return to nature with the use of burlap, which reduce the women onto one plane with the foliage. Non-Western forms are spliced together to create a visually appealing piece but an ultimately artificial primitivist fantasy that is not grounded in reality but within the boundless space of Müller’s imagination.