Browse Exhibits (70 total)

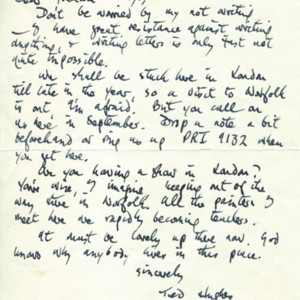

James Merrill - Other Writings

A digital version of an exhibition catalog of other writings by James Merrill in the Special Collections of Washington University, 2001. Text editor: John Hodge. Design and production: Sarah Phares. Production assistance: Whitney Preslar. Web adaptation: Alison Carrick and Jason Stumpf. Essays by members and students of the English Department of Washington University.

Digital exhibit updated in 2014 by Shannon Davis, Joel Minor, Thomas Moore and Teresa Yarber.

James Merrill: Life and Archive

On October 22-23, 2015, Washington University hosted the James Merrill Symposium in the Women's Building and Olin Library. See our YouTube channel for videos of all the sessions, and our Open Scholarship site for further information.

The symposium included an exhibition titled "James Merrill: Life and Archive," in the Olin Library's Ginkgo Room and Grand Staircase Foyer. The exhibition was designed to showcase the James Merrill Papers and the key role they played in the research and writing of Langdon Hammer's biography, James Merrill: Life and Art, published earlier that year.

This digital exhibit includes everything in the physical exhibition as well as additional items, and has references to where in the biography each item is mentioned or referenced. It is hoped the digital exhibit can serve both as a supplement to the biography as well as an introduction in its own right to James Merrill's life and art through his archive at Washington University.

Thus, the exhibit's sections to the right reflect the sections of the book, James Merrill: Life and Art, and the subsections reflect the series in the James Merrill Papers.

For more digitized Merrill materials, see The James Merrill Digital Archive, James Merrill: Other Writings, James Merrill's Poetry Manuscripts and Modern Literature Collection: The first 50 Years.

James Merrill's Poetry Manuscripts

Introduction

“. . . even before the poem is fully drafted, my endless revisions begin

—the one dependable pleasure in the whole process.”

James Merrill interview with Donald Sheehan (Collected Prose, p. 61).

This site provides an introduction and background to selected poems of James Merrill. It features important poems that also have interesting manuscripts, and includes journals and editorial notes. The sections of this site are linked to the paths indicated in the left margin.

Permission to quote from Merrill's work should be made through the Wylie Agency Permissions Website and also through Washington University's Department of Special Collections. If you find any text or image on this site used in violation of copyright, please notify Timothy Materer at Materert@missouri.edu.

For more James Merrill resources at Washington University Libraries, including other digital exhibits, see the James Merrill page on their website.

Joris Hoefnagel: The Nature of Nature Studies

With strong spiritual beliefs at a time of Christian division caused by the Protestant Reformation, Joris Hoefnagel’s illustrations of flora and fauna – especially within his Four Elements – bring nature to the forefront, creating equations between nature and naturalistic study, as well as asking the viewer to question the difference between the human and the natural world (note 1). Every watercolor attempts to close the gap between human and wildlife, and makes each specimen appear spectacular and marvelous; true wonders formed by the tip of Hoefnagel’s brush.

Four Elements was created towards the end of the 16th century; a time where to be considered ‘educated’, one had to be well versed in nature, philosophy, literature, and antiquity. There was no gap between a humanistic and an artistic education. The time also saw the exploration of new lands, which created a constant stream of new information, goods, and services between the new world and Europe. And finally the Protestant Reformation, which began in 1517, heightened religious tension and strengthened many individual’s spiritual views.

Joris Hoefnagel himself was born in 1542 to a father who was a wealthy merchant in Antwerp. Projected to follow in his father’s career footsteps, Joris was schooled in ‘studio humaniora’, which included poetry, drawing, music, and languages. After receiving education from both the Universities of Bourges and Orleans, he traveled a good deal. Most notably, he was in Antwerp for the 1576 sack of the city by Spanish soldiers, which prompted him to move to Venice. In 1577 he took a trip with cosmographer and friend Abraham Ortelius, which ended with Hoefnagel taking a court position with Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria. Hoefnagel worked here until it was required that every court employee sign a Counter-Reformation Credo, to which he didn’t agree and therefore was dismissed in 1591. Following, he worked under Emperor Rudolf II, during which time he illuminated a manuscript by Bocskay, before moving to Frankfurt and then Vienna, where he drew for his Four Elements. His religious experiences, travels, and court circles enabled him to become a highly skilled and well-known artist, specializing in manuscript illuminations and small-form cabinet miniatures, at the head of the still-life tradition (note 2).

Confined to a gold-lined oval on parchment, each specimen within Four Elements is illustrated in a meticulously precise manner as Hoefnagel takes his time to understand the form and occasionally the environment within which the insect or animal lives. Dragonflies perch on a bare page, casting shadows that create a trompe l’eoil effect, while turtles bask in the sun as they rest on sandy shores. The weaving of both an artistic and naturalist approach argues towards Hoefnagel’s expansive knowledge, gained both by directly observing these species as well as exposure via descriptive texts and prints that were being circulated throughout Europe at that time.

This exhibition will explore Hoefnagel’s images as objects of visual pleasure, specificity, accuracy, and as a way to organize information. It will explain how Hoefnagel combines these ideas and creates an ambitious catalogue of animal and insect studies, embodied by Four Elements, as well as how he intermingled art, science, nature, and humanity within each of his watercolors. Hoefnagel blurred the line between the different purposes of images, leaving the reader questioning the difference between themself and the environment. He intertwines the human story with the natural world, and collapses each by constructing parallels within his works.

Notes

note 1. Note that the words “naturalistic study” are used rather than what would traditionally be stated as “science”. This is because what we perceive to be science is so advanced compared to that time – keep in mind that the microscope was invented and used beginning at the end of the 16th century; around the same time that Four Elements was created. From here on, this online exhibit may use “science” and “naturalistic study” interchangeably with the aforementioned understanding. To learn more about how the microscope impacted naturalistic understanding and classification of the time, please reference James Elkins “On Visual Desperation and the Bodies of Protozoa," Representations, No. 40, Special Issue: Seeing Science (Autumn, 1992), pp. 33-56.

note 2 For more complete information about Hoefnagel’s travels, please reference Thea Vignau-Wilberg, “Joris and Jacob Hoefnagel," Archetypa Studiaque Patris Georgi I Hoefnagel II (1592), pp 17-28 or Hendrix, Lee and Thea Vignau-Wilberg “Joris Hoefnagel, the Illuminator," Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta (1992), pp 15-28.

Life in Paris and Berlin in the Early 1900s

Artists living in Paris and Berlin at the beginning of the twentieth century were able to convey their experience of modernity through the visual language of painting. The artists conveyed their fears and hopes in paintings of residents of the city and cityscapes. On canvas, they explored personal experiences, but they also hoped to instigate change through their art.

Disillusionment with city life, a motif explored by many artists in the early twentieth century, reflected their common experiences of urban alienation and political upheaval. During the nineteenth century, the rapid growth of cities in Europe as a result of new technologies and industry greatly changed the way humans lived and interacted. These new conditions of modern life created cultures within Berlin and Paris that rejected traditional notions of simplicity and natural existence. The stark difference between Berlin and Paris between 1900 and 1930 contextualizes the contrast between artists painting the two cities. During that period, Berlin underwent drastic changes in government. More importantly World War I created mass chaos and uncertainty for its citizens. Paris on the other hand grew before and after World War I, and was hailed as the symbol of France’s triumph in both the political and cultural spheres of Europe.[i] By comparing works painted in Berlin and Paris in the early twentieth century that depict modern urban life, we can conclude that artists were able to inject their own perceptions and feelings concerning the experience of modernity.

The three main pieces of this exhibition, Ludwig Meidner’s Burning City, 1913, Ernst Kirchner’s Circus Rider, 1914, and Robert Delaunay’s Eiffel Tower, 1924 depict the cityscape, the urban scene, and the monument, respectively - three key aspects of a city that together demonstrate its whole character. Meidner and Kirchner, living in Berlin, reacted to modernity with criticism of its apparent shallowness that for them suppressed the ideals of humanity and brought out the negative, superficial tendencies of humans. Their depiction of the spaces and the people in urban areas reflected their discontent, as they use skewed perspective and composition as well as careful manipulation of color and brushstroke to transfer their emotions onto the canvas. Meidner creates a chaotic, crumbling group of buildings and roads that foretells of his view on the incoming madness of the First World War about to shake Germany. The classic circus scene, like Kirchner’s Circus Rider, elevates an exciting public gathering by fragmenting the space through line and color. It conveys a message on the isolation of humans from one another even as cities became epicenters of glamour and progress. Abstraction of soft naturalistic representation in favor of jarring, bold visuals characterize the Expressionists’ style of painting. On the other hand, Robert Delaunay’s painting of the monument of Paris, Eiffel Tower, uses color to illustrate the vibrancy and energy pulsating through Paris after the war. In contrast to Expressionists who highlighted the undertones of ruin found in Berlin, Delaunay rendered a familiar structure of Paris to demonstrate the legacy of modernity and show the energetic atmosphere a city like Paris created.

Living In A Material World

Washington University American Culture Studies L98 2085, Living In A Material World

Modern Literature Collection: The First Fifty Years

“Modern Literature Collection: The First 50 Years” is a digital exhibit to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Modern Literature Collection (MLC), part of the Special Collections in the Washington University Libraries. The digital exhibit is a companion to the onsite exhibit in Olin Library, on display November 2014 – March 2015, and contains everything available onsite, and much more. We hope that through these digitized materials you will enjoy exploring the history of the MLC, as well as the rich contents of some of the writers’ archives.

To search all the finding aids and cataloged items in the Modern Literature Collection and across Special Collections, please visit this page on the Washington University Libraries' website. There you will also find our forms and policies regarding access.

Rights Statement

The digital exhibit's purpose in part is to hold forth the compositional processes of some of the writers the MLC is best known for, and to provide meaningful perspective on their lives and work. Just as the variety and format of materials in the Collection varies widely, so does available information on the origin and copyright ownership of the selected content on display as part of the MLC50 digital exhibit.

Washington University in many cases does not control copyright for individual items—which are being made available for individual viewing and reference for educational purposes only, such as private study, preparation for teaching, scholarship, and research. The Department of Special Collections cannot and does not grant or deny permission to use or publish content in the MLC50 exhibit for which it does not hold copyright. Reproduction, distribution or public display of materials beyond what is authorized by fair use and other statutory exemptions may require consent of the copyright owner.

Whenever possible, University Libraries provides information about rights holders and related facts in its catalog records and other texts that accompany materials, but researchers are ultimately responsible for making independent legal assessment of an item and securing any necessary permission. Information on many writers’ copyright holders and on past literary firms, publishers, etc. can be found in the online WATCH and FOB databases, run by the University of Reading and the Harry Ransom Center.

If you are an individual or institution with information about an item in this digital exhibit, or if you are the copyright owner and believe we have not properly attributed your work or have used it without permission, please contact spec@wulib.wustl.edu.

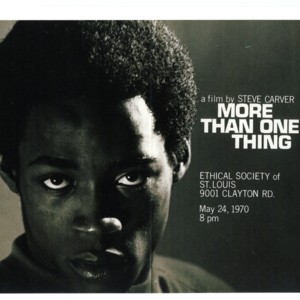

More Than One Thing

Washington University Libraries’ Film & Media Archive is pleased to present this online exhibit to celebrate the preservation of More Than One Thing, a documentary directed by filmmaker Steve Carver. Created in 1968 and 1969 while Carver was a graduate student at Washington University, More Than One Thing explores the daily life of Billy Towns, a young man who lived in the Pruitt-Igoe housing development in St. Louis. Via video clips, audio oral history interviews with Billy and his brother Tommie Towns, never-before-seen still photographs, and, of course, More Than One Thing itself, we hope to help keep this film, and its thoughtful, sensitive take on Pruitt-Igoe alive for future generations.

Preservation of More Than One Thing was made possible with the support of a Basic Preservation Grant from the National Film Preservation Foundation (NFPF).

Music and Racial Segregation in Twentieth-Century St. Louis: Uncovering the Sources

Music is one of the primary means by which racial and ethnic categories are maintained and understood. As Ronald Radano and Philip Bohlman put it in their foundational 2000 book Music and the Racial Imagination, music both “contributes substantially to the vocabularies used to construct race” and “fills in the spaces between racial distinctiveness”—in other words, music sometimes helps build racial barriers and sometimes challenges and undermines them. The fundamental connection between music and race is especially notable in urban areas, where musical institutions, both formal and informal, reflect and shape racial inclusion and exclusion.

St. Louis, notorious for its history of racial segregation but also widely celebrated for its vibrant musical heritage, provides a significant test case for questions about the connections between music and segregation in urban life. The archives of both Washington University (WUSTL) and the Missouri History Museum (MHM) hold many materials related to this rich history. This website 1. provides researchers with a database of relevant sources at these two institutions and 2. draws upon those sources to create an online exhibit exploring key moments in the history of music and segregation in mid-twentieth century St. Louis. We intend this project to be useful to scholars of music, race, and/or urban studies; instructors at high schools and universities; and St. Louisans interested in the cultural and political history of their city.

The Divided City: An Urban Humanities Initiative, a project of the Center for the Humanities and the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, funded by the Andrew W Mellon Foundation.

The Database

During the 2016-17 academic year, Patrick Burke (Associate Professor of Music, WUSTL), with the assistance of undergraduate interns Logan Busch and Courtney Kolberg and the expert archivists and librarians credited below, conducted extensive research in the collections of WUSTL and MHM, searching for any source related to music and racial segregation in twentieth-century St. Louis. That research resulted in a database of over 500 items with full citations and synopses of their content. The database is available here as an open-access Excel spreadsheet that may be downloaded and used by anyone interested.

The Exhibit

The online exhibit tells the stories of five moments, spanning the years from 1923 to 1949, when St. Louis musical institutions either perpetuated practices of segregation or sought to resist them. These stories serve as sobering reminders of the daily indignities that African Americans endured in St. Louis during this era of official segregation. They also reveal the courage and persistence of St. Louisans who fought against racial discrimination and inequality. And they demonstrate that music, often seen as a diversion from politics, was actually central to political struggles over race and the city.

Each page of the exhibit includes images that have been scanned from the archives and information on the kinds of sources featured and what researchers can learn from them.

(A note on language: archival sources from the 1920s-40s often use racial identifiers, such as “Negro” and “colored,” that were considered polite at the time but may now seem dated or offensive. When quoting such sources, this exhibit retains their original wording; otherwise, it follows modern usage.)

Credits

Project Director: Patrick Burke (Associate Professor of Music, WUSTL)

Text: Patrick Burke (page on W.C. Handy written by Courtney Kolberg and Patrick Burke)

Site Design and metadata creation: Shannon Davis (Digital Library Services Manager, WUSTL)

Research Interns: Logan Busch (WUSTL ’17), Courtney Kolberg (WUSTL ’17)

Image Scanning: Patrick Burke, Jaime Bourassa (Associate Archivist, MHM), Teresa Yarber (Digital Imaging Specialist, WUSTL)

Valuable research assistance was provided at MHM by Emily Jaycox (Librarian) and Molly Kodner (Archivist), and at WUSTL by Douglas Knox (Assistant Director, Humanities Digital Workshop), Vernon Mitchell (Curator of Popular American Arts), Miranda Rectenwald (Curator of Local History), Sonya Rooney (University Archivist), and Brad Short (Associate University Librarian for Collections).

Nature-Urbanism-Disaster: The Expressionist Zeitgeist

Nature—Urbanism—Disaster: The Expressionist Zeitgeist is a digital exhibition catalogue that analyzes the ways Expressionists in France and Germany responded to the great cultural, historical and political upheavals of the early twentieth century. Curated by the students in Dr. Sarah McGavran’s writing-intensive course Fauvism and Expressionism in Europe, c. 1905-1945 at Washington University in St. Louis during spring semester 2015, it consists of this introductory section and eleven digital exhibitions. Each of the digital exhibitions includes a thematic introductory essay and three catalogue entries on individual works of art. In this way, the students illuminate how specific artworks in the internationally renowned collections of modern art at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum and the Saint Louis Art Museum bespeak broader Expressionist themes of nature, urbanism and disaster.

For links to the students' digital exhibitions, including the catalogue entries on individual artworks, click here.

Background images:

LEFT: Henri Matisse, Bathers with a Turtle, 1908. Oil on canvas, 71 1/2 x 87 in. Saint Louis Art Museum.

RIGHT: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Portrait of a Woman, 1911. Oil on canvas, 31 3/4 x 27 3/4 in. Saint Louis Art Museum.