Fig. 1: Max Beckmann, The Dream, c. 1921

Oil on canvas

71 3/4 x 35 7/8 inches

Saint Louis Art Museum

Max Beckmann became an established artist at a very young age. In 1906, at the age of 22, he had works on show at the relatively progressive Berlin Secession, and earned a scholarship to study in Florence. His works, at the time done in an Impressionist style, were popular with critics and viewers alike.[1] However, after the passing of the Great War of 1914-1918, viewers who were originally acquainted with Beckmann’s works were surprised to find him painting in a new style that departed greatly from the painterly strokes and atmospheric, mood-inducing color palette that defined his earlier works. The Dream is one such work, that hints at Beckmann’s change in direction towards a more somber style of expression in his art after his traumatic experiences in World War I.

The Dream depicts five figures as well as multiple objects in an interior space without a fixed perspective. This collapses the space into a claustrophobic area in which each figure is too close for comfort with regards to everyone else. Each figure, except for the girl in the center, is shown as either obviously physically handicapped or mentally detached from reality. At the top right corner, the man with the mustache has lost both hands; below him another man has lost both legs and has to support himself using crutches. The old man on the top left, though having all of his limbs intact, appears to be blind, as the card he is holding reads, “Danket Gott für Euer Augenlicht und vergeßt des armen Blinden nicht,” which means “Thank God for the light in your eyes, and don't forget the poor blind man.”[2] At the bottom, a woman plays a stringed instrument with her eyes closed and a delirious smile, suggesting denial of reality. Lastly, there is the girl in the center, sitting on a crate, who seems to be the only person who is both physically and mentally sound in the entire piece. The rest of the composition is filled with various knick-knacks, suggesting horror vacui, or a fear of empty space. This compressed space with its delusional figures incites discomfort in its viewers, whether at first glance or after careful observation, hinting to Beckmann’s frame of mind when he painted it.

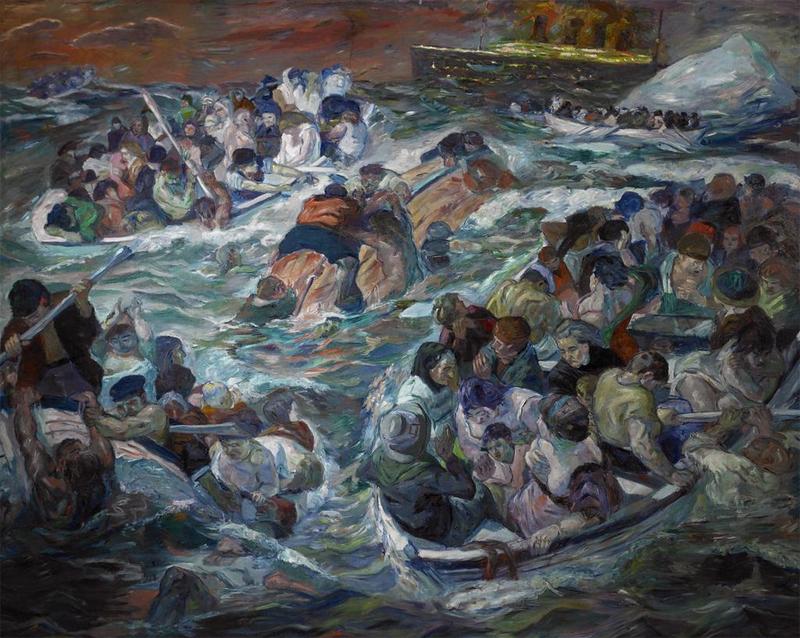

For viewers who were familiar with Beckmann’s works from before the war such as The Sinking of the Titanic (Fig. 2), the choice of such esoteric subject matter would not have been the first thing that they notice; rather it would have been the shift in painting style. Beckmann has abandoned the copious use of dramatic, saturated colors throughout the whole composition in lieu of sparingly placing them in a picture plane occupied mainly by savannah-like colors. Even when using these saturated colors Beckmann controls their intensity, making sure that they do not distract the viewer from the rest of the piece. Next, these viewers would also find that Beckmann no longer uses the painterly style like that of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Instead, he relies heavily on drawing to describe the figures and objects, giving them each a definite outline. This shift to drawing also allowed Beckmann to simplify the forms in his composition, adding to his steady shift in focus to a certain amount of abstraction in his paintings.

Fig. 2: Max Beckmann, The Sinking of the Titanic, 1912-13.

Oil on canvas

104 1/4 x 130 inches

Saint Louis Art Museum

Just what was it that caused Beckmann to have such a great shift in both subject matter and style? Without a doubt, it would be his experiences as a medical orderly during World War I that shattered his ideals and philosophy, causing him to discard his naiveté and take on an even more somber view of the world around him. Before his enlistment into the war, he thrived on stories of contemporary destruction and conflict, depicting them in works such as the aftermath of the earthquake in the Scene from the Destruction of Messina (1909), as well as The Sinking of the Titanic, both which are currently on view in the Saint Louis Art Museum. In his diary entries, he reveals that his fascination with such subjects was due to an obsession with space, such as this entry about the Messina earthquake:

I want space, space. Depth, naturalness. As far as possible no violence. And austere colors… The pallor of an atmospheric storm and yet all of our pulsating sensual life. A new, still richer variation of violet red and pallid yellow gold. Something rustling and rank a like a lot of silk that one peels apart, and wild gruesome glorious life.[3]

Beckmann believed that the presence of conflict and destruction integrated humans into nature and brought them away from the trappings of the modern consumerist society. He also felt that by painting he was the “creator of a personal world…populated with figures imbued with the expressive power of myth.” [4] As such, the figures he depicted are usually in struggle, ushering a new and vital humanity in the process. This explained his choice of subject matter before the war—although works like Destruction and Sinking dealt with themes that are as equally dark as the paintings that he did after the war, the underlying intent was different; Beckmann wanted to elevate these contemporary events to the status of myths. This also justified his painterly style in the pre-war years, which is well suited to capture the grandeur of humanity’s various struggles.

Fig. 3: Max Beckmann, Self-Portrait as Clown, c. 1921

Oil on canvas

39 2/5 x 23 1/5 inches

Von der Heydt Museum

Beckmann initially welcomed the coming of war, for the same reasons that were just described above. His earlier letters from the front showed an excitement at seeing the destruction around him, for it gave him inspiration for potential works. However, the trauma of the war eventually overcame him, causing him to abandon his original philosophy. He began to see life as futile and meaningless; the vast space that used to fascinate him had become an oppressive vacuum.[5]

This sense of futility is substantially represented in The Dream, showing the struggles of mankind not as something to be glorified, but rather as a cruel joke. The blind man is reminiscent of a street performer attempting to earn enough to get by. However, this struggle to survive is seen as silly as he is attempting to play two instruments at once, yet he is unable to get the attention of any of the other figures present in this space. By having her eyes shut and her legs around the instrument, the woman playing the stringed instrument she is unable to play the properly, no matter how hard she might try. As such, this exemplifies her foolishness. Though he is struggling through the use of crutches, the man who lost both his legs is clothed in a polka dotted shirt and pants like that of a clown, causing the viewer to be unsure as to whether they should pity him or mock his circumstances. Lastly, the man with missing hands is in an orange striped jumpsuit and is carrying a fish, which is already absurd on its own. More importantly, he is attempting to climb a ladder to escape the chaos, which the viewers can plainly see is a dead end, as the ladder ends right after a few steps. However, the man’s eyes are shut and he is unaware of this fact that lies before him. All in all, these figures show not only the obvious physical repercussions of World War I on Germany, but also an entire generation’s denial of what had happened and the futility in their struggles to react in their denial and escapism.

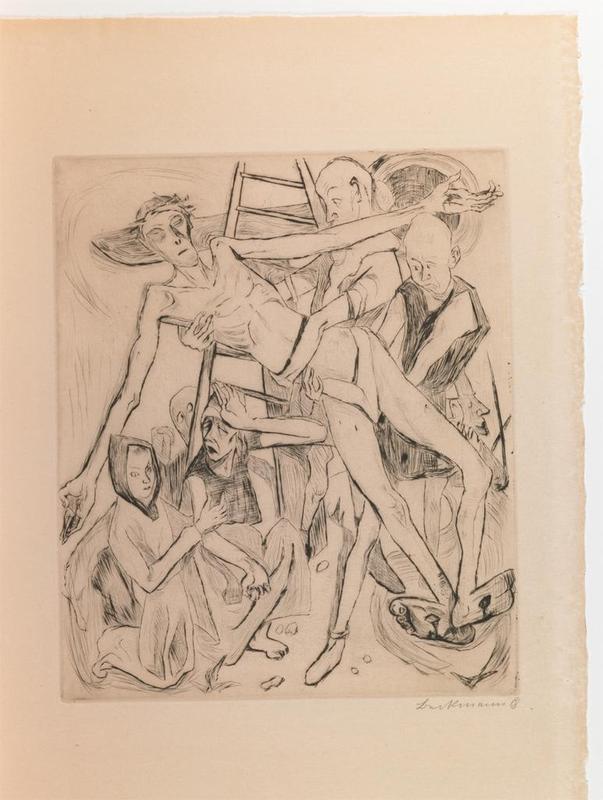

Fig. 4: Max Beckmann, Descent from the Cross, c. 1918

Etching

10 1/16 x 12 1/16 inches

Saint Louis Art Museum

Special attention must be given to the girl at the center, who is carrying a Punch doll in one hand and stretching out the other. She is the only figure with her eyes open in the entire piece, and her look is one of disapproval and judgment. Being depicted as one of the younger generation, the girl’s distance from the other figures in denial is emphasized further. The Punch doll that she carries is a character from a traditional street show that is often excessively violent and senseless, reflecting the meaninglessness and violence of World War I. Her outstretched hand is a recurring motif that shows up in a number of other Beckmann works, such as his Self-Portrait as Clown (Fig. 3). The gesture of the outstretched hand invokes the Passion of the Christ, which originally developed from illustrations of religious imagery such as the Descent from the Cross (Fig. 4). Beckmann usually reserved this motif when depicting himself in his paintings, which stemmed from his attempt to draw parallels of martyrdom between himself and Christ. As such, it is also possible that the girl in the center of The Dream might be a self-representation of Beckmann himself, as someone of the younger generation who has seen beyond the frivolities of existence and mankind’s struggles against it. By linking the girl with Beckmann himself and Christ through the gesture, he also shows that the girl has gone through a degree of suffering due to the war as well, albeit without any visible crippling physical or mental aftermaths. Beckmann has had a similar experience with World War I, having being discharged from service due to mental breakdown, but had recovered somewhat since.

From the way that his painting style has changed between the prewar and postwar period, as well as the imagery that is present, it can be seen that The Dream is a culmination of Beckmann’s takeaways from his experience of war, and that his style and choice of subject matter both revealed this change in his philosophy. No longer a romantic who believes conflict to be beautiful and something mankind should aspire for, he shows bluntly his revised cynical worldview through the ironic subject matter.

[1] Art Directory. “Biography, Max Beckmann.” Accessed February 27, 2015. http://www.beckmann-max.com.

[2] Maur, Karin Von, Max Beckmann: Meisterwerke, 1907-1950, Stuttgart: G. Hatje, 1994, 88, quoted in Mukhlis, Amin Carl, “Aus tiefem Traum verschwand ich in den tiefsten des Nichtmehrseins: Fragen der Ikonographie im Werk Max Beckmanns.” PhD diss., University of Stuttgart, 2008.

[3] From Beckmann’s diary entry for January 28 1901. Quoted in Wendy Beckett, Max Beckmann and the Self (New York: Munich, 1997), 21.

[4] Matthias Eberle, World War I and the Weimar Artists (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 76-77.

[5] Ibid, 88.