Fig.1: Max Pechstein, Bay of Monterosso, c.1917.

Oil on panel

Oil on panel, 28 3/8 x 94 ¾ inches, in 3 panels

Saint Louis Art Museum

On October 8 1914, three months after the outbreak of World War I, the Japanese occupied Palau, a German colony in the South Seas. At that time, Max Pechstein had been living there for six months.[1] Within a month, however, he was deported off to Nagasaki, and thereafter by way of a complicated journey eventually made his way back to Germany in 1915, where he quickly enlisted for military service. [2] He never set foot on Palau again.

Bay of Monterosso was painted two years after Pechstein left the South Seas, in 1917. The painting is a triptych made up of three panels and depicts a beach scene. In the left panel, several figures unload a fishing boat, while another group tends to a boat in the background. In the center panel, several figures fish off a boat with a net at the top of the panel, while at the bottom a figure tries to push a boat out into water. Lastly, on the right panel, a group of figures attempt to pull a boat up onto shore. The entire scene is rendered in smooth yet loose brushwork in a yellow-orange palette, save for the sky and the water, which are purple and copper green. Upon close observation one finds that there is also incoherence in depicting the perspective, for the top fishing boat in the center panel is larger than the fishing boat in the background of the left panel, which flattens the space only in the center panel. The relatively subdued palette and simple, nondramatic subject matter convey Pechstein’s yearning for a simpler time during World War I, which was tinted by his experience in Palau before the Japanese evicted him off the island. However, at the same time, Pechstein also addresses the need for human cooperation during the war period through the imagery in the painting.

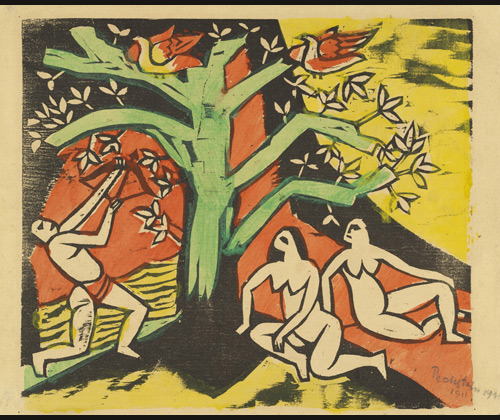

Fig. 2: Max Pechstein, Killing of the Banquet Roast, c. 1912.

Woodcut with watercolor

9 7/16 x 11 7/16 inches

Museum of Modern Art

A member of the German Expressionist artist group Die Brücke (“The Bridge”) since 1906, Pechstein shared the group’s desire to return to a so-called primitive state, to escape from the city and to reconcile art with nature. As a result, Pechstein’s works at the time, like those of his peers, consisted mostly of primitivist nudes, as in his woodcut Killing of the Banquet Roast (Fig. 2). [3] However, by April 1912, Pechstein had started to fall out with the rest of the Brücke members due to internal politics arising from his career successes.[4] Gaining an increased conviction to leave Berlin to “escape the city,” Pechstein made many trips in 1913, of which included Florence and Monterosso, Italy.[5]

In April 1914, Pechstein set off for Palau with Lotte, his wife. The decision of Palau as a destination is no doubt due to the influence of Paul Gauguin—Pechstein had access to Gauguin’s writings and paintings made during his time in the South Seas from 1891 until his death in the Marquesas in 1903. Through his works, Gauguin made it appear that the South Seas was an Arcadia largely untouched by European civilization, with its peoples living closer to nature. The possibility of experiencing living amongst such people was incredibly attractive for Pechstein. Wanting to experience the same close connection to nature that Gauguin ostensibly did, and partly to fill the gap in his life for the theory and practice of his ideals caused by his departure from Die Brücke, Pechstein decided to leave for Palau as early as 1913. [6]

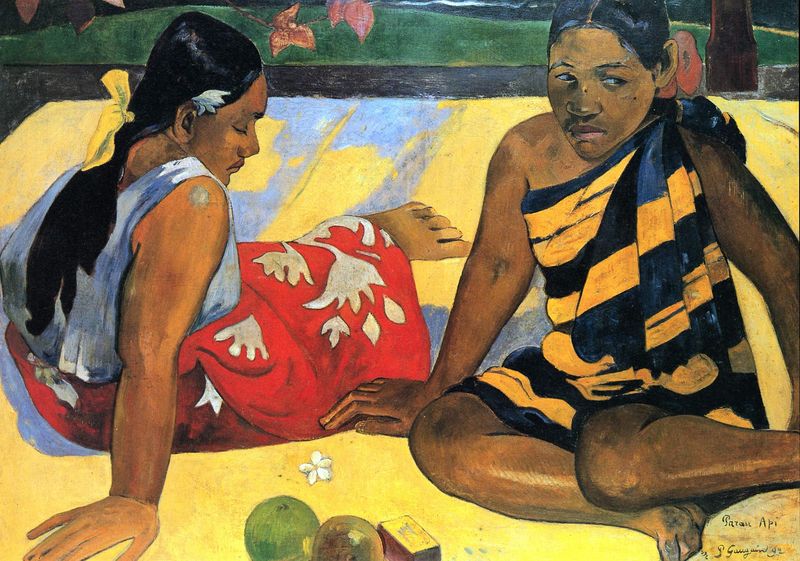

The influence of Gauguin’s writings and works and Pechstein’s own travels to Palau are evident in the triptych. Although the work is titled Bay of Monterosso, an Italian town that Pechstein had visited back in 1913, the color palette used is more reminiscent of a scene from the South Seas. The dark orange used to describe the skin color of the figures brings to mind native South Seas islanders, like those in Gauguin’s Two Women of Tahiti (Fig. 3). Similarly, the orange-yellow of the sand in Pechstein’s triptych suggests bright sunlight, which is also present in many of Gauguin’s Tahiti images. As for the subject matter, everyone is working together to fish —a rather simple activity, close and intimate with nature. This sort of cooperation brings to mind what Pechstein observed during his time in Palau, “life and labor do not exist side by side like foreign or opposing elements. They are one entity and flow into each other.”[7] This sort of idealization of the natives shares similarities with most of Gauguin’s works.

However, Pechstein is shown to routinely ignore colonial realities that did not fit into his idea of Palau. For example, his idea of a Palauan community spirit was actually caused by the commercial exploitation of the natives by the colonialists, resulting in them having to band together to survive.[8] From this, we can see that Pechstein has a deep-rooted idealization of Palau society, which explains the same idealization present in Bay of Monterosso. This can also be the reason for Pechstein’s decision to make this painting as a triptych. Traditionally, triptychs were reserved for religious imagery, and Pechstein appropriating the format shows how much he valued his experiences back in Palau.

Pechstein’s experiences right after he was deported off Palau, up until when he painted Bay of Monterosso in 1917, were not lacking in hardship. Although he arrived at Palau in first class, due to the lack of money he had to travel most of the return trip between the decks, sharing rooms with people of different ethnicities. He had not had such an experience before, and did not enjoy it.[9] On the leg departing from New York, he even had to do manual labor for the first time on a Dutch ship in order to secure passage. According to Pechstein the work conditions were terrible and remuneration little, and he essentially lived a slave’s existence. Furthermore, the other laborers of various nationalities presented a type of non-ideal primitivism too close for Pechstein’s comfort.[10] To cope with the hardships he often daydreamed to escape into an imaginary, idealized world, similar to what he was doing when he painted Bay of Monterosso.[11]

As with Max Beckmann and André Derain, Pechstein’s war experience was unique and shaped his worldview accordingly. Although trained as an infantryman and eventually sent to the frontlines, Pechstein was only in the trenches for two months before his officers noticed his artistic talent and withdrew him from fighting, making him do cartography work instead.[12] As a result, Pechstein did not see comparatively that much fighting and death, similar to the case of Derain, which allowed him to sustain less trauma from the war. Another reason Pechstein maintained his psyche was through his optimism—appreciating the beauty of the surrounding landscape, as well as maintaining camaraderie with his fellow men while in the trenches.[13] This optimism is the same coping mechanism he used when he was working on the Dutch ship, and highlights his disposition towards nostalgia. It thus explains his choice of making paintings of previous travels such as in the Bay of Monterosso, and at the same time the reason why Pechstein refrained from making paintings that dealt with his trip back to Germany or his war experience.[14]

In 1917, Pechstein received a new posting in the Air Force, which allowed him to return to Berlin[15]. It was at this time where he was able to find time to work on artworks amidst his Air Force training, producing around 130 paintings, one of which was Bay of Monterosso.[16] At this point in the war, Pechstein had long since got over his initial enthusiasm, and was now hoping for an end to it.[17] This might explain why in his triptych the figures are clothed in contemporary European dress instead of being in the nude, and why he names the piece Bay of Monterosso instead of something related more closely to Palau. By referencing the Italian town, Pechstein brings his vision of a harmonious mankind straight up to the context of Europe, optimistically wishing for the war to end and for peace to arrive. By having a sizeable amount of figures in the composition, especially in the right panel, Pechstein shows that peace cannot be achieved alone; rather it requires commitment from everyone. Thus Pechstein with this triptych simultaneously looks back to the days of Palau long past, while also looking forward to a future without war.

Pechstein’s experiences since 1912 were incredibly complicated, yet each experience is crucial to shaping him as a person and as an artist. His involvement with Die Brücke informed him of the primitivist aesthetic, igniting his fascination with the exotic and a need to return to nature away from the trappings of modern civilization. This was fueled further by his falling out with the Brücke and Gauguin’s accounts of his Tahiti experience, which led to Pechstein’s own trip to Palau. The sudden uprooting from Palau, while abruptly removing him from his paradise on earth, made it possible for him to look back afterwards with Sehnsucht, or nostalgia, and depicting those feelings in his work. His odyssey back to Germany, as well as his military service exposed him to previously unknown hardships, which made him further treasure those memories of a harmonious community, albeit containing personal bias. It is with those memories and wishes for a return to harmony in a war-torn Europe, which culminates in Pechstein’s Bay of Monterosso.

[1] Jill Lloyd, German Expressionism: Primitivism and Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 200, 211.

[2] Bernhard Fulda and Aya Soika, Max Pechstein: The Rise and Fall of Expressionism (Boston: De Gruyter, 2012), 165-172.

[3] Tanja Pirsig-Marshall, “Dream the Myth Onwards: Visions of Arcadia in German Expressionist Art”, in Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse: Visions of Arcadia, ed. Joseph J. Rishel (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2012), 198.

[4] Fulda and Soika, 121.

[5] Ibid, 130.

[6] Lloyd, 206.

[7] Ibid, 204.

[8] Ibid, 204-205.

[9] Fulda and Soika, 166-168.

[10] Lloyd, 211.

[11] Fulda and Soika, 172-173.

[12] Ibid, 178, 181.

[13] Ibid, 179.

[14] Ibid, 201.

[15] Ibid, 194.

[16] Ibid, 196.

[17] Ibid, 183.