André Derain is well known for being a co-founder of Fauvism, along with Henri Matisse. In 1904 they, along with Vlaminck and several others, explored the idea of expressing emotions through bright, strong color. They rejected the Impressionists’ shallow-seeming emphasis on seeking pleasure. They also disagreed with the Impressionists’ emphasis on depicting the subject matter in one specific moment of its existence, believing that they were unable to capture the essence of what they paint. Instead, according to Matisse, they returned to simplicity, directness, pure colors and decorative qualities, in order to communicate said essence of the subject matter.[1] To achieve this aim, they pared down and simplified their descriptions into blocks of pure, unmixed color. Their palette choice did not usually reflect the local color that the scene actually possesses, which eventually earned them the label of the Fauves (“Wild Beasts”) in 1905.

Although Derain mostly worked with landscapes, he also did portraiture at that time, such as one of his fellow artist Vlaminck (Fig. 2). In that portrait, Vlaminck’s hair and mustache are rendered in a flat patch of orange, and his coat is simplified to the point that the green paint is not even covering the entire surface. Lastly, the background, with its splash of color lacking suggestion of depth, best encapsulates the abstraction and simplification that are indicative of Fauvist visual language, overall emanating vibrancy from the entire piece.

Fast-forward to 1928, a decade after World War I. Derain’s Guitarist shows none of the craze and energy from his Fauve days. The painting depicts a single figure—a woman standing laxly while holding a guitar—standing in an actual tangible space. The full-body format is a clichéd composition, chosen specifically to not shock its viewers in any way. Similarly, the earth-toned color palette chosen is more restrained than Derain’s pure, saturated colors of the Fauve period. The only thing that persists throughout his career is his use of painterly strokes that highlight the materiality of the paint on canvas. This change in direction to a more sober style of painting reflects Derain’s constant search for the method of depiction that suits him the most. Although Derain did participate in World War I, he was an artillery truck driver and did not participate extensively on the frontline in the trenches. On such merit, he would have encountered less traumatic experiences, which would have worn down his mental faculties to a smaller extent than Beckmann, for example. In addition, as a Frenchman, Derain was not on the losing side at the end of the war, and thus would have inculcated less resentment towards his ruling classes at the end of the war as compared to his German counterparts. As such, the war did not dramatically affect Derain’s worldview, allowing him to paint laid-back imagery such as his Guitarist.

Fig. 2: André Derain, Portrait of Vlaminck, c. 1905

Oil on canvas

16 ½ x 13 inches

Musee des Beaux-Arts de Chartes

Looking back at his Fauve days, Derain felt that he had wasted time going down a wrong path with a dead end. With photography becoming more widespread in the nineteenth century, he thought that the Fauves have cultivated a fear of imitating life, which was something in which they can never surpass photography. This resulted in their going in the other extreme direction, which resulted in the characteristic visual language of the Fauves.[2] This was the conclusion that Derain had reached after his continued pursuit for his own form of expression.

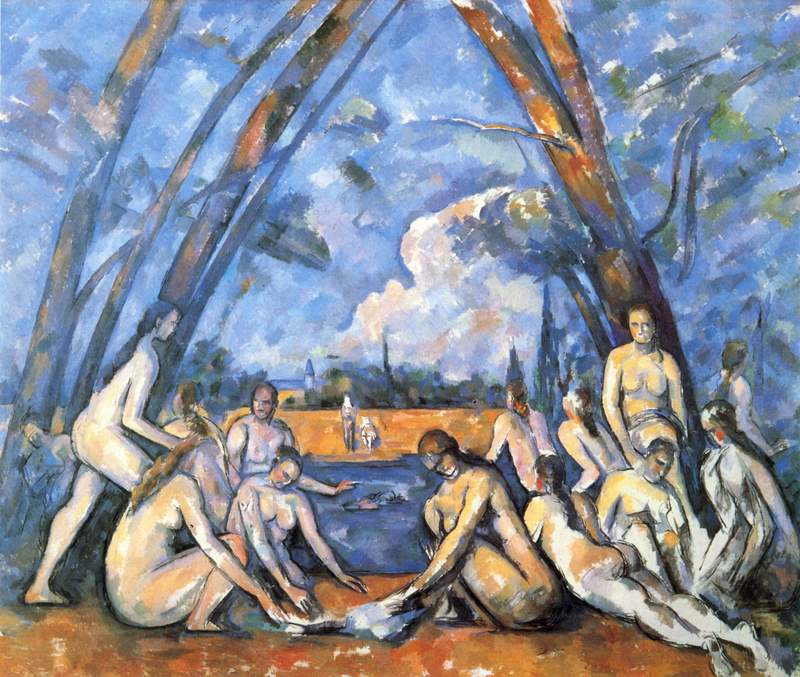

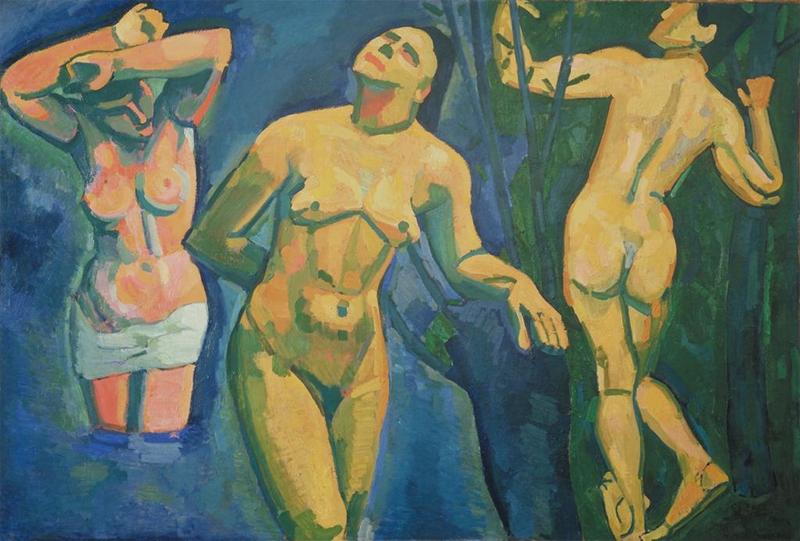

As early as 1907, just two years after the critic Louis Vauxelles had coined the term Fauvism, Derain began to study the works of Cézanne anew. Derain believed that under Cézanne’s simplification of objects into simple geometric form lays a romantic inclination about humanity. By deconstructing figure and form into distinct planes, Cézanne distills the human essence, removes extraneous detail, and ultimately portrays an Arcadia populated with idealized figures. This concern with humanity, not the geometrization of form, was what was most important to Derain about Cézanne.[3] In order to consolidate both aspects of Cézanne’s essence, Derain started moving from the blocks of bold, fully saturated colors that he had been working in for the past two years. His first work after this turning point, the Bathers (Fig. 3), already exhibits a more geometric form as well as a pastel-like palette that is similar to those of Cézanne’s Large Bathers (Fig. 4) the year before.

Derain did not merely restrict himself to studying Cézanne; at other times he had also dabbled in experimenting with other media, such as woodcuts. In 1910, under the influence of Picasso, he had a minor inquiry into Cubism, after which he proceeded to investigate primitivism. It was only in 1912 that Derain once more reconciled himself and returned to trying to express the sentimental and the romantic representation of humanity that he believed Cézanne was striving for.[4]

Fig. 3: André Derain, Bathers, c. 1907

Oil on canvas

52 inches x 6 feet 4 ¾ inches

Museum of Modern Art

Unlike other expressionist painters such as Beckmann who were traumatized by the effects of World War I, Derain appeared to not have experienced the same degree of emotional scarring that leads to a drastic change of painting styles. This might be due to his occupation as an artillery driver—even when on the frontlines the artillery rarely participates in man-to-man combat, instead shelling enemy positions from a distance. As such, there was a lower chance of personally coming in contact with death on a regular basis. This coupled with Derain’s age and maturity in knowing what he wanted to do in his art ensured that his psyche did not break down as a result of the war.[5]

If Derain had any doubts about his artistic direction during the war, the circumstances surrounding Paris afterwards certainly nudged him back into the direction of a political and cultural return to order, which was the overarching trend in France at the time. Even during the war, the French was already starting to rebuild infrastructure that was destroyed in the fighting, opting not to wait until a hypothetical peacetime was reached.[6] After the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, the French government, expecting repatriation money from Germany, accelerated the reconstruction and reestablishment of the economy by giving out loans to businesses to invest. Within a decade, the French regained economic prosperity and self-confidence.[7] The sense of a need to return to normalcy pervaded the entire society, even in the field of art. There began a dislike of the avant-garde in certain circles, believing that they have corrupted the tradition of French culture, partly causing the mood of pre-war society that led them into the conflict.[8] Recent advances in art such as Cubism, Fauvism and even earlier movements like Romanticism were criticized for being self-indulgent and overly individualistic. Their appeal to senses via color was seen as uncouth and barbaric, and there called for a return to a more “civilized beauty.”[9] As the results of war have shown, modernity had let them down, and artists began to look backward into the recent past, celebrating Cézanne as well as the Impressionists.[10]

This atmosphere in the art world about returning to order benefited Derain greatly in that it led him back to Cézanne. Studying the French masters of the recent past, not being too wild with color and compositional choices, in order to be in line with the French tradition—these were the very things that the Paris art scene encouraged at that time, and Derain had touched upon all of those in his search for his own method of expression. The Guitarist,with its earthy palette and mood lighting, not only shows the culmination of his journey of finding himself from the wilderness of Fauvism back into civilization, but also invokes a saudade for the time past, one that was simpler and more ordered as compared to the war and the post-war period. This simplicity can be seen in not just the painting style, but in the subject matter as well—a woman standing and playing a guitar laxly, without any other complicated undertones hinted in the image, fits the want for a simpler time greatly. As such, this painting can be seen as the distillation of everything Derain had stood for at the time, whether it be his pursuit for Cézanne’s brand of humanity in painting, or the sentiment of returning to order that he shared with many of the French people.

[1] Sarah Whitfield, Fauvism (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991), 192.

[2] Ibid, 200-201.

[3] Malcolm Vaughan, Derain (New York: Hyperion Press, 1941), 46.

[4] Ibid, 52-56.

[5] Ibid, 61-62.

[6] Kenneth Silver, Esprit de Corps (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 187.

[7] Carol Mann, Paris Between the Wars (New York: Vendome Press, 1996), 8.

[8] Ibid, 80.

[9] Silver, Esprit de Corps, 228-229.

[10] Ibid, 235-236.