In Charles Hatfield’s Alternative Comic: An Emerging Literature, Hatfield describes alternative and underground comics as “vehicle[s] for the most personal and unguarded of revelations” that are “determine[d] to push past the thematic horizons of the form –and to avoid the colorful yet diversionary byways of familiar market genres” (3-7). Victor E. Hodge’s Black Gay Boy Fantasy does exactly this; the underground comic gives uncensored insight into the typical life of black gay man Neil, while also managing to question and challenge some of the norms within black communities and society as a whole.

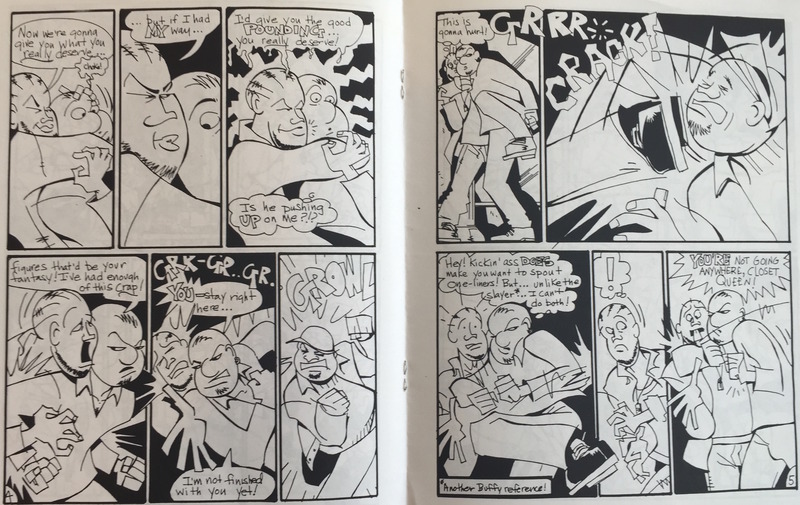

Although homophobia can occur within the confines of many races and spheres, homophobia is often perceived to be more prevalent within black communities. In bell hooks’ Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black, she claims that “there is a tendency for individuals in black communities to verbally express in an outspoken way anti-gay sentiments” (122). While the extent of homophobia in black communities is unknown, these frames from Black Gay Boy Fantasy reflect the direct homophobia hooks references. This issue of the comic opens with the main character, Neil, sharing a kiss with another man. Within seconds of seeing an expression outside the alleged norms of sexuality, a group of black men immediately harass Neil, illustrating and affirming the group’s homophobia.

Author Marlon Riggs provides reasoning as to why this homophobia is so prevalent in black communities. In his essay “Black Macho Revisited,” Riggs argues that black communities’ cultural homophobia is based on “the desperate need for a convenient other within the community, yet not truly of the community –an Other on which blame for the chronic identity crises afflicting the Black male psyche can be readily displaced” (390). Because of this need for a scapegoat, Riggs explains that this Other provides black men and boys who are “maturing, struggling with self-doubt, anxiety, feelings of political, economic, social , and sexual inadequacy –even impotence” with someone they “can always measure themselves and by comparison seem strong, adept, empowered, superior” (390-391).

In the image, the “convenient other” and the “black men and boys” are respectively represented by Neil and the group of men. Through the artist’s illustrations, it is implied that the leader of the group of men is struggling with an internal conflict – possibly his sexual identity. During many instances within the scene, both the leader and Neil make reference to the leader’s homosexuality or possibly bisexuality. At one point, the leader states that if he had his way then he would have give Neil “the good POUNDING that he deserves.” Then near the end of the scene, Neil refers to the man as a “closeted queen.” The leader’s anxiety about his sexual identity offers a possible explanation as to why he initially decided to lash out. He may have harassed Neil as an attempt to try to regain strength and control lost in other aspects of daily life. This scene, as well as Hodge’s comics as a whole, examine what may drive individuals within and outside the black community to commit such actions of homophobia.

Hatfield, Charles. Alternative comics: an emerging literature. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2005. Web.

Hodge, Victor E. "Black Gay Boy Fantasy." Vol. 10. N.p.: New Blood Illustrations, 1998. Print.

hooks, bell. Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking black. Vol. 115. Boston: South End Press, 1989. Web.

Riggs, Marlon T. "Black macho revisited: Reflections of a snap! queen." Black American Literature Forum. Indiana State University, 1991. Web.