Helen Bannerman wrote The Story of Little Black Sambo (1898) to entertain her children while they were living in India. The story has been controversial primarily because of its racist illustrations, which represent a stereotypical picaninny caricature. The term “picaninny” took on pejorative meanings in the nineteenth century when it was developed to represent a racial caricature of black children (Bernstein 34). The book's success led to many imitations and further controversies, as many of these adaptations turned out to be even more degrading and distorted than the original. More recently, there has been a push toward making Sambo appear less racist, which begs the question of why America fell in love with Sambo and why there was and continues to be a continued desire to reproduce it. It’s interesting to think about whether these newer representations further play into Jim Crow ideas or if there is value in trying to reclaim/reimagine harmful representations.

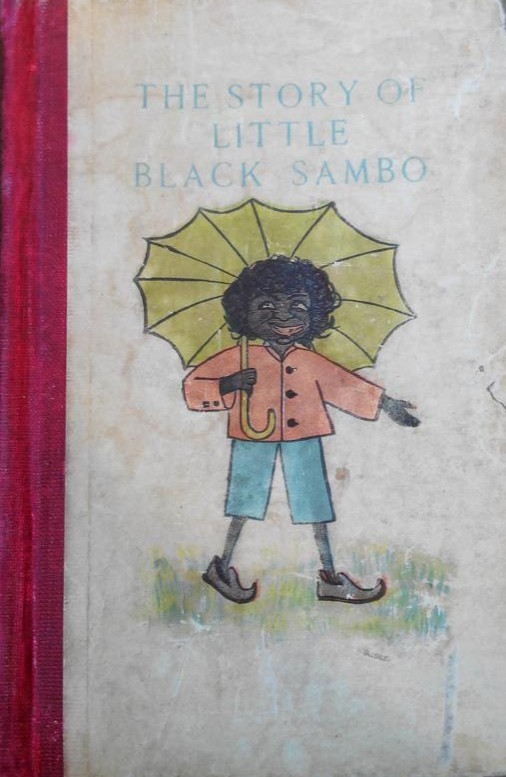

In this image consistent with typical representations of a picaninny, Sambo is depicted as having very dark skin, big white eyes, unkempt hair, a broad nose, exaggerated red lips and a wide mouth (playing into stereotypes about gorging on watermelons). However, unlike a typical picaninny, who is often portrayed in ragged clothes or shown as partially or fully naked (Bernstein 34), this representation of Sambo is more complex in that the story begins with him being presented with beautiful clothes by his parents (however he is in a state of partial nudity for the most part of the rest of the story, as he ends up having to bargain for his life by trading his clothes). But as we can see in this image, he dresses in nice clothes, which is unusual for picaninnies as they are supposed to be comfortable with nudity since they are meant to be savage and uncivilized. Furthermore, as can be seen in the image, Sambo is very crudely drawn and is obviously a caricature. Bannerman could have drawn an Indian character if that was her intention, and as can be seen from her other illustrations of white characters in her books she was capable of drawing realistic, non-caricatured drawings, for instance in her books Pat and the Spider (1904) and Little White Squibba (1966).

Looking at the historical context in which Sambo became popular, we can see that the story of Sambo came to the US during the era of Jim Crow laws (extending from the mid-1870s to mid-1960s). It was a period of systematic discrimination against blacks, where they were treated as second-class citizens and were denied basic human rights. Racist everyday representations of blacks became commonplace, and Bannerman’s Sambo became part of that trend, being reproduced on postcards, stamps, saltshakers, pots, etc. This fascination with Sambo makes even more sense when we look at the common usage of the term “Sambo,” a character that was represented as a docile, happy slave who accepted Jim Crow laws and as such was used to justify segregation (in comparison to the much feared and rebellious Savage or Brute stereotype). “The publication of Bannerman's book, and the subsequent profusion of images of Sambo and similar stereotypes made them central to the cultural milieu of the Jim Crow era. These symbols reinforced white dominance and black subordination during the era of segregation” (Nuruddin 291–338). Bannerman’s racist imagery thus only further reinforced ideas of black difference already at work.

Many African Americans now collect racist items and depictions of Sambo as memorabilia and some have produced newer versions of the Little Black Sambo story (Lester 1996). While the former group advocates for preserving these racist images and stories as a reminder of a painful yet never-to-be-forgotten past (Nuruddin 291–338), the latter group seeks to reclaim and reimagine. Yet another group of “Investors/Speculators” are profit-seeking buyers, informed by capitalist ideas and can be seen as feeding of off the pain of a people (Pilgrim 2012). Overall, preserving imagery that worked in tandem with Jim Crow laws could potentially have value, so that one does not put racist ancestors and slave owners in a metaphorical museum and think of them as something extinct. Instead it’s important to think of Jim Crow as an on-going war on black individuals and racist imagery such as Sambo and the picaninny can serve as a powerful reminder.

Bannerman, Helen. “Little Black Sambo.”Frederick A. Stokes Co., (1900).

Bannerman, Helen. “Pat and the spider: The biter bit.” James Nisbet & Co., London (1904).

Bannerman, Helen. “The story of little white Squibba.” Chatto & Windus, London (1966).

Bernstein, Robin. Racial innocence: Performing American childhood from slavery to civil rights. NYU Press, (2011).

Lester, Julius, and Jerry Pinkney. "Sam and the Tigers: A Retelling of 'Little Black Sambo.’" (1996).

Nuruddin, Yusuf. "The Sambo thesis revisited: Slavery's impact upon the African American personality." Socialism and Democracy 17.1 (2003): 291-338.

Pilgrim, David. "Jim Crow museum of racist memorabilia." The Picaninny Caricature. Oct (2000).

Pilgrim, David. "Jim Crow museum of racist memorabilia." Racist New Forms. Jan (2012).