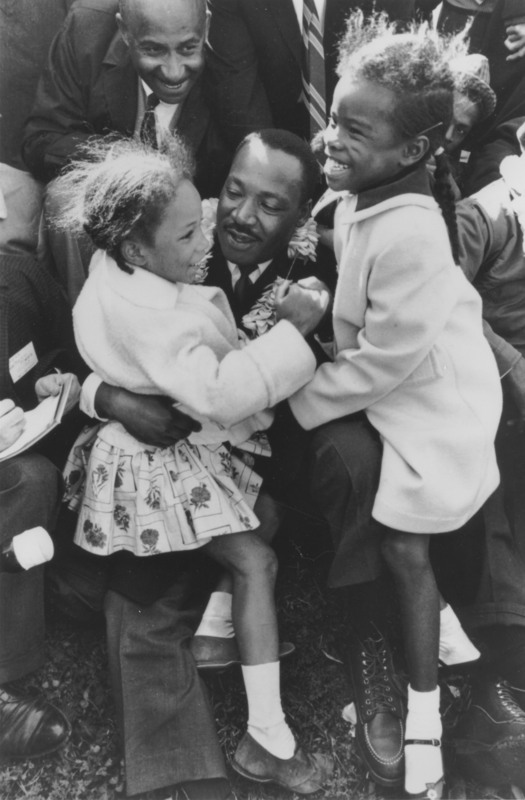

In the image above, Martin Luther King holds two children during the Selma to Montgomery march of 1965, their names are Sheyann Webb and Rachel Nelson West. In contrast to earlier images of college-age demonstrators, these young children have less of an organizing role, however they are as essential in framing the public perception of the movement. King’s attention is directed toward the children, who appear cheerful and unaware that a photo is being taken. Both Webb and West are dressed in their white Sunday best, evoking traditional ideas of innocence. Given that Black children are often perceived to be older and less innocent than their white counterparts of the same age, this evocation of innocence is particularly significant. The photograph creates a distinction between adult protestors and their children, who have some knowledge of the movement’s intent, yet lack a full grasp of its sociopolitical implications.

It is not the image of the children alone that creates a notable photograph, it is the way in which both children and King interact with each other that defines the community-centered focus of the movement. According to Rufus Burrow, Webb’s parents had been involved in the meetings discussing the logistics of the Montgomery march. The image of both young children suggests that in Birmingham and other campaigns, black children and youth had been a formidable force, and Selma was no different (Burrow 246). The photographer also plays an integral role in documenting the presence of children for press coverage. The innocence of children juxtaposed with the brutality of Bull Connor caused viewers to reevaluate the police response to the march to Selma (Hampton 228).

King happily violates an unjust injunction set forth by the local government, which curtailed freedom of assembly to the extent that “not more than three people could walk down the street together in Selma, and there could be no public meetings of more than three persons without permission from local authorities” (Burrow 229-230). The photo represents King’s assertive response to the injunction, as the crowd gathers around to protect him. The children themselves are instrumental in violating the injunction with smiles on their faces. In the photograph, King inclines his head toward the children as he defers to the children’s emotions and voices in the moment the photograph is taken.

Leigh Raiford notes that “photography proved a more accessible, contemplative, and democratic medium than television” (1131). The images of children brought permanence to their legacy: photographers from SNCC and others unaffiliated with mass media at the time could capture their image and disseminate it at will. Additionally, “if photographs could function as weapons in the fight for public opinion, they could also act as shields, offering protection against excessive violence and mistreatment” (1140). While King’s guiding arms appear comforting and protective of the children, it is indeed the children who are aiding King, helping him put forth an image that is not only stately and authoritative but also fatherly and nurturing.

Webb and West are old enough in this photo to comprehend King’s celebrity and the gravity of the moment. Vann explains that their age makes them endearing and photogenic while also presenting them as mature and competent participants in the march. The excited expressions on the children’s faces embody the “beloved community” that grassroots organizations such as SNCC strived to cultivate. In the photo, the lack of empty space evidenced by the gathering of crowds around King demonstrates a sense of urgency at the time the photo was taken. Such photographs were viewed retrospectively as “a vision of utopia seen from the frontlines,” or a tour de force of art, representation, and coming of age amidst police brutality (Raiford 1154).

Burrow Jr., Rufus. “What We Talk about Has Also to Do with the Children” A Child Shall Lead Them: Martin Luther King Jr., Young People, and the Movement. 217-270.

Hampton, Henry, and Steve Fayer. Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement. New York: Bantam, 1990. 218-229. Print.

"March from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama." PBS Online. PBS, 23 Aug. 2006. Web. 28 Mar. 2015. <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/eyesontheprize/story/10_march.html>.

Raiford, Leigh. ""Come Let Us Build a New World Together": SNCC and Photography of the Civil Rights Movement." American Quarterly 59.4 (2007): 1129-1157. JStor. Web. 30 April 2015. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068483>.