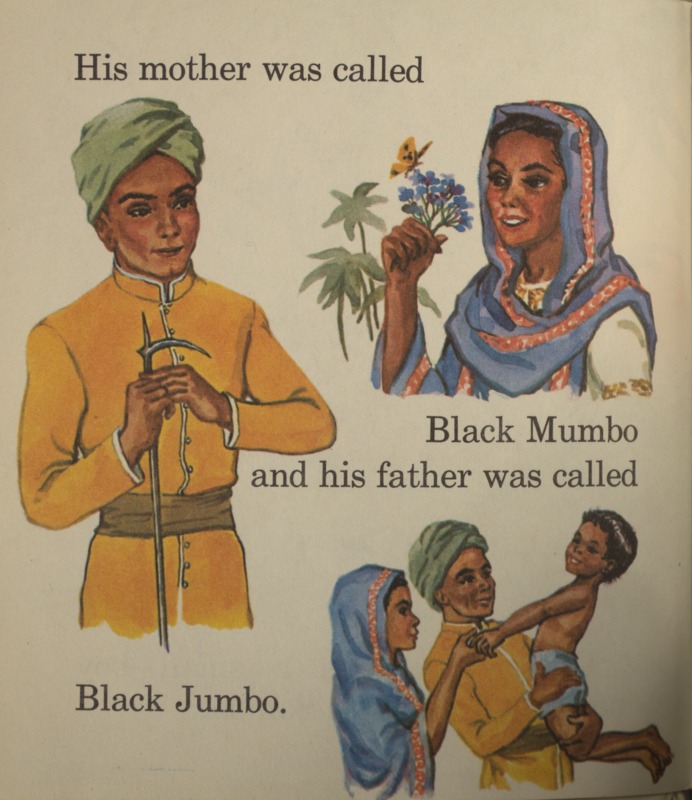

The first scenes of the Sambo story introduce Little Black Sambo’s family to the readers. Violet La Mont’s 1959 edition of Little Black Sambo depicts Sambo and his family as more phenotypically Indian compared to the representations in Helen Bannerman’s original illustrations. Bannerman, the British author of The Story of the Little Black Sambo (1899), also set the story in India; however, she portrayed the characters with crudely drawn Africanized features. This contrast has spurred debate about why Bannerman set a fantastical story starring black characters in an Indian jungle (Susina 243).

In “Reviving or Revising Helen Bannerman’s The Story of the Little Black Sambo: Postcolonial Hero or Signifying Monkey,” Jan Susina questions how the details of Bannerman’s setting further contribute to the colonized portrayal of Blackness as a single, undesirable identity. In both Bannerman’s and La Mont’s versions, they name Little Black Sambo’s parents English names alluding to fearful superstitions and unintelligible nonsense, “Black Mumbo” and “Black Jumbo,” rather than plausibly Indian names. Racist traditions of derision, rather than accurate portrayal of Indian culture, thus dictated the process of assigning names to Sambo’s parents. Furthermore, Susina notes, “Bannerman’s characters do not wear native Indian garb: they appear to be imitating European clothing styles, which are especially noticeable in the illustrations of the parents” (Susina 241). India has a long tradition of caste systems in which the people with the darkest skin color are in the lowest caste; “Bannerman might have assumed ‘one dark-skinned non-Englishman as looking much like another (….). For Bannerman, Indians and Africans were simply other” (Susina 241). Bannerman reveals colonial ideas that the darker a person appears, the more unlike and inhuman they appear compared to white Europeans. By assigning African phenotypes, European culture-copying, and racist English names to Indian identities, Bannerman’s story functions to colonize and devalue both Indian and African identities. The characters and their two unique cultures are commingled primarily in terms of subhuman ubiquitous Blackness. Blackness is used as the idiom with which to reduce the humanity of Indian culture.

La Mont’s more contemporary illustrations work to more accurately depict Sambo’s Indian heritage but also function by contrast to comment on the historic representation of black parenting. She presents “Black Mumbo” in a brightly colored headdress smiling pleasantly at delicate flowers. She portrays “Black Jumbo” in a traditional pagri (a symbol of honor and respect) with a farming tool in hand to show that the family is in the working class caste system. The skin tones of Black Mumbo and Jumbo as well as Little Black Sambo are all a light reddish brown pigment true to an Indian phenotype. The third image on this page comments on the closeness of the family. Black Jumbo holds the young Sambo in his arms as the boy grasps onto his mother’s hands. The mother and father gaze attentively at the happy boy, all three characters physically connected as a family unit. La Mont does not make the same mistake as Bannerman. By recognizing the difference between African and Indian culture, she is able to imagine Indian characters living, working, and parenting much more positively than she would be able to from the lens of black racial hatred. By avoiding the use of Blackness in this way, La Mont’s illustrations show that in the sixty years between the texts, the dominant culture made more refined distinctions and used blackness as an idiom by which to caricature others less predictably.

La Mont, Violet. Little Black Sambo. Racine: Whitman Publishing, 1959. Print.

Susina, Jan. “Reviving or Revising Helen Bannerman’s The Story of the Little Black Sambo:

Postcolonial Hero or Signifying Monkey,” Voices of the Other: Children's Literature and

the Postcolonial Context. New York, NY: Garland Pub, 2000. Print. 237-250.