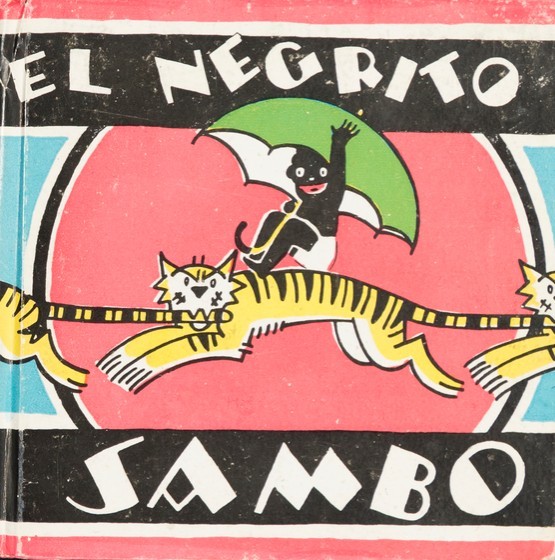

Historically, Moors of North African origin were visually depicted in Spanish paintings as servants and pages. The presence of black children signaled the prestige or social status of wealthy white Europeans, many of whom were interested in the services of African children. Black children portrayed in 18th century Spanish paintings were depicted in the tradition of the black page as decorative element (Pieterse 125). This version of Little Black Sambo, published in Madrid in 1935, follows the tradition of black children represented to entertain and serve at the beck and call of whites. At the same time, American minstrel tradition influences the illustration, thus it is at once a product of American and Spanish racial history.

The name Sambo itself originates from the Spanish word Zambo used to describe a knock-kneed or cross-eyed person (Rout). Thus, Spain’s racial history influences the nature of all Little Black Sambo books, the derogatory name used to describe a little black boy. As such, Sambo’s comical depiction throughout the book and on the cover exhibits aspects of what Pieterse terms the “iconography of servitude” (131). Sambo’s smile and waving hand can be read with the history of Spanish representations of black children: his movements express availability for use by the white European viewer. Additionally, racist discourse during the Spanish Civil War, a conflict that began in 1936, contributes to our understanding of the significance of this version of El Negrito Sambo. In her analysis of Langston Hughes’s time as a correspondent during the Spanish Civil War, Isabel Soto argues that the presence of blacks in Spain, and their role in the African diaspora, was ignored during a conflict that was distinctly racial (134). Thus, the publication of El Negrito Sambo at the advent of the civil war occurred at the intersection of many racial tensions, including those from America.

El Negrito Sambo follows the American tradition of minstrelsy, “a white imitation of black culture,” as Sambo is portrayed with harshly racist imagery (Pieterse 132). Sambo’s jet-black skin and both the exaggerated color and size of his mouth are remnants of popular American minstrelsy of the early 20th century. Minstrelsy was a form of entertainment that Eric Lott describes in his analysis: “The minstrel show was, on one hand, a socially approved context of institutional control; and, on the other, it continually acknowledged and absorbed black culture even while defending white America against it” (38). Despite the fact that Sambo is riding a wild tiger, and the implications of violence this suggests, his bright white eyes and the white dot used to illustrate his nose depict the black boy as comical and carefree in the face of danger.

Pieterse, Jan Nederveen. White on Black: Images of Africa and Blacks in Western Popular Culture. Amsterdam: Koninkllijk Institut voor de Tropen, 1992. Print.

Rout, Leslie B. “The African Experience in Spanish America, 1502 to the Present Day.” Journal of Latin American Studies. 9.2 (1977): 354-355. Web.

Soto, Isabel. “ ‘I Knew that Spain Once Belonged to the Moors’: Langston Hughes, Race and the Spanish Civil War.” Research in African Literatures. 45. 3 (2014): 130- 146. Web.