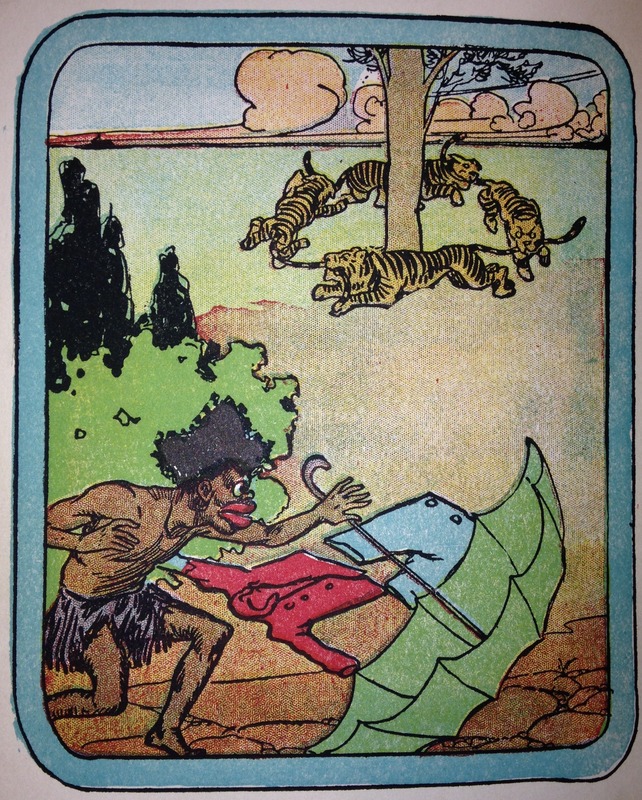

In this illustration from a 1908 version of The Little Black Sambo, Sambo experiences a misadventure with the attire and accessories of European adult life. While wearing a grass skirt, Sambo chases his clothes and umbrella as they fly away in the wind. John R. Neill’s illustration of this scene, in which Sambo cleverly steals back his clothes, reveals a dimension of the nature of the picaninny caricature. While this Sambo has many of the characteristics typically used to create the picaninny stereotype, this particular depiction also contains visual indicators of the menacing and grotesque adult that anti-black racists believed the picaninny would become. This depiction illustrates the relationship between the disordered child and the adult black beast, and this relationship adds a monstrous and grotesque element to Sambo’s picaninny caricature.

Neill’s Sambo has the bright red protruding lips, over-sized mouth, wide shining eyes, and matted hair that typify picaninny misrepresentations of the black child. However, Sambo appears much older than eight or ten, which according to David Pilgrim, is the typical age range of the picaninny caricature (Pilgrim 3). His slack, lean, and seemingly malnourished body is more like the body of a young man in late adolescence. Sambo’s hair appears to be longer, thicker, and more densely matted a child’s hair would be. In addition, the expression on his face does not reflect the befuddlement or dismay of the typical picaninny child in trouble with a goose, piglet, or the other animal with which they were often portrayed. Instead, the turned down corners of his mouth suggest aggression.

These more adult characteristics and the aggressive facial expression suggest that Sambo’s primitive nature has remained unchanged from childhood. He can dress up as a European, but as he approaches adulthood his uncivilized and dangerous identity will become even clearer. This idea is further illustrated by his relationship with the umbrella. In the illustration this symbol of European sophistication and class is escaping him: he cannot grasp the umbrella because ultimately Sambo cannot be civilized by what it represents. The iconic Negro child is now illustrated as a maturing beast, transforming anything attractive or cute about Black childhood into a grotesque ruse for dangerous adult trickery. Ultimately, it is deceptiveness, not intelligence, that allows Sambo to recover his European clothes, therefore making him undeserving of the privileges of western culture that the clothes embody.

Bannerman, Helen. The Story of Little Black Sambo (John R. Neill, illustrator)

Chicago: The Reilly and Britton co., 1908. Print.

Pilgrim, David. "The picaninny caricature." (2000).