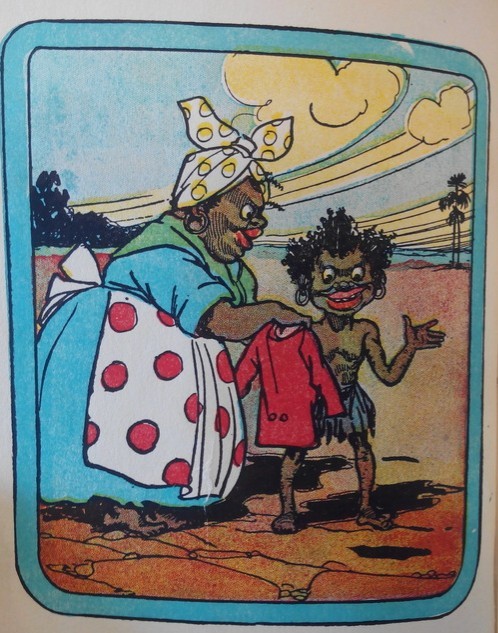

This image is from one of the later re-illustrated versions of Sambo. Printed in 1908, the illustrator used Helen Bannerman’s original story with new images for Sambo, which are decidedly more caricatured and therefore more racist than the original drawings. All of Sambo’s features are more exaggerated here to give him a wild, dehumanized look; his eyes are more bulging, his lips redder and his mouth wider, his nose broader, and his hair more unruly. The artist also makes the face look more cartoonish and comical by making Sambo’s eyebrows appear to meet with his eyes, to make them pop out and give them an almost creepy quality. Furthermore, he is also wearing big hoop earrings (also worn by his mother in this picture, who is illustrated as a quintessential mammy caricature), which have historical roots in slavery. Most striking, however, is how masculinized and older Sambo looks in these illustrations, even though he is supposed to be the same age as in the original story.

Given the far more racist overtones in Neil’s illustrations, combined with the nature of Bannerman’s story, the overall end product comes across as overtly more racist. Here is a child who is in danger of being eaten, but who wouldn’t inspire a lot of sympathy from readers because of the way he is depicted – more animal than human, completely devoid of childlike innocence. This loss of innocence has historically played into ideas that African American boys are juvenile in nature, invulnerable, do not suffer pain, and are not victims. The perception that black children don’t feel pain also played into justifications of slavery, because if slaves were impervious to pain then corporal punishment wasn’t cruel and treating African Americans as insensate second class citizens wasn’t bad (Bernstein 35-35). And as we can see from recent events, these ideas have persevered over time and black children are not really seen as innocent and are often treated and punished as adults. Consider Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old black boy who was playing with a toy BB gun when he was shot, and the officer who did it reported that he had “no clue he was a 12-year-old” (Washington Post 2014). Similarly, Catherine and Curtis Jones, 13 and 12 years old respectively, were the youngest children in US history to be charged as adults for first-degree murder instead of being treated as victims of child sexual abuse (USA Today 2015).

According to a study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Goff 2014) this overestimation of a black child’s age begins at a very young age. The study linked the higher use of force by police on black youth to the common perception that, by age 10, they are less innocent. The study found that police are more likely to use force against black children and that this treatment is based upon dehumanizing stereotypes. The study also cited Department of Education data that said black students are far more likely to be harshly disciplined at school than students of other races who commit the same infractions. Furthermore, statistics show that black males are disproportionately suspended from the nation's school systems (Ferguson 163). This presents a disturbing picture of how educators' beliefs in a "natural difference" of black children and the "criminal inclination" of black males shapes decisions that disproportionately single out black males as being "at risk" for failure and punishment. While white boys are seen as naturally and innocently naughty, black boys are seen as willfully bad. This is possible because teachers attribute adult motivations to black, but not white, children. Essentially this means that many teachers and other school authorities see black boys as “criminals” instead of kids.

The black child, then, is stripped of childhood, and is framed as a menace. The dangers black children face, being routinely profiled and targeted for incarceration, are firmly rooted in history, and racist imagery such as that of John R. Neil’s reflects that history.

Bernstein, Robin. Racial innocence: Performing American childhood from slavery to civil rights. NYU Press, (2011).

Ferguson, Ann Arnett. Bad boys: Public schools in the making of black masculinity. University of Michigan Press, (2000).

Goff, Phillip Atiba, et al. "The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children." (2014).

Neil, John R. Little Black Sambo. Reilly and Britton, Chicago, (1908). Print.

Patton, Stacey. “In America Black Children Don’t Get to Be Children.” Washington Post 26 November 2014 Web. 4 May 2015.

Torres, John A. “Young Killer Nears Prison Release, Seeks Fresh Start.” USA Today 13 Jan 2015 Web. 4 May 2015.