The first version of Little Black Sambo was published by Helen Bannerman in 1899 in London. The illustrations in the book are not culturally congruous; that is, different aspects of the book do not all fit into one culture, but many different cultures. The title of the book, combined with the color of the illustrations and clothing on the characters incorporate African, Indian, and English culture, respectively. This combination creates a book that wholly reflects the postcolonial time period in which Bannerman lived.

The name ‘Sambo’ was commonly used in the late nineteenth century to refer to an imagined black person that was “stereotyped as a slow-witted, comic, black male character” (McGillis 239). However, the Sambo in Bannerman’s book “is not representative of the Sambo figure” (McGillis 239). Bannerman was living in India when she wrote the book for her two young daughters, and the book features Indian characters. Further, the tigers in her illustrations are not native to Africa, but to Asia, and the butter they make, Ghi, is traditionally Indian. This cultural dissonance—the name is that of an imagined black child, while the child presented is Indian—is noticeable in other aspects of the story as well.

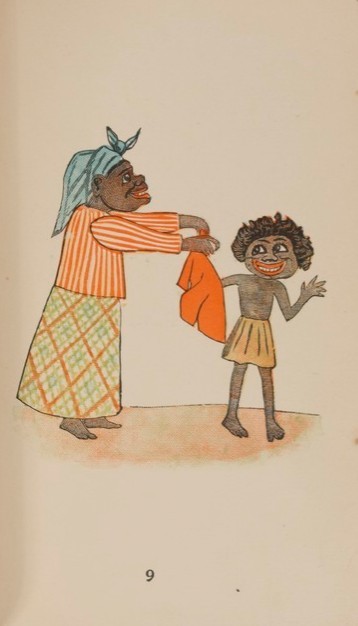

Though the family in the original version is Indian, the clothes that the characters wear are distinctly English: “they appear to be imitating European clothing styles, which are especially noticeable in the illustrations of the parents” (McGillis 241). Sambo, depicted above, wears blue shorts and a red-buttoned jacket with a green umbrella, all items that were English fashion for boys in the nineteenth century. Further, the mother, also displayed above, wears a striped long sleeve shirt and a plaid skirt. The father, not pictured, wears trousers, a button down shirt and a suit jacket. These clothes are all English, and yet the family is decidedly Indian.

These examples of cultural dissonance—the stereotypical black name, the Indian family, and the European clothes—together represent the colonial view that permeated English thought at the time of Bannerman’s publication. In fact, in the late nineteenth century, India was an important colony to England, and thus “Bannerman’s text reflects colonial attitudes toward race” (McGilllis 243). Viewers can interpret the caricatures in the book as unsettling and racialized, yet some critics assert that the problems in the illustrations are “due to their amateur quality” (McGillis 242). Yet, the way in which Bannerman combines the cultures together without acknowledging distinct cultural difference and importance makes it a colonial text. Critics read the impact of the book as Bannerman saying “Indians, as well as Africans, ought to be civilized into European habits and customs and that such natives were culturally inferior to English” (McGillis 241). Though The Story of Little Black Sambo travels through different time periods and countries, the original book, with Bannerman’s text and illustrations, is a decidedly colonial children’s book.

McGillis, Roderick. Voices of the Other: Children's Literature and the Postcolonial Context. New York, NY: Garland Pub., 1999.