Nights and Days of 1964

Cole Porter's "Night and Day" (1932). Link to "Night and Day" Lyrics.

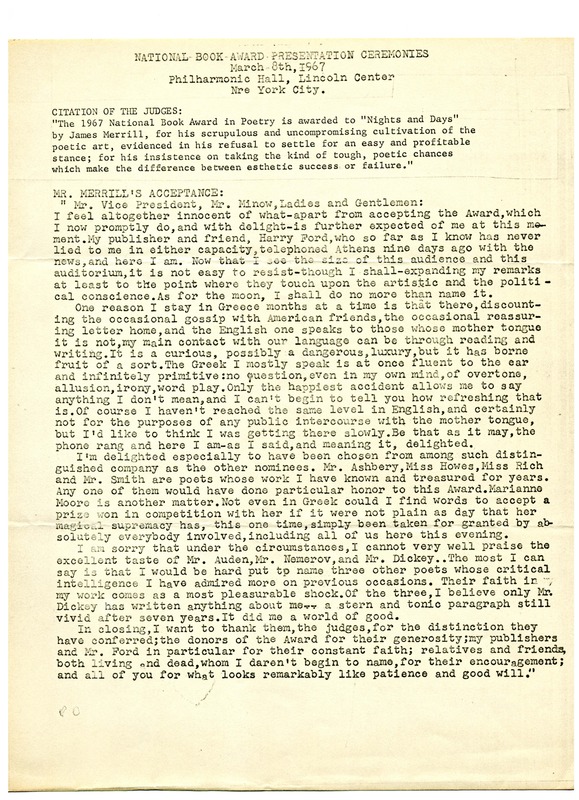

National Book Award Acceptance Speech, 1967. Special Collections, Washington U.

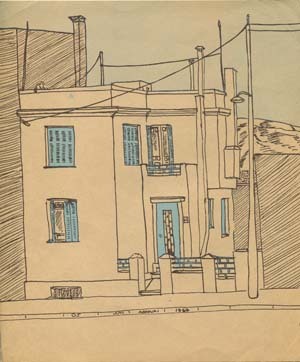

Sketch of Athens house by David Jackson. Special Collections, Washington U.

Mount Lycabettus. Special Collections, Washington U.

Kolonaki Friday Market, Athens, 1961. Photo: Patricia Lawrence.

Palymyra Matron, Mortuary Sculpture, Limestone, 3rd Century. U. of Pennsylvania Museum.

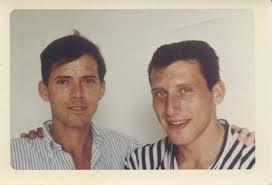

Merrill and Strato Mouflouzélis, Athens 1964. Special Collections, Washington U.

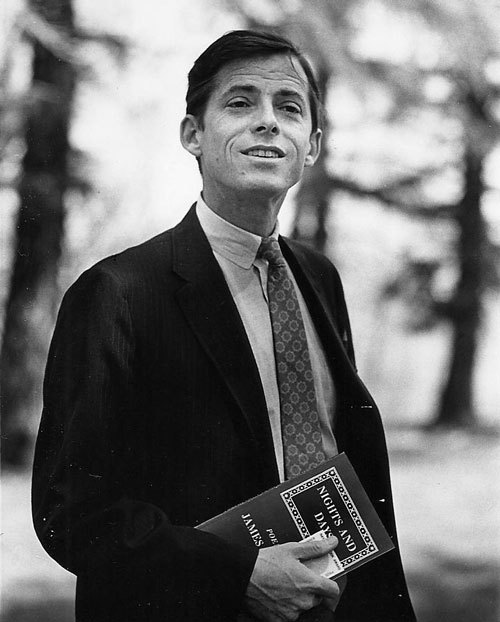

Merrill Holding Nights and Days. Photo: Judy Mofett.

This site provides students and fans of James Merrill with an introduction and background to his poem "Days of 1964." Quoted works are listed below.

The links to this site appear in the left margin. All material is copyrighted. For questions, contact Timothy Materer. Works cited are listed below.

Introduction: Nights and Days of 1964

Context of the Poem

"Days of 1964" is the concluding poem of Merrill's Nights and Days (1966), which won the 1967 National Book Award. It's title echoes Cole Porter's song "Night and Day" (1932). Listening to a friend play Cole Porter songs, Merrill recalled in his memoir A Different Person that the music evoked “a Byronic elite of fox-trotters classy enough to crack jokes while their hearts were breaking” (260). Both Porter and Merrill belonged to a class of wealthy men who guarded their gay identities. Merrill admired Porter, whom he could quote at length (McClatchy 165), and his generation of songwriters: "To their lilt my parents danced and I took my own first steps" (259). The music is populated with the "heartless She, the unempathetic They . . . foremost, of course, the eternal You and I . . . . Would there never be a poem purged of the whole love-addicted crowd?" (260).

Although readers will not find such purgation in Merrill’s poetry, Nights and Days explores the issue of sexual addiction as well as the source of the anxiety he expresses in autobiographical poems such as "The Broken Home" and "The Thousand and Second Night." In "The Broken Home," Merrill considers the effects of his parents' divorce, his fear of his mother's disapproval, and the way he follows in his own way ("inversely") the example of his father's fixation on "sex / And business" (CP 197). Instead of business, his obsession is poetry. But when the "gilt leaves" of a plant he nurtures, like the pages of his poems, grow "Fleshy and green, I let them die" (199). To counter what he feels to be his personal and poetic stagnation, he writes more poems that express the "unstiflement" (200) of his personal story. Nights and Days continues this narrative in the lyric sequence "The Thousand and Second Night," which reflects on his life in Athens. He and David Jackson began visiting Athens in the late 1950s, and in 1964 they bought a house there. In A Different Person, Merrill allowed that there were "many non-libidinous reasons" (190) for the trips to Greece, but a major one was to follow the "faun incarnate in this or that young man without losing ourselves or each other. We were very optimistic to think so” (192).

The affirmative power of "Days of 1964" draws on the context Nights and Days provides. The first of the five sections of "The Thousand and Second Night" opens with the poet waking in Istanbul, alone, depressed and feeling he had "wrecked [his] precious sensibility" (177). It then moves to Athens in part two, where the narrator picks up a truck driver who is "Superb, male, raucous, unclean" (CP 179). Although part three expresses his disgust with his loveless relationships, part four speculates, as in "The Broken Home," that he affirms life through the very poem he is composing. The conclusion implies this affirmation in the dialogue of Scheherazade the storyteller with the Sultan, who of course had intended to kill her until her stories held him spellbound. As in other poems in the volume, such as "Yánnina," the narrator of "The Thousand and Second Night" is escaping to the East, in this case Istanbul, from an unhappy affair that we can assume came from following the "faun incarnate in this or that young man."

The source of his depression is explored as the narrator reflects on his sex life in Athens and Istanbul. In A Different Person, his references to his sexual adventures in Istanbul are brief but explicit: "One winter dusk David and I tried out the louche hamam [bathhouse]. One June, after wishing my mother good night at our hotel, I was roughly treated in a park" (244.) The reference to rough treatment minimizes a dangerous mugging (Hammer 336). In part three, sexual anxiety is suggested by a description of a cache of pornographic postcards, discovered after the death of a relative. The postcards seem related to the erotic photos Jackson and Merrill kept of the men who passed through their home in Athens.

In the characterization of the Sultan, Merrill implies that his father's sensual and dominating nature is found in his son. He speculates that his sometimes insensitive behavior toward his friends shows that he is his "father's own son" (Different Person 225), which he also suggests in "Yánnina." He suspects that the young Greeks he picked up inhabit something like his father’s seraglio of women. After the Sultan and Scheherazade part in "The Thousand and Second Night," "She and her fictions soon were one." But the Sultan "woke in blinding sun, / Too late to question what the tale had meant" (CP 185). As the winding narrative of "The Thousand and Second Night" concludes, the poet like the Sultan is hoping to acquire Scheherazade's spirituality and the will to continue (like the narrator of "The Broken Home") telling her stories. However, as Stephen Yenser observes, if the reader expects the embrace of the Sultan and Scheherazade to imply a resolution to the poem, instead one is "plunged back into the real world of blindness and befuddlement and loneliness. For the Sultan becomes the poet at the beginning, who is also alone, waking, in the Orient, and divided from himself" (Consuming Myth 136).

From "Delusion" to "Illusion"

Although "Days of 1964" offers a sense of resolution to the poet's crisis in Nights and Days, it is highly qualified. To judge by the manuscripts, the poem develops out of the speaker's encounter with his aging housekeeper, Kleo, who is heavily made-up, climbing the "steep hill" (Mount Lycabettus) near his house for a romantic tryst. The first entry of the poem in the 1965 Journal ("Jan 16 65," p. 82) describes the poet's walk to an outdoor market and his affection for Kleo. A later journal entry contains the phrase, "Startled mute, we had stared. Delusion? / I kept on walking" (p. 125); and this phrasing appears in numerous handwritten manuscripts. "Delusion" suggests that Merrill (for such an autobiographical poem, the author's name now seems appropriate) doubts what he has seen. The word is hardly the right one in this case because he has in fact clearly seen Kleo.

Yet "Delusion" is the key word in the drafts. It appears first on p. 86 of the journal: "If this is error delusion, may it last long, long," and once more in the journal on p. 125. In the drafts the word is used 27 times, but in draft 11 the first two letters are whited out and "il" written in to make "de[il]lusion,"which is the only time "illusion" appears in these drafts. Merrill implies his housekeeper is deluded if she believes lipstick and a tight sweater make her sexually attractive, and he too is deluded if he thinks his numerous affairs are genuine love affairs. Klio is described as a Palmyra sculpture not in stone but "lard and horsehair" in a setting that is explicitly "not Olympus," and Merrill admits that he inhabits "a shameless world . . . a region of excrement + wild/flowers" (1965 Journal, p. 83). In the finished poem, Lycabettus is merely littered with "relics / Of good times had by all" but remains a place where, in a confessional passage in the finished poem, "the bud throbs awake / The better to be nipped, self on its knees in mud" (CP 220).

The turn from "delusion" to "illusion" softens the tone and allows for the affirmation of passion he feels for the new lover (Strato Mouflouzélis) he addresses in the poem. If the experience is illusory, then he can only question if he's entered

Into a world of wild

Flowers, feasting, tears−or . . . falling, legs

Buckling, heights, depths,

Into a pool of each night’s rain? (221)

Although his love might be an illusion in the sense that it cannot last, the passion he feels is real and worth affirming: "If that was illusion, I wanted it to last long; / To dwell, for its daily pittance, with us there" (CP 221). He has moved from casual encounters, "knees in mud," to lying awake sharing intimacies with a single lover:

. . . you were everywhere beside me, masked,

As who was not, in laughter, pain, and love. (222)

In fact, the affair with Strato did not last. Stephen Yenser notes that in the poem's concluding lines "the narrative past tense is resonant" (Consuming Myth 117), and Hammer's analysis of the poem shows the significance of the movement in the drafts from the present tense "are" to the past "were" in the line "you were everywhere beside me" (373). As Hammer shows in his biography, the affair was virtually over by the time Nights and Days was published.

In his study of American love poems, Eric Murphy Selinger believes that that Merrill is "our finest postwar love poet" (161). Although they acknowledge that love may be illusion, his lyrics are without the "ironic, even reductive, tone . . . appropriate to a range of poets of the 'modern temper' from Loy to Lowell" (167). Whether Selinger is right about other modernist love poets, Merrill does resemble more the great generation of songwriters that includes Cole Porter and who knew that love affairs may be too hot not to cool down. The lyrics of the Frank Sinatra standard "If You are But a Dream (1942) captures the same hopeful but realistic note as the conclusion of "Days of 1964": "If you are but a dream / I hope I never waken."

Although the Sinatra song lacks the complexity of Merrill's poem, Merrill's drafts show that the poet simplifies his own feelings when he substitutes the word illusion for delusion. Remarkably, the word illusion appears in none of the Washington University drafts with the exception of the revised "de[il]lusion." (Perhaps there are missing typescripts that used illusion.) Hammer observes that Merrill, "Moving, in revision, from 'delusion' to 'illusion' . . . chose a word associated not with madness but conscious, crafted artifice" (375). Hammer might have noted that the word delusion might also be associated with moral failure. The poet consciously chooses to deceive himself and invite an inevitable sense of betrayal. However, using the word "delusion" would have spoiled the passion of, "If that was illusion, I wanted it to last long," as well as his joyful feeling of living in "a world of wild / Flowers, feasting, tears." In Merrill's next volume of poems, The Fire Screen (1969), he addresses in "Matinées" his need for "chills and fever, passions and betrayals, / Chiefly in order to make song of them" (CP 269).

Works Cited

Hammer, Langdon. James Merrill: Life and Art. NY: Knopf, 2015.

McClatchy, J. D. Twenty Questions. NY: Columbia U. Pr., 1999.

Merrill, James. A Different Person. NY: Knopf, 1993.

________. Collected Poems. Eds. J. D. McClatchy and Stephen Yenser. NY: Knopf, 2001.

Selinger, Eric Murphy. What is this Then between Us? Traditions of Love in American Poetry. Ithaca, NY: Cornell U. Pr., 1998.

Yenser, Stephen. The Consuming Myth: The Work of James Merrill. Cambridge: Harvard U. Pr., 1987.