Music in James Merrill: "Matinées" and "The Victor Dog"

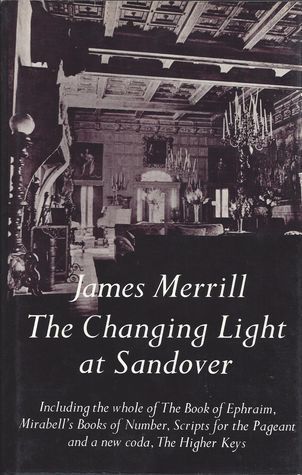

Front cover of The Changing Light at Sandover, showing the ballroom of Merrill's childhood home in the 1930s

Jan Kiepura singing "La donna e mobile" in Rigoletto. YouTube Video.

Lotte Lehmann in Der Rosenkavalier. Lotte Lehmann League. YouTube Recording.

RCA Victor Logo

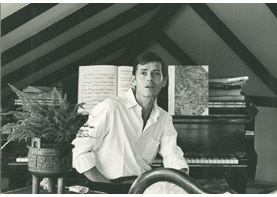

James Merrill in Stonington

Words just aren't that meaningful in themselves. De la musique avant toute chose. . . . . The point about music and song is that theirs is the sound of sheer feeling--as opposed to that of sense, of verbal sense. To combine the two is always worth dreaming about. Collected Prose (55-56).

Merrill and Music

In a draft of "Matinées," Merrill writes that as a child listening to music he felt "tissue of sound becoming tissue, blood . . . / Turned into sound and back to blood again" (Ms. 47 Verso). His long poem The Changing Light of Sandover shows how seriously he meant this claim. The spirits who instruct Merrill (JM) and David Jackson (DJ) through the Ouija board praise "THOSE 2 PRINCIPAL LIGHTS OF GOD BIOLOGY . . . POETRY MUSIC SONG [that] INDWELL & CELEBRATE THE MIND (156). God B[iology] is "life itself speaking" (360) through music that represents the logos of creation: "MIND HAS THIS FORCE . . . IS THE MUSIC DANTE HEARD (161). The spirits explain that a revolutionary music will prepare for a new age that will precede a predicted apocalypse. Its composer will be JM's recently deceased friend Robert Morse (RM), who is being prepared for reincarnation. The composers Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss are RM's major influences as they are for the narrator of "Matinées." Wagner's opera sequence The Ring of the Nibelungs gives romantic and melodramatic dreams of erotic passion to the narrator, and Strauss' Der Rosenkavalier influences his maturing character.

In Sandover Wagner and Strauss appear in person when their works provide background music for angelic visitations. Music from Der Rosenkavalier precedes the angel Michael's visit (355-56), and RM introduces Wagner himself to a group (including JM, DJ and W. H. Auden) listening to Gabriel's lectures: "MASTER, THE CHARMED CIRCLE LISTENING / ABOUT YOU HERE IS YOUR NEW RING" (444). Chords from Wagner's Overture to Parsifal represent the chromatic innovations ("chromatic scales / Beset the dragon" in "The Ring Cycle") that anticipated the avant-garde music of the early twentieth century. RM is instructed in modernist music during "A HARD DAY WITH THE 12 TONE GERMANS" (529), the Viennese composers Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern. Operas by Berg appear in both "Matinées" (Lulu) and "The Victor Dog" (Wozzeck).

RM learns there are limits to avant-garde experimentation. He surprises DJ by explaining that his exercises stay true to the "FREQUENCIES IN WESTERN MUSIC" and the "NEARLY UNBREAKABLE MOLD: /A/B/A OR MAJOR/MINOR/MAJOR" (529). When DJ objects, "But Schoenberg," RM interrupts him: "HE GRASPED THE MOULD- / BREAKING IDEA YET LEFT US WITH THE OLD / INNOVATION ONLY STRENGTHENED IT" (529-30). Although "Matinées" stretches the sonnet form in both meter and rhyme, its traditional mold is also retained. Langdon Hammer emphasizes Merrill's blend of tradition and innovation when he argues that the score of Strauss' Rosenkavalier "set a standard that his poetic music could aspire to. Neoclassical pastiche and Mozartian gaiety, a full, thick, Wagnerian orchestral palette, and an array of atonal effects . . . . " (77).

"Matinées"

Merrill was tutored in the opera form during the Summer of 1937 when his parents were separating. A professional pianist, known for her narration of opera scores, gave piano lessons to Jimmy on one of the grand pianos in the family's music room in their Southampton mansion. In the fall of that year he had tickets for the Metropolitan opera season. (See the link to Merrill's Opera Scrapbooks and Langdon Hammer's biography.) Although the primal scene of "Matinées" is a performance of Wagner's Das Rheingold, the manuscripts also explore the deep influence of what he heard in the family's ballroom. In Ms. 47 a rough stanza compares the boy to his sleeping uncles in the music room:

All that decade those years I was growing up

Nothing fed me more

I sat electric while the uncles dozed

Music that Mozart Bizet Gounod, Strauss composed

Composed my very features in the bars.

47 Verso gives another version of the passage that replaces the term "bars" (as in music) and uses a surprising metaphor about the formative and sacred nature of music:

As at a certain moment in the Mass the climax of the mass

Blood became sacred turns to music & turns back to blood

The red gloom of the veins & Theatre is one

With that inside my skin. O <dear> dead man

How often strains composed by you have since

Compose [sic] my very features in the gloom

Ms. 47 states that the clichés in the "Lives of the Great Composers," such as "his life was music," could be "turned inside-out." But it is a long way from the solemn claim that "Blood turns to music" to the playful cookbook metaphors and the comically vulgar reference to the "elimination [of] sweet Champagne, / Drunk between acts" of the second sonnet. The revisions show Merrill revising raw material though word play and tonal shifts into a brilliantly comic poem.

The composition of " Matinées " follows the time of the intense love affair with Strato Mouflouzélis and the writing of "Days of 1964" in which the speaker chooses passion, "Flowers, feasting, tears," despite knowing that it will lead to heartbreak. The passions described in the manuscript of "Matinées" are more dangerous than in the finished poem. In Ms. 50 operas "invite / Rage & revenge into one's unswept heart brain / To wallow in villainy, ambition, guile." But the worst temptation, described with an echo from T. S Eliot's Murder in the Cathedral, "seems a direct reference to his affair with Strato, who indeed proved to be an "impossible person":

And an irresistible various temptations now took form arose.

To do the wrong thing for the right reason:

To fall in love with the impossible person

To want to die for them

The motive for such behavior is "to sing beautifully about it, " or as in the finished poem:

The point thereafter was to arrange for one’s

Own chills and fever, passion and betrayals,

Chiefly in order to make song of them.

This admission is made in an unusually confessional manner. Robert Lowell admitted in "Reading Myself" that he "struck matches that brought my blood to a boil; / I memorized the tricks to set the river on fire—" In "Matinées" Merrill explores how he learned the tricks to turn his life into art.

His method of coping with such ethical failings is not to repudiate opera as an inspiration but to look for better models. In 50 Verso the Marschallin of Der Rosenkavalier represents the "charm humor pride" missing from characters in Strauss' Salome or Wagnerian operas. In the published sonnet 6 he praises

Lehmann’s Marschallin!—heartbreak so shrewd,

So ostrich-plumed, one ached to disengage

Oneself from a lost love, at center stage . . .

The narrator is still posturing in imagining himself "at center stage" and doing the right thing, forgiving a betrayal, for the wrong reason, to make it the subject of poetry. But these acts of renunciation and forgiveness are on a far higher plane than rage and revenge. Merrill himself followed this ethical model in forgiving Strato's betrayals and attempting to maintain his friendship with his former lover.

"The Victor Dog"

In the final sonnet of " Matinées," we are back with the young opera fan, who sends a thank you letter to the donor of his ticket and tells her he plays his record of the opera's Overture over and over. He is like the "Victor Dog" on the record lable, who "Listens long and hard as he is able," a figure worthy to appear in one of the "Lives of Humble Listeners" mentioned in sonnet two. Ms. 6 has the title, "DOGGEREL <for Mme. Verdurin>." The title hints that, however hard the Victor Dog listens, his comprehension might be no better than Mme. Verdurin's in Marcel Proust's The Captive. At a musical soirée, her

sullen immobility seemed to be protesting against the noddings—in time with the music—of the empty heads of the ladies of the Faubourg. She did not say: “You understand that I know something about this music, and more than a little! If I had to express all that I feel, you would never hear the end of it!” She did not say this. But her upright, motionless body, her expressionless eyes, her straying locks said it for her. (The Captive 2.3)

The reference to the superficial society hostess and the lack of discrimination in the dog's taste (from Bach to Bloch to acid rock) implies Victor is nothing more than a passive listener. Yet his persistence also suggests there is a touch of the artist about him, and Merrill indeed eliminated the deflating title and allusion to Verdurin. The poem is dedicated to his favorite contemporary poet Elizabeth Bishop, and Stephen Yenser believes that Merrill's poem is a response to Bishop's "Cirque d'Hiver." In Bishop's poem a mechanical circus horse (recalling Pegasus) and its rider revolve around a pole as Merrill's dog does around a spindle. Bishop's description of the slow, difficult progress of the toy reflects the painstaking writing of a poem; and the music Victor absorbs represents the challenge of great art.

Victor's role as a musical icon appears in the tightly phrased and puzzling question in the concluding stanza:

Is there in Victor’s heart

No honey for the vanquished? Art is art.

The life it asks of us is a dog’s life.

The wording might suggest that he could withhold comfort to those overwhelmed by a rich musical heritage. However, since he too is vanquished by this beauty, there is no honey in his heart to console him or "us." The drafts of this passage confirm that the Victor Dog is in the same predicament as anyone passionately devoted to art. The revisions take us from the dog as a mere listener to a representative of both a receptive audience and even the creative artist. In Ms. 5 Merrill writes

Stop! In Victor's heart

There's no rest <mercy> for <his> the vanquished, who love art.

The life they give to it is a dog's life

In Ms. 7 the final lines read

Stop! Is there in Victor's heart

No mercy for him the <all those> vanquished by so much art?

The life it asks of him <us> is a dog's life.

"Victor" is vanquished as is both audience and artist because art is long and life short, and the creation of great art is rare and difficult. Merrill is haunted not only by the great poets that precede him but also the musical composers, and most of all by the challenge of joining words to music: "To combine the two is always worth dreaming about."