Poetics of Space: "164 East 72nd Street"

Wikipedia Commons. Originally appeared in Elisa Rolle, Queer Places: Retracing the Steps of LGBTQ People around the World (V. 1.6, 2019).

"Nine levels above gound, like Purgatory." cityrealty.com.

Judy Moffett’s polaroid camera: poet and translator Rika Lesser; Judy, holding the guest book; Merrill; and Jeanette Aycock, Merrill and Hooten's therapist, gathered at the 72nd Street apartment for a viewing of the Voices From Sandover video (June 1991). Photo by Peter Hooten.

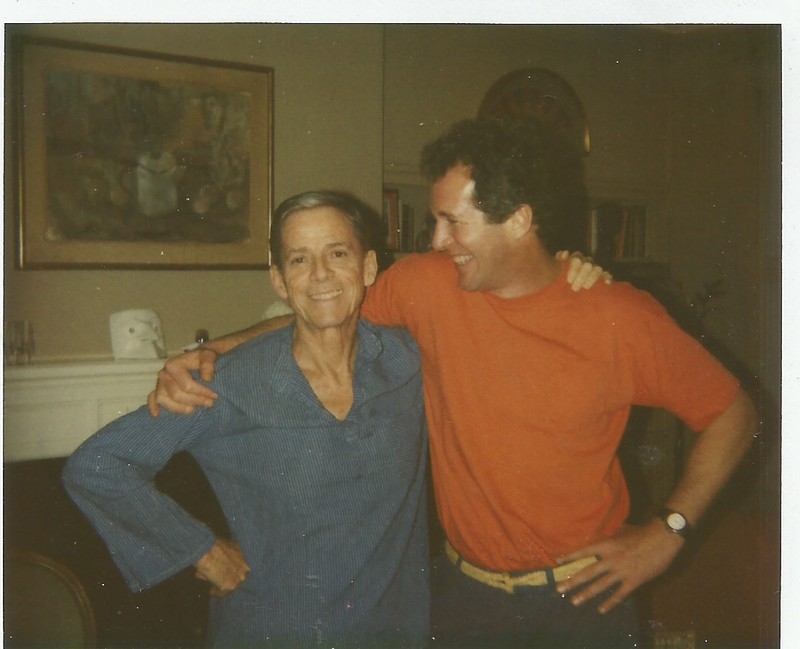

JM and Peter Hooten in the 72nd Street apartment (June 1991). Photo by Judy Moffett.

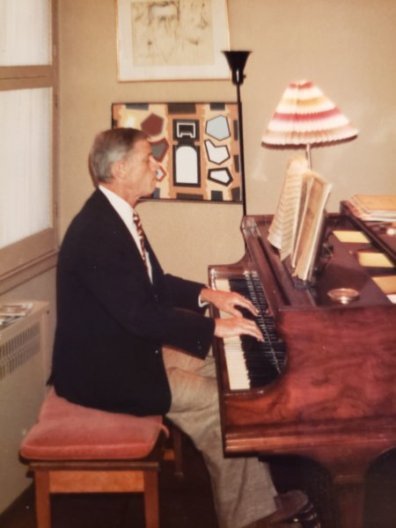

JM playing his Bechstein piano in the NY apartment. Kathe Marshall remembers it "in the northeast corner of an enormous living room (easily 20x40 feet). The photo is a fairly old one because by 1986 the orange tones were not in evidence; and instead 'cool colors' of green/deep fawn/blue/burgundy were dominant." Peter Hooten adds: “Robert Arnold geometric and a Larry Rivers drawing in the background.”

Merrill's grandmother, Mis' Annie, with JM at the Orchard in Southamptom. WUSTL Special Collections.

Introduction: "164 East 72nd Street"

In James Merrill's "A Room at the Heart of Things" (The Inner Room, 1988), an actor studies his lines in an inner space where "the circumference / Grazes the void' (CP 508). This inner/outer contrast prevails within Merrill's New York apartment in "164 East 72nd Street" in A Scattering of Salts (1995, the year of the author's death). He feels secure in the apartment his grandmother has bequeathed him, full of childhood memories and far from the chaos of midtown Manhattan. The ultimate threat to a once safe space occurs in the poem named for Merrill's childhood home, "18 West 11th Street," which was destroyed in 1970 by bomb making domestic terrorists. The poet's peaceful life on 72nd Street seems sheltered from such dramatic violence, yet nevertheless is in danger from "ongoing deterioration"—for example, of the windows that allow in street noises and the sirens and "ruby flares" of ambulances.

In James Merrill: Life and Art, Langdon Hammer writes that Merrill "pored over Gaston Bachelard's Poetics of Space, which describes the house as a 'shell' or 'nest' for poetic reverie" (252). He was drawn to Bachelard because the poet thought of his poems as rooms or houses. He writes in his essay "Acoustical Spaces":

Interior spaces, the shape and correlation of rooms in a house, have always appealed to me. Trying for a blank mind, I catch myself instead revisiting a childhood bedroom on Long Island . . . . fondness for given arrangements might explain how instinctively I took to quatrains, to octaves, and sestets, when I began to write poems. “Stanza” is after all the Italian wordfor room. (CProse 3)

These creative spaces occur throughout his life and art from the cork-lined room in his poem "For Proust" to his homes in Water Street, Athens, and Key West, and particularly the domed room in Stonington where Merrill and David Jackson consulted the Ouija spirits. "164 East 72nd Street" is one of the last of these spaces, though the very last is the hospital room of the unfinished poem he drafted just before his death.

Safe places can still be threatened ones. Bachelard explains that, although a house is a "precarious shelter," the "oneiric house "

. . . apprehended in its dream potentiality, becomes a nest in the world, and we shall live there in complete confidence if, in our dreams, we really participate in the sense of security of our first home. (103)

"164 East 72nd Street" merges the past and present of Merrill's life in childhood memories of his grandmother and his current life with his lover (the actor Peter Hooten) in their shared apartment. The poem is the kind he described as a "shaft sent down into childhood" (Letters 386). Windows are of course the interface between inner and outer spaces, which in "A Room at the Heart of Things" are called "breathing spaces." The theme of the windows is announced in the poem's opening couplet.

These city apartment windows--my grandmother's once--

Must be replaced come Fall at great expense.

Although the expense is worth it, Merrill regrets that nothing in the apartment remains from childhood "except those panes" of glass. One in particular had a "quirk" in the glass that allowed his "Childhood's view"

playing peekaboo with a sylphlike

Quirk in the old glass, making the brickwork

On the street's far (bright) side ripple.

Bachelard analyzes a similar vision in a poet who plays with a window's flaw or "glass cyst":

Here the poet makes images surge up on all sides, he presents us with an atom universe in the process of multiplication. Under his guidance, the dreamer can renew his own world, merely by moving his face. From the miniature of the glass cyst, he can call forth an entire world (157).

Merrill hopes to recover childhood creativity and even innocence as he celebrates his new life with Hooten. (See Reena Sastri's commentary on the poem in James Merrill: Knowing Innocence.) He often used the 72nd St. apartment since his maternal grandmother (see "Annie Hill's Grave" and photo above) left it to him, and it became one of his permanent homes after meeting Hooten and his growing estrangement from David Jackson. Despite their past ("Things done in purple light before we met") they are becoming "Two Upper East Side // Boys again!"

it's impossible not

To feel how adult life, with its storms and follies

Is letting up, leaving me ten years old,

Trustful, inventive, once more good as gold.

Achieving this golden state is a struggle in what the poet describes as an alchemical process, which he explores more fully in Mss. 55, 64 and 65. Developing the gold and silver images of the poem's opening lines, the poem's "gentle alchemist" is needed to order certain "nocturnal scenes" of "brilliant altercations." Hooten's explosive temper is featured in a number of poems in A Scattering of Salts such as "Volcanic Holiday" and "Family Day at Oracle Ranch." Hammer recounts a particular instance when Merrill and Hooten argued over the latter's drinking. Hooten became so angry that Merrill's friend Sandy McClatchy had to take Merrill away for the night (778). Whoever is the "gentle alchemist," a friend like McClatchy, or their couple's therapist Jeanette Aycock, or simply a personification of their own efforts, they have been "Healed by the leaden hand" that can turn their relationship to gold. (See the introduction to "The Sawfish" and the note on Ms. 32 on this site for another source of tension between the two men concerning one of Merrill's friends.)

The poet quotes a memo from the Tenants' Committee that warns of "the ongoing deterioration / Of the widows in our building."* The spelling lapse establishes a link of windows with mortality, and is characteristic of Merrill's love of word play, as in the play on window panes and pains in the second stanza. He describes the window blinds as failing to keep out the light in a line that doesn't quite complete its meaning, ending with an ellipse: "Ruby flares, wherever blinds don't quite . . . " In the image of the "quirk" in the window glass, the rhyme of the line's first and last words reflect the quirkiness: "Quirk in the old glass, making the brickwork / . . . ripple." Literary and musical allusions (the silvery sounds of Léo Delibes' opera Lakmé) support the theme of childhood fantasy. "Reading Sir Walter Scott" is associated for Merrill with the childhood accomplishment of memorizing Scott's poetry to win the prize of an apple (CProse 10), and Through the Looking Glass supports the imagery of windows and the "mirror's drowsy eye," which perceives an alchemical transformation once the "ruby flare" of an argument subsides.

Merrill uses a sonnet like-stanza in Ms. 1., which is a remarkable condensation of the completed poem. Its thirteen lines begin with the first line of the finished sequence and ends with the last one. Yet the tone of the manuscript's final couplet is very different from the finished work:

In the night to come,

Ways of seeing also take their chances,

Ceilings will flush with unheard ambulances.

In the completed poem, the dark invocation of the "night to come" is lightened considerably in the hope that his renewed childhood innocence will "improve his chances" if threatened by a "new spasm." The published poem unfolds in a style which Merrill once described as attempting "ease + lucidity" (Letters 340). Although he seems to have quatrains in mind in some manuscripts (see 2 and 19), he settles on an eight-line stanza that resembles the ottava rima that Merrill admired for its colloquial tone in Byron's Don Juan (CProse 60-61).

Merrill's model might be the original Italian form of an eight-line stanza of eleven syllables. Merrill's meter is a conversational syllabic verse of between ten and twelve or thirteen syllables (as he indicates in Mss. 24 and 39). Each stanza begins with a rhymed couplet in the first two lines and rounds off its roomy structure with a couplet in the last two. Of the eight stanzas, four begin with couplets of near rhyme and four of full rhymes; the couplets of the final lines are all full rhymes. The apartment is "Nine levels above, like Purgatory," where in Dante's poem souls ascend the nine levels toward purification. (As Ms. 88 shows, Merrill lived in apartment 9A of his building.) An allusion completes the poem when Keats's unheard melodies from "Ode to a Nightingale" are invoked in the poem's final two words, "unheard ambulances."

The poem's conclusion confronts the threat that "Juices, blue cornbread, afternoons at the gym" cannot evade. The slip from "window" to "widow" has introduced the theme of mortality, and the imagery of fire engines sounding like "intergalactic gay / Bars in full swing" suggests the threat of AIDS. As the manuscripts show, "East 72nd St." was written in 1989, after Merrill had been diagnosed with the virus and was struggling with the symptoms and treatments. He refers to the HIV virus in the line about the "Uncultured things" done in a "purple light" that "twitched as on a slide." Yet the life inside the 72nd street apartment provides a haven. His lover asks the poet, "Do you ever wonder where you'll," with the unspoken question being one's location when dying. Now in his apartment, he replies "Not here": "Our life is turning into a whole new story." Their careful diets, exercises, "intensive care / For one another," and the easing of the "storms and follies" of adult life, is giving them renewed vitality. Merrill is

counting on this to help, should a new spasm

Wake the gray sleeper, or to improve his chances

When ceilings flush with unheard ambulances.

For the present, the poet is secure in his maternal nest.

_____________________________________________________________

*In his essay "Living in Style: James Merrill with Elizabeth Bishop" (see link on this site), Langdon Hammer writes "The poem was prompted by a memo from the management to apartment owners in the building, including [Bannon] McHenry and Merrill. Dated September 1, 1988, it begins: 'Your board of directors is currently considering options available for dealing with the deteriorating condition of the widows in our building."

Works Cited

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics Of Space. Trans. Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon Press, 1964.

Hammer, Langdon. James Merrill: Life and Art. Knopf, 2015.

__________"Living in Style: James Merrill with Elizabeth Bishop." The Bannon McHenry James Merrill Collection: An Exhibition Vassar College Libraries, 2020.

Merrill, James. Collected Poems. Ed. J. D. McClatchy and Stephen Yenser. New York: Knopf, 2001.

________. Collected Prose. Eds. J. D. McClatchy and Stephen Yenser. New York: Knopf, 2004.

________. A Whole World: Letters from James Merrill. Ed. Langdon Hammer, Stephen Yenser. New York: Knopf, 2021.