Merrill and the Muse: "Letter" and "Syrinx"

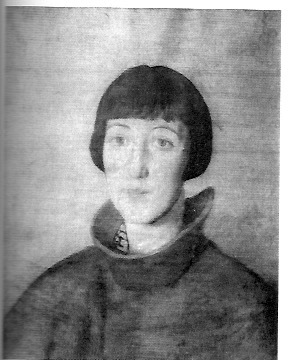

Francis Criss, Portrait of Irma Brandeis © Jean Cook. From David M. Hertz, Eugenio Montale (2013). Painted in 1934 and probably the portrait head mentioned in "Letter" and recalled by Merrill in A Different Person (CProse 606).

Irma Brandeis, James Merrill, Eugenio Montale

Remembering his forty years of friendship with Irma Brandeis, Merrill said it showed him what it was like "to have a muse in one's life" (CProse 370). Brandeis is the inspiration behind Merrill's celebrated poem "Syrinx"; and she is directly addressed in the first version of the poem, entitled "Letter." As Merrill knew, Brandeis was also the Italian poet Eugenio Montale's muse, "Clizia." Clizia or Clytie, like Syrinx, was a nymph in Greek mythology who was transformed through her suffering (see Notes). Brandeis is the woman in numerous poems by Montale, and the one he addressed in his posthumous collection, Lettere a Cliza. Merrill's "Letter," Brandeis' negative reaction to it, and its subsequent recasting, reveals the creative genesis of "Syrinx."

Brandeis introduced herself to Eugenio Montale in Florence in 1933. She was a twenty-eight year old Columbia University graduate student and teacher at Sarah Lawrence College. She remembered it took all her courage to approach Montale. Although he did not win the Nobel Prize for poetry until 1975, he was already a famous poet and director of the library that Brandeis was visiting. She was a scholar of Italian literature who eventually published a distinguished study of Dante, The Ladder of Vision (1962). She loved French and Italian poetry, had published her own poetry and short stories, and admired Montale's first volume of poetry Cuttlefish Bones (1925). Their relationship lasted until 1939, when she, a Jewish American, could no longer visit Italy. Plans to have Montale join her in America fell through since Montale had ties to other women and eventually married.

When Montale's wife died in 1963, Brandeis thought their friendship, if not their love affair, might revive; but as she told Merrill, she decided against writing to him when she heard he might marry his housekeeper (CProse 606). Brandeis disliked any reference to her as Montale's muse or Beatrice figure. A letter to Merrill in 1983 shows she felt violated when a scholar publicly identified her as the Clizia of Montale's poems. However, she discussed Montale's poetry with Merrill when they worked together on translations for a special Montale issue (1962) of the Quarterly Review of Literature, and she didn't mind that, "over the decades" (CProse 605), Merrill understood her former intimacy with Montale. When Merrill thought he had an opportunity to meet Montale, Brandeis replied that he could mention her name if the two poets were alone together (Nov.12 [1960]). But the meeting never took place.

Merrill became friends with Brandeis after she was impressed by the poems he submitted to the Quarterly Review and invited him to interview for a position where she taught at Bard College. Merrill started teaching there in September 1947 and saw her frequently at her home, Casa Minima, near the Bard campus, as well as in New York City and later in Rome. Irma wrote to Jaime (as she usually addressed him) in 1956, recalling a night playing records "years ago [when] you made it quite clear that we were bound in friendship, and the visit sent spinning a thousand heart-eating demons and gave me a new start in life" (Feb. 18). Yet their friendship was often strained by Irma's sensitivity to real or imagined slights when her friend failed to write often enough, or when Jaime seemed cool to her. She was intrigued by his private life as she glimpsed it his poems and in his novel The Seraglio, in which the main character's self-castration disturbed her.

In 1957 she took the risk of asking about "private nuances" in his poetry since she felt it was difficult to see the person through its intricate "fretwork" (Aug. 6). In the same letter she told him that she felt (she was twenty-one years older) like his "natural mother." Possibly this letter provoked one from Merrill that seemed "devastating" to her because she felt he had accused her of "possessiveness" (Oct. 29). Some months later she complained that she couldn't talk to him about one of his poems because "I find the hands-off sign flapping at me whenever I think of you" (Feb. 21, 1958). Such incidents were always resolved, with Merrill assuring her of his continued devotion; but her sensitivity at what she took to be the "distances between us" (Dec. 6, 1976) recurs throughout the letters.

Brandeis could also be critical of Merrill. In 1966 she recommended one of Montale's poems to Merrill because the person addressed in the poem, the Prufrockian character Arsenio, reminded her of Merrill himself. She quoted the first two stanzas in which a woman tells Arsenio "it's time to suspend / that suspension of every worldly illusion," and in the second stanza: "Better the bite of ice than your sleepwalker's / torpor, or late awakening" ("Thrust and Parry, I"). The occasional tensions between Irma and Jaime play into the composition of the "Letter" poem and its later re-conception in "Syrinx." He describes the situation in his "Memorial Tribute to Irma Brandeis" (March 14, 1990). The poem was in part a reaction to news of Irma's failing health in the Sixties, especially the arthritis that made "every movement, every moment" ("Letter") painful. At the same time Merrill remembered "I was going through a bad season myself--the pain less physical than emotional" (CProse 369) during the period of his love affair with Strato Mouflouzélis.

Judging from Merrill's reference to his excursion to Crete in the draft of "Letter," the poem was written in 1966; and "Syrinx" was first published in 1970. Thus the background of heartache in "Syrinx" arose during his relationship with the painter David McIntosh, which is explored in Langdon Hammer's biography (especially Chapter 11,"DMc, 1968-69"). Stephen Yenser observes that Syrinx is the "poet as lover . . . and mourner" (185). She is the speaker of the poem, and through her the poet mourns "his failed struggle to possess" Strato and then David McIntosh (Hammer 466). Yet "Syrinx" also reflects on Irma Brandeis' suffering. As Draft 2 of "Syrinx" shows, Merrill at least begins the poem with Brandeis in mind: "the great god Pain put his lips to her spine / And blew a scale of embers." She is still present in the final version in the image of the flute with its "silvery breath-tarnished tones."

Merrill said that "Letter" described how he and Brandeis were being "transformed by our respective trials" (CProse 369). The poem cites her complaints that "'A flight of stairs is merciless'" and despite medicine and therapy "'Nothing helps.'" Like Brandeis, he feels lost, living "where I do not belong." Montale's poetry may influence the poem. In Montale's "New Stanzas," which Merrill admired for its "mysterious force" (CProse 603), Montale associates Clizia with spirals of smoke, a glass dish, and a chessboard in her Rome apartment. Merrill uses such personal details in the description of Brandeis' New York apartment, with its white bowl, flute (Claude Debussy's Syrinx on the music stand), and flowers on a low table. The image of porcupines in the famous last lines of Montale's "News from Amiata" appears near the end of "Letter" with an allusion to Brandeis' arthritis: "Quills of the electronic porcupine / Whose poison pierces trunk and limbs." (See Brandeis's translation of Montale's poem, which is a poem in the form of a letter.) However, Merrill's allusion to the myth of Orpheus (and to Milton's Lycidas) in describing the severed head "far downstream" is characteristic of his poetic style, and so is the reference to the "fly chorus" of the slaves in Verdi's opera Nabucco (see Notes). Uncharacteristic is Merrill's quoting from personal letters, which may be one reason for Brandeis feeling offended.

After sending the poem to her, instead of the usual praise of his artistry, he read a rebuke that made him feel he had strained their friendship. Merrill then rewrote the poem, "cutting away its perishable tissue of narrative, and leaving only a skeletal trellis of images and feelings. (CProse 370)

Thinking of Irma's flute, and of the nymph who turned into the reeds from which Pan made his pipes, I called it "Syrinx," and Irma's next letter gave out the fragrant balm of full approval. That is what it is like to have a muse in one's life. (370)

In an undated letter after she received "Syrinx," which is likely the one that contains her approval, she tells Merrill of her attempt to "puzzle out the things you are saying darkly," and in particular asks help understanding the poem's equation and square root sign. Nevertheless, she cherishes the poem because "it was begun as a poem for me--thrilling and painful to read." Ironically, she has distanced herself from Merrill's original attempt to share his feelings, and now approves meanings she glimpses only through its intricate fretwork.

Merrill again reflects on the writing of "Letter" in a letter to Brandeis of June 28, 1978. Merrill is assuring her that he did not mean to neglect her and feels no lessening of his affection for her. Yet he also admits that many of his "dear ones" have felt that he has neglected them. As the letter concludes, he writes:

Another ten minutes pass, and ten—twelve?—roll backward. I’ve sent you a poem ("Letter") that I couldn’t possibly find to look at now; but it has offended you in a way that at the time I seem [sic] to understand. Yet at the time I must also have felt that you were rejecting, with it, the no doubt tactlessly-put feeling of oneness with you that had in part dictated it, and for which your beheaded portrait was an emblem. I mean, I too felt that my head and body were on opposite sides of an Ocean in those years. Whatever was worth saving in that poem went into another [“Syrinx] far more oblique poem, which pleased you. I’m wondering now if it wasn’t there that we misread each other’s message? Isn’t that the hell of written words? Enough—

As one can see from the note to David Kalstone on the manuscript of "Letter," Merrill was in fact puzzled by Brandeis' disapproval and asked Kalstone if he could see what might have offended her. Now that "Letter" is available readers can speculate for themselves.

Both "Letter" and "Syrinx" appear with annotations on this site. The annotations of "Syrinx" have been drawn from Stephen Yenser, The Consuming Myth (Cambridge: Harvard U. Pr., 1987) and Langdon Hammer, James Merrill: Life and Art (NY: Knopf, 2015). Readers should consult these books for further analyses of "Syrinx."

Note

References to CProse are to James Merrill, Collected Prose, ed. J. D. McClatchy and Stephen Yenser (New York: Knopf, 2004). Passages from Merrill's letters are quoted courtesy of The Literary Estate of James Merrill at Washington University.

For more information about Brandeis and Montale, see David Michael Hertz, Eugenio Montale: The Fascist Storm, and the Jewish Sunflower (Toronto: U. of Toronto Pr., 2013).