Langdon Hammer on Kalstone and Merrill

From David Kalstone's New York Times obituary, June 17, 1986

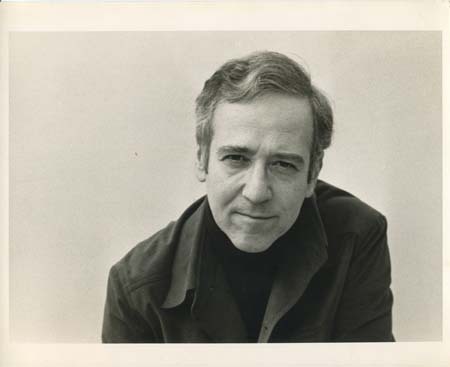

David Kalstone, a literary critic, author and professor of English at Rutgers University, died Saturday at his home in Manhattan. He was 53 years old. A native of McKeesport, Pa., Mr. Kalstone studied on a Fulbright scholarship at Cambridge University before starting his teaching career at Harvard in 1959. He moved to Rutgers in 1967 and lectured there on contemporary poetry and 16th-century literature. Mr. Kalstone was the author of two books, ''Sidney's Poetry'' and ''Five Temperaments,'' the last of which appeared in 1977 and was about the contemporary poets Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, James Merrill, Adrienne Rich and John Ashbery. He was working on a third book, ''Becoming a Poet,'' at the time of his death [published 1989].

Excerpts from Langdon Hammer's James Merrill: Life and Art (New York: Knopf, 2015).

David Kalstone . . .put his name in the guest book [at Merrill's Stonington home]for the first time a year . . . in March 1963. Over the next twenty years, he would stay for long weekends with Merrill and for weekends, weeks, and long summer months when Merrill was in Greece. They’d met by chance on a train in 1962. Kalstone was a junior professor of English at Harvard, where he had studied with Reuben Brower and taught in Brower’s lecture course, “The Interpretation of Literature,” Humanities or “Hum” 6, whose brilliant staff included at one time or another Stanley Cavell, Paul de Man, Anne Ferry, Richard Poirier, William Pritchard, Stephen Orgel, Frank Bidart, and other writers and critics who went on to distinguished academic careers. Brower’s practice of “slow reading” shaped Kalstone’s approach as a poetry critic. Like Merrill, he had little interest in abstract ideas, preferred particulars, and emphasized the role of personal taste in the making and evaluation of literature. His study of Sir Philip Sidney’s poetry appeared in 1965. Already writing on contemporary American poetry, he would become one of the first scholars to write about Merrill’s work, which he did in his book Five Temperaments: Elizabeth Bishop Robert Lowell, James Merrill, Adrienne Rich, John Ashbery (1977). In Merrill, Kalstone found a poet perfectly suited to his training and disposition; in Kalstone, Merrill found his first fully sympathetic commentator.

Yet they were less likely to talk about poetry than about opera, recipes, friends, movies, or sex. David was gay and “a tremendous gossip.” He could be clever and caustic, but was more often sweet, rueful, and considerate. He had grown up in a world quite different from Merrill’s. He was born in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, the first of two sons in an affectionate Jewish family. His father owned a small men’s clothing store; his mother, who had attended college, was a talented painter and taught art. Kalstone went to public high school before Harvard. As a student, he had thick, bottle-bottom glasses, wore regulation academic tweeds, and had a bookworm’s kindly, absentminded air. Merrill took him in hand, and under his influence Kalstone remade his image. He got contact lenses at Merrill’s instigation, and a reliably stylish haircut. He moved to Rutgers, found an apartment in Chelsea, began writing for The New York Review of Books, and became a devotee of the New York City Ballet, attending performances every night at the height of the season. Then came summers in Venice, when he began to dress in Italian suits and sweeping capes, at last as suave in person as on the page— so that Helen Vendler, his friend and colleague from Harvard days, hardly recognized him when they met again. (pp. 343-45)

Hammer explains that the friend addressed in Merrill's " Matinées" is Kalstone:

The bitter truths of “Matinées” are framed by opening and closing sonnets that depict the poet’s first visit to the opera, including Merrill’s pastiche of his younger self’s thank-you note to his host, Mrs. Livingstone (a half-serious tribute to the Southampton matron who welcomed Hellen [Merrill] in her house after the divorce.) The addressee is not a lover but a friend, David Kalstone, the poem’s dedicatee, the “Caro” to whom Merrill was making calls and writing letters throughout the summer. In the ruins of his affair with Strato, with Jackson an ocean away, Kalstone (and the kind of friendship he represented) was becoming more and more important to the poet— and the person— Merrill wanted to be. (pp. 423- 424)

Merrill visited Kalstone in Venice in 1972. Merrill's interview with Kalstone appears in Merrill's Collected Prose.

It piqued his interest that Kalstone had just met Pound in Venice, where Merrill was headed too. Merrill visited DK there in August on his way to Athens. Kalstone followed, and Jimmy, David, and Tony met his ferry on the west coast of Greece. They drove together to Athens, stopping on the way in Yánnina. Merrill wanted another look at the place, and he wanted to show it to Kalstone. Over the winter, he had composed a 136-line poem called “Yánnina,” arising from his visit to the city with Yenser in 1970, and he and DK were at work that summer on an interview focused on the poem. (p. 504)

Merrill also visited Kalstone in Venice in 1972.

Jimmy was staying with David Kalstone, who’d rented a flat on the Dorsoduro side of the bridge. Over the next decade, Kalstone came back to Venice every summer, and Merrill joined him usually for a week or more. They had Venetian routines— a stationer where Merrill bought new notebooks and pens, and a tailor, Cecconi, who created for Merrill a new version of the black suit he’d bought in Venice in 1951 when he saw the premiere of The Rake’s Progress at La Fenice, just a short walk away. (Seeing Kalstone’s matching black Cecconi suit with a scarlet lining, Merrill twinkled: “Priest outside, Cardinal within!”) They might spend the afternoon ogling the male attendants at the extravagantly expensive pool of the Cipriani Hotel on the Lido, dine with John Hohnsbeen and Peggy Guggenheim in her palazzo across the Grand Canal, or, after Negronis at Harry’s Bar, linger among the shadowy strangers cruising “the dark dock.” Venice, recalled Ed White, who was there too that summer, was “still sort of a gay place,” steeped in decadent literary association (Byron, Ruskin, Mann, Proust, Pound, and more). (pp. 538-539).

[Edmund White wrote in Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris (2014) that "I'd been spending several weeks every year in Venice with my best friend, David Kalstone, who lived in ... what we called the molo nero, a “dark dock” for cruising, a pathway between the Piazzetta San Marco and Harry's

Bar . . . ."]

Kalstone's rooms in Venice are described.

. . . he had found dazzling digs in the Palazzo Barbaro. With a fanciful Gothic façade from the fifteenth century and a Baroque addition from 1700, overlooking the Grand Canal just beside the Accademia Bridge, the Barbaro is one of the city’s splendid private houses. In the nineteenth century, it was purchased by Americans, the Curtises, who hosted Boston royalty such as Isabella Stewart Gardner and Charles Eliot Norton, as well as Browning, Whistler, and Monet. The kitchen, which Merrill turned into his study, had once houses. In the nineteenth century, it was purchased by Americans, the Curtises, who hosted Boston royalty such as Isabella Stewart Gardner and Charles Eliot Norton, as well as Browning, Whistler, and Monet. The kitchen, which Merrill turned into his study, had once served John Singer Sargent as a studio. James finished The Aspern Papers while visiting the Curtises, and he used the Barbaro as the model for Milly Theale’s grand, spooky Palazzo Leporelli in The Wings of the Dove. “The wonderful library, into which HJ had his bed moved, had a shelf of his books, all inscribed.” While DK swam laps at the pool and Eleanor went shopping (for her, Robert Morse used to say, Italy was “the shores of Gimmegucci”), Merrill lingered in the palace library with those first editions, marveling at the prose of the Master." (p. 661)

Kalstone's illness:

Kalstone had been rushed to the hospital that March [1985], seriously ill with pneumocystis pneumonia, one of the opportunistic infections associated with AIDS. He was silent about the diagnosis and its implications to all but a handful of his friends. Even Alfred Corn, who took care of Kalstone before he went into the hospital, was left in the dark about the cause: “That seems strange now, but for many people in those days a stigma attached to HIV. I was dimly aware that DK, who never had much romantic success with people like himself, sometimes had casual sex with taxi-drivers or men he met on the street, and given that a single encounter can make you positive, it doesn’t now seem so surprising that David contracted the virus. But at that date it didn’t occur to me that he might have.” Merrill knew what Kalstone was suffering from. He didn’t mention AIDS in his letter to Parigory in April. But he did in a letter to David McIntosh in May. . . . In 1985 such a diagnosis would have been received as a death sentence. The news was “shattering” to Merrill not merely because Kalstone was the first person he knew who had AIDS. DK was his best friend. They’d been sidekicks for over twenty years: the disease could not have struck much closer to home. Merrill felt grief for his friend— and fresh alarm about his own condition. How had Kalstone gotten sick? His speculation that a hospital stay led to his infection expresses ignorance, common in 1985, about transmission of HIV and the disease’s rate of progression. Merrill’s implication is that it could only have been the hospital because Kalstone had avoided casual sex in the two years prior to the onset of his symptoms, the period between infection and the development of “full-blown” AIDS which was believed (mistakenly, as research would show) to be the typical course of the disease.

The idea points to Kalstone’s (and for that matter Merrill’s) need to deny the likely explanation that the virus had been sexually transmitted. “Of all people,” Merrill writes, unable to square the English professor’s sweet manners and refinement with the stereotype of the AIDS patient as a hustler or addict. But as Corn remarked Kalstone’s sexual habits, which were not a secret to his close friends, put him at risk for infection, perhaps not recently but over a longer period. Merrill must have suspected this, and he had to conclude that, if Kalstone had AIDS, he might too. That August, as if to make out that nothing had changed, or precisely in acknowledgment that everything had, Merrill visited Kalstone in Venice bringing Jackson, who made the transatlantic crossing by ship, as in days of yore. Kalstone was in Venice with a student from Rutgers, his new companion. With the two of them, the mediums sat down at the Ouija board in the Palazzo Barbaro. Faced with DK’s diagnosis (by now DJ had been told about it too), they clutched at the spirits. “IT IS A ? OF 6 MONTHS,” George Cotzias reassured them, “WHEN THE FIRST SUBSTANTIAL INOCULATIONS WILL BE READY. IN SWEDEN.” Leaving aside the fact that, for Kalstone, “INOCULATION” would no longer do any good, the doctor wrote a prescription: “MASSIVE POWDERED DOSES OF VITAMIN C. DAILY. FORCE MAXIMUM AVAILABLE IN ANY LARGE PHARMACY. UPON REQUEST + REPEAT: POWDER! + STRONG 2– 3 TEASPOONS + EASIEST TO GET DOWN DISSOLVED IN JUICES. THIS IS A RESISTANCE BUILDER.” But resistance was not a matter of Kalstone’s immune system only: “COURAGE + WILL ARE THE 2 MOST INFLUENTIAL MEDICAL PEOPLE.” (pp. 678-79).

Hammer ellucidates the background of Merrill's two poems for Kalstone.

. . . Kalstone’s condition was worsening. One night at the ballet, David was so ill at intermission that Maxine Groffsky had to call a cab and take him to the hospital. (“ The physical details were pretty awful,” she recalled.) DK was starting to suffer from confusion and memory loss. Another night that winter, Corn went with him “to a night class Grace Schulman was giving about Lowell and Bishop at the YMHA” where he’d been invited to make a presentation. “He said a few words and then fell silent. Grace prompted him with questions. He barely answered and let his sentences trail off into a pregnant silence puzzling to the students. I suggested we bring things to a close and took David home. It was at that point that we decided David shouldn’t go out again.” There would be no more keeping up of appearances. The fact of Kalstone’s illness kept “breaking” on Merrill, he admitted in a letter to McIntosh. Rather than explain any more about his reaction, he enclosed a poem based on a dream “I actually had” that he would dedicate to Kalstone ["Investitute at Cecconi's."]. (p. 691)

Hammer's comment on "Investitute at Cecconi's."

JM’s and DK’s Cecconi suits were a sign of their particular gay style, a sort of team uniform. Now the hour is late, and their tailor is absent, replaced by an “old woman.” Stitching “dawn to dusk,” she suggests Hecate, the tri-form archaic Queen of Night. When she faces the tailor’s three-piece mirror, she turns into the Three Fates, or the witches in Macbeth. She opens “one suspicious inch” of his seam, then thinks better of it. A white robe awaits him, which brings to mind not purity or chastity, but “Oriental mourning,” the white traditionally worn at funerals in China. Over all this looms DK’s “diagnosis.” Sheathed from “throat to ankles” in this robe, is the dreamer protected, insulated from the virus, or enveloped, captured, trapped, like DK? And where did this perilously “heartstopping present” come from? Whose gift is it? The old woman “cackles” like a commedia dell’arte oracle: “Thank your friend […] the Professore!” JM had introduced DK to fine Italian suits, and here he returns the favor. It is an eerie, prophetic poem in which the dreamer recognizes his brotherhood with his dying friend. (p. 692)

Back in New York, on June 1 [1986], Merrill wrote, “Seeing DK yesterday, a figure in a morgue, now + then […] opening his eyes” at the prompting of his nurse, Jacques Francois, who was constantly with him. “Did he even know us, or were his manners living on where his mind could not?” The next day Merrill and Hooten returned: “He knew us, for what that was worth. All but a zombie.” Two weeks later, Kalstone was dead. McClatchy called Merrill, who was in Stonington with Jackson, to tell him the and Art news. Sandy had been there when Kalstone died, with Alfred, Maxine, and David’s brother Charles, a doctor, and his wife Ferne. “They stood around before calling the authorities,” Merrill wrote in his notebook. “Perhaps a last sign of life? Then from outside the room came high uncontrollable sobs. Ferne, perhaps—. She hadn’t wanted to see David at the end. But it was Jacques, locked in the bathroom. He had come to feel part of the family + now he would have to find a new patient.” The stretcher was shrouded, loaded onto a black van, and whisked away past— weirdly— the cameras of a film crew (“ Lights, action!”) who were shooting a movie at the corner diner.

Merrill couldn’t stop sobbing: “sounds I’ve never heard come out of me.” He mourned his friend’s perfect sweetness and the trust it made for: “No quarrel ever. No tension. Pure fun + communion. A 2nd self I could reach by telephone, or walking into the next room.” “Also, GK”— George Cotzias, whom JM had consulted on the board—“ had all but sworn D would recover, only days ago. So that whole source is (again) discredited.” A short obituary from The New York Times, taped into Merrill’s notebook, announced that “David Kalstone is Dead at 53; Author, Critic and Professor.” As was the norm in the paper’s death notices at the time, it made no mention of AIDS. Friends gathered to see the New York City Ballet performance of Mozartiana which Suzanne Farrell dedicated to David just after his death. Kalstone had wanted his ashes scattered in the Grand Canal in view of the Palazzo Barbaro; Groffsky carried out this wish by taking a token amount to Venice (no more, lest she have to explain to the Italian Customs what she was carrying), while Peter brought the surprisingly bulky rest of DK’s “cremains” to Stonington. Merrill had all but avoided Kalstone in his final months; now he coveted what was left of him. He began devising his own burial rites, whether or not they were what others might want, or what David himself did— but then DK had always accepted Jimmy’s plans for him. Merrill and Hooten mixed some ashes in the soil of the plants on the deck. Then Merrill scribbled a quatrain on Venetian notepaper— Beloved friend, the sky + sea of Stonington’s your limit? No: to Heaven fly, to Venice flow. Home-free, home-free. —burned it, and mixed it with more ashes. They borrowed Rollie McKenna’s dinghy, rowed offshore on a “marvelous” day, and, with Jimmy turning the bag inside out below the surface, watched as “a man-sized white cloud” dispersed “in the beautiful sunny water.”

Kalstone had chosen Merrill and Richard Poirier, his colleague in the English Department at Rutgers, as his literary executors. They sorted his letters and notebooks and sent them to the library at Washington University in St. Louis, to rest on the shelf near Merrill’s papers. They also found a draft of a book of criticism about Bishop and her friendships with Moore and Lowell, which Kalstone had left in a rough state. Robert Hemenway painstakingly edited the text, Merrill contributed a coda, and Farrar, Straus and Giroux published the book as Becoming a Poet: Elizabeth Bishop with Marianne Moore and Robert Lowell in 1989— an elegant work of biographical literary criticism and one of the first books about Bishop, setting a direction for future criticism. Meanwhile, translated to the Other World, DK looked forward to another sort of career: he was slated to be reborn in London as “A SPIFFY BOY OF TOP QUALITY. THEY WANT A QUALIFIED (PREPARED?) W O R L D L E A D E R. I WILL BE IN THE FOREFRONT OF SHIELD PROTECTION TO HELP RESTORE THE OZONE LAYER.” But a later séance found him in a different mood. “CARO— WHY ME?” he began plaintively, bringing tears to Jimmy’s eyes. “UNHAPPY TO SEE YOU DISTURBED,” DK went on. “BELIEVE ME THERE IS NO NO NO CAUSE.” Sounding less like his gentle old self than an ACT UP protester, he explained that he’d been “THE VICTIM OF BIG CITY MEDICINE” and “THE CONSPIRACY TO KILL US ALL,” meaning gay men. “THE VICTIMS OF THIS CALLOUSNESS MORE OFTEN THAN NOT CRUMBLE IN DISPAIR + INDIFFERENCE AS I DID.”

Kalstone’s memorial service was held on September 20 in the New York Public Library. It was a decidedly high-culture event attended by “300 or more.” The soprano Dawn Upshaw, a rising star of New York music, sang a setting of Milton by Charles Ives, Purcell’s “Music for a While” (text by Dryden), and a Mahler song. McClatchy welcomed the guests and read from Stevens. Poirier recalled Kalstone as a student of Reuben Brower. (pp. 709-711) Charles Kalstone spoke for the family, Groffsky spoke of David’s love of the ballet and Venice, and Corn read a paragraph from Kalstone on Bishop’s late poem, “Poem,” and then the Bishop poem itself. The longest statement was by Edmund White, who evoked DK as “a master of the art of the telephone call.”

Like Mme de Sévigné, who could plunge headlong into a story in the first line of a letter, David would sometimes start off by singing the latest pop song or quoting the latest advertising jingle. Sometimes he’d pretend to be someone else. I’d have a mad Russian professor on the end of the line asking me indignantly how to join the New York Institute for the Humanities and denouncing all other Eastern Europeans as frauds and KGB agents; or a timid, high little voice would be saying, “Hello, Mr. White, I’m twelve years old and I’ve just read your Joy of Gay Sex.

Merrill concluded the program by describing the scattering of DK’s ashes in Venice and Stonington. He read an elegy for Kalstone by Mona Van Duyn, Sidney’s translation of the 23rd Psalm once again, and a lyric paragraph from Kalstone's diary:

Tonight, standing in the Barbaro window, I think must be the most beautiful night in the world. Cool. Soft vanishing sunlight and slow shadows on the Grand Canal. One deep sun spot. Being alone. Oh, to open my heart as I have not for years— Venice, my beautiful Venice. The heart aches as the light passes. The town is full of beacons, each with its own hour— I have never known it so beguiling as this summer— the lightning and hail of the other evening … Oh, never not to return!

Not surprisingly, given the pious conventions of public memorials and the depth of his friends’ grief, little was said about Kalstone’s illness, and only White, referring to the title of his own popular book, used the words “gay” and “sex.” It was as if Kalstone had not died but evanesced, like that summer light in Venice. But of course there was more to reckon with. Several poet friends of Kalstone wrote elegies for him, in addition to Van Duyn’s: Corn, McClatchy, Henri Cole, Anthony Hecht, Richard Howard, and Adrienne Rich. Elegies for David Kalstone— they were virtually a subgenre in the suddenly and sadly vital genre of AIDS elegy. For all of his talks with the dead, Merrill seldom wrote conventional elegies but he did on this occasion. The subject and the Sapphic meter he chose for it make “Farewell Performance,” inscribed “for DK,” a companion piece to “Investiture at Cecconi’s.” It is a poised, exquisite, ceremonial poem that might have been read at Kalstone’s memorial service without changing the tone. But it is also more personal and dark than anything that was said that afternoon. (709-12)

[Kalstone's assocciation with the New York Ballet, which is celebrated (and mourned) in "Farewell Performance," is first mentioned on p 644: "Kalstone, the balletomane, took Jimmy to a party for George Balanchine’s prima ballerina, Suzanne Farrell."]

Hammer's analysis of "Farewell Performance."

“Farewell Performance” is about sublimation and de-sublimation, art and AIDS. It begins in the seats of the New York State Theater with a memory of the performance Farrell dedicated to Kalstone. [The two opening stanzas are quoted. “Art. It cures affliction.” Merrill can only take this truism seriously by forgetting about his subject. But that is just the cure art offers— a temporary forgetting. In the middle of the poem, Merrill faces up to the fact that Kalstone’s life is over. [Ten lines are quoted.] “You’d caught like a cold their airy / lust for essence.” Merrill is speaking about what is most high-minded in his friend. The dancers reach for the timeless and immaterial, and the audience share in that contagious idealism.

If it can be “caught like a cold,” however, art is perhaps less like a cure than a cause of affliction. In his drafts, Merrill had “taken on” instead of “caught” and “rage” instead of “lust”— easier words. But he wanted to bring up the sexually transmitted infection that led to DK’s death. Merrill is suggesting that art not only fails to save us; it may not be good for us. And “essence” adds a further twist. In personal columns and pornography, the word was a code advertising black men and women through an allusion to Essence, the magazine for African Americans that began publishing in the 1970s. The phrase “airy lust for essence” (“ airy” in the sense of unconsidered) plays with that slang to tweak Kalstone about his sexual tastes and choices. The dig gives us a glimpse of the barbed byplay that was an ingredient in Merrill’s friendship with him; it is a small, semiprivate reference, a comment readers are meant positively not to notice. But Merrill tucked it into the poem with a point to make: that DK’s sexual history, no less than his ballet subscription, was part of his "gruel of selfhood." (pp. 712-713)

. . . . Merrill’s choice not to use the word “AIDS” in a poem is significant. More than discretion, it was a choice not to use the vocabulary of public debate, for the same reasons he’d rejected the phrase “the sickness of our time” in “An Urban Convalescence.” The language Merrill found to write about AIDS was figurative and semiprivate, paradoxical and ambivalent, and powerful and resonant because of it.

In “Farewell Performance,” we see that ambivalence in Merrill’s shifting relation to DK. Merrill is the audience and Kalstone the performer as JM releases his friend’s ashes into the sea and they cohere in “one last jeté” before dissolving into darkness. With relief, the poet seems to accept his friend’s death as Peter’s “sun-warm” hand clasps his wet one. The gesture recalls Merrill to life, drying and warming the hand that delivered his friend’s remains into the underworld. But it’s not easy to let go of the dead, and the question of Merrill’s relationship to Kalstone returns with the dancers’ return to the stage. [Two sanzas are quoted.] The dancers are simply “they”: a pronoun that gives them an indistinct, spectral quality, allowing them to float free of personality and gender, even as Merrill stresses their physicality. They are “sweat-soldered” when they return to the stage, fused by glistening traces of the “sea-change” that was their performance: radiant bodies, bonded, seeming to defeat time and materiality. Yet, as Merrill comes “up close,” “their magic / self-destructs.” Their magic is dispelled by the same force, the body, that created it (pp. 713-14).

Merrill worked hard to get these last lines right. Showing drafts to Hooten, Yenser, Van Duyn, Corn, and McClatchy, he sought more help than usual. When McClatchy wrote back with queries about the last stanza, Merrill explained that he had introduced “dripping” to link the dancers to DK. "Is it too creepy?" he wondered. “The strongest implication I see is that the dancers were somehow with him as he vanished underwater.” He hoped the detail clarified their “odd complicity.” But “complicity” in what? In the last line of the new draft he sent with this letter, the dancers “beg our forgiveness.” But forgiveness for what precisely? Where was there injury or wrongdoing? He gave a further gloss to Yenser, who asked about the same lines. Referring to the dancers and DK, Merrill said he wanted a sense

of their having nearly saved him— like lifeguards— or as art can save our souls over and over, but not our bodies. There’s the “rage for essence” too, which (says my conceit) infected DK, made him and us perhaps think that death was graceful and beautiful as a dance. But au fond, of course, that’s not really so, and they must be forgiven for implanting the notion. Can the lines bear all these meanings? Would they be better without some of them? Can they be separated???? (pp. 714-15).

No, they couldn’t be. Merrill added further weight and complication by using “self-destructs” in the final text. It suggests that the magic of the dance carries with it a wish for death that the dancers and their audience share. Art not only can’t save us; we don’t necessarily want it to. When we “lust for essence,” we want transcendence, to go beyond the body, perhaps even to destroy it. This is the definition of the sublime— a tradition Merrill invokes when the dancers return “pale” and “dripping.” Along with his choice to write in Sapphics, those words recall Sappho’s second ode, the most famous lyric of same-sex desire and one of Longinus’s examples of the sublime. Merrill annotated the ancient Greek fragment as a student at Amherst, and he had his college textbook on the shelf in Stonington with his translations in pencil as he worked up Sappho’s stanza and meter. The ode breaks off as passion leaves the poet sweating and trembling, only “a little short of death.”

Merrill and Kalstone had lived the same sort of life. Now, Jimmy feared, they would die the same death. (p. 715)

The index entries for Kalstone in Hammer's biography.

Kalstone, David, frw. 1, 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, 9.1, 9.2, 9.3, 9.4, 9.5, 9.6, 10.1, 10.2, 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, 11.1, 12.1, 12.2, 12.3, 12.4, 12.5, 12.6, 12.7, 12.8, 13.1, 13.2, 13.3, 13.4, 13.5, 14.1, 14.2, 15.1, 15.2, 15.3, 15.4, 15.5, 15.6, 15.7, 15.8, 16.1, 16.2, 16.3, Hammer, Langdon (2015-04-14). James Merrill: Life and Art . Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.