Kathleen Bonann Marshall's Description of the 72nd Street Apartment

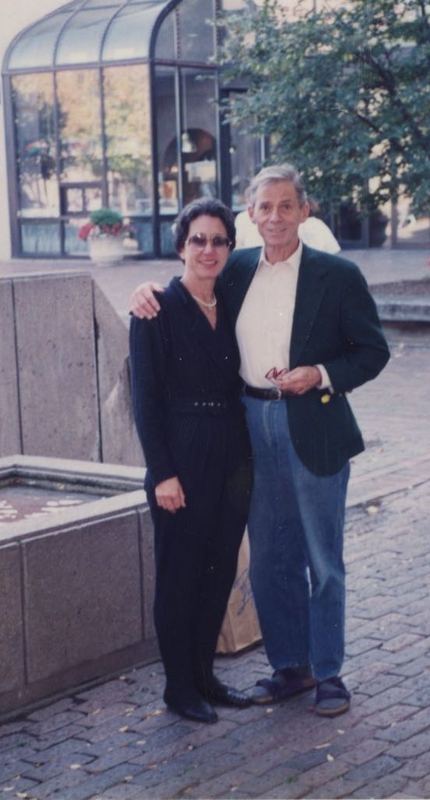

Kathleen Bonann Marshall and James Merrill (Iowa City, October 1992, when Merrill gave a poetry reading at the University of Iowa).

A Description of James Merrill's East 72 Street apartment from Kathleen Bonann Marshall's Dear Premises: James Merrill and the Domestic Impulse in his Life and Work (UCLA eScholarship, 2018).

ABSTRACT

Dear Premises is an unusual close personal look at the poet James Merrill through his 20 years of interactions and correspondence with a family with whom he had a long intimate relationship.

Part I includes an analysis of traditional artistic and intellectual elements that can be traced through Merrill’s early works in poetry, fiction, and drama with an emphasis on influential sources in Continental and American literature. His verbal skill with strict metrical forms, subtle illusions, and elaborate word play unites with his own experiments in prose, two works of drama and two of fiction, to produce the poet’s growing achievements in maturity of dialog, narrative sequence and, characterization. The unity of focus in all his early work exhibits a passionate thematic devotion to the artistic and personal dilemma of his social position as it emerges into the freer, looser landscape of modern life. Part II offers five special examples of Merrill’s casual, gentle, and generous behavior in a domestic setting of some chaos and complication. The letters, which cover years between 1974 and 1995, permit the reader to follow both Merrill and the family through their increasing intimacy in a shared personal universe and are included as a separate media attachment. Part III synthesizes these personal and idiosyncratic and epistolary occasions into a broad view of the poet James Merrill as an important cultural icon for redemptive power of the human experience and of love.

EXCERPT

Days of 1986

164 E. 72nd Street in New York City

After he had spent several days in the cocoon of our modest Iowa City household, James was eager to share his own NYC Coop apartment with us. Shocked that I had never spent time in Manhattan, he encouraged us to consider a week or more on the Upper East Side in the apartment which originally belonged to his maternal grandmother, passing to his mother and then to himself after a second marriage made Atlanta his mother’s permanent home. Seeing other people’s houses can be surprising, occasionally reinforcing observations made about that person which now extended through rooms reflecting what one had concluded already, what one had imagined, and what had been carefully hidden from view.

Our ride up to the ninth floor at 72nd Street accompanied by an experienced liveried doorman, was fascinating for our 3 and 5 year olds. They had never heard of nor seen a special elevator cage for deliveries—of which our luggage constituted an important category. Trying to explain the niceties of a service elevator to small children can be challenging. But as soon as the apartment door opened, all the puzzlement was forgotten. Here just inside was a charming span: a room which in another era would have served as a vestibule or small parlor was instead the very centerpiece of the apartment. We stepped into a large square room lacquered dark green with a very ornate mirror on the wall, and a formal mahogany dining room suite arranged on a beautiful oriental carpet. This room was peacefully resting between meals or Ouija sessions, so we proceeded into the enormous living room—finally a space, I thought to myself, equal to its name, since according to James a great deal of living could go on simultaneously in it. The room’s proportions were sufficiently spacious that one could easily imagine a gathering of 50 guests comfortably chatting in groups, examining the walls of books, exploring the backgammon table, urging an adept to try the beautiful piano standing grandly in one corner. A pair of female decorator friends had recently taken JM and DJ in hand to provide a softer and more comfortable atmosphere for their parties in this apartment, and it was handsome indeed.

A butler’s pantry led off to one side of the living room and into a well-equipped modern kitchen. Other doors led to a guest room/study and to the master bedroom which shared a spacious tiled bathroom with the guest room. Our children were already dashing about with awe and curiosity: “Uncle James has an enormous mountain of pennies on the dresser next his bed, Mommy.” In the guest room/study where the children would sleep, twin beds were pushed into a seating arrangement against the walls. And the center table—low, large, round—was covered with camera equipment of an obviously serious, expensive sort. As it turns out, the camera, lenses, film, and swag bag belonged to well-known photographer Rollie McKenna. (She must have been very certain indeed of the safety of the Merrill apartment!) Also in this light, bright room was a desk scattered with pages that it took an elaborate explanation to convince the children were to be admired but not moved. Above the writing surface was a poster and newspaper clippings announcing James’s recent appointment as Poet Laureate of Connecticut. I did not know and sat down to add my own note saying how glad, “how well deserved.” Below me on the floor, my son was arranging his plastic Heman and Strato figures from a popular cartoon series into military array. Much later, on our way out of NYC and over the bridge, Zach would glance behind us and call softly, “bye, Strato,” sharing in a gentle voice that Uncle James didn’t have any toys of his own. So, Zach left Strato as a playmate tucked into his bed. The wonderful and funny letter from James that arrived at our home a month later said it all in JM’s usual playful style.

Everywhere one turned in that apartment there were kind little notes: some in James’s hand and some left by Mona Van Duyn, who had been a recent visitor to the apartment with her husband, Jarvis Thurston. Here and there were suggestions to help us find a few indispensable things like the TV [so well-hidden that we might have been several days discovering it] and the garbage chute back along the corridor of servants and service rooms. Our host had, with his usual thoughtfulness, provided names in the building of families who might have nannies to share of an evening. He had thought of everything a young family might need: pointing out the nearest green grocery, pharmacy, and a carrousel in Central Park which became a daily destination for our children. One could sit down in a chair with tea cup in hand and find instantly at right or left a cocktail square of needlepoint to cushion the wood furniture from dampness. Reading lights were placed where reading would most likely be done. Chairs were grouped for intimacy but could easily be turned into a larger, more open and welcoming circle. The living room was sober in hues of purple, brown, and green woven fabric in a fine old-fashioned print. In survey, I could see the apartment as having been slowly and carefully adapted by James from items belonging to his family (perhaps for generations) into a gracious, modern palate of color and style much more 1980’s than 1930’s--and very much his own. The Oriental rug spread underneath it all unified the space into little less than a magic carpet ride for me.

I could not help myself in private moments from running my fingers over an obviously well-worn set of Proust or a piece of Murano blown glass. Every surface held an object that I’d like to know the origin of and its value to the owner; propped among the books for all to admire were drawings, some impromptu on envelopes and others quite wonderful finished sketches that would take hours to examine and understand. But James was in China; and I was in fairyland permitted to make up stories about objects that intrigued me. (This was very good preparation for the summers I spent in Stonington after James’s death where, given a key to and freedom to explore the Water Street flat any way I chose, I could make connections to objects he most valued.) I saw immediately as we settled into this lovely New York City apartment that our host, though now at a distance on his trip to Japan and China, had considered every detail for the comfort of his fortunate guest, exemplified his promise from “A Tenancy” in Water Street:

If I am host at last

It is of little more than my own past

May others be at home in it.