Mirror Image: "The Thousand and Second Night"

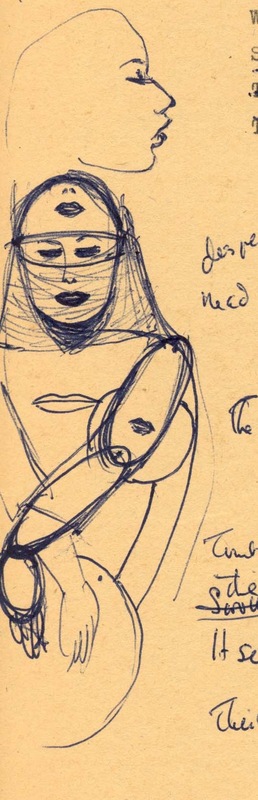

Merrill's sketch from Manuscript 6 of "'Rigor Vitae': Hagia Sophia"

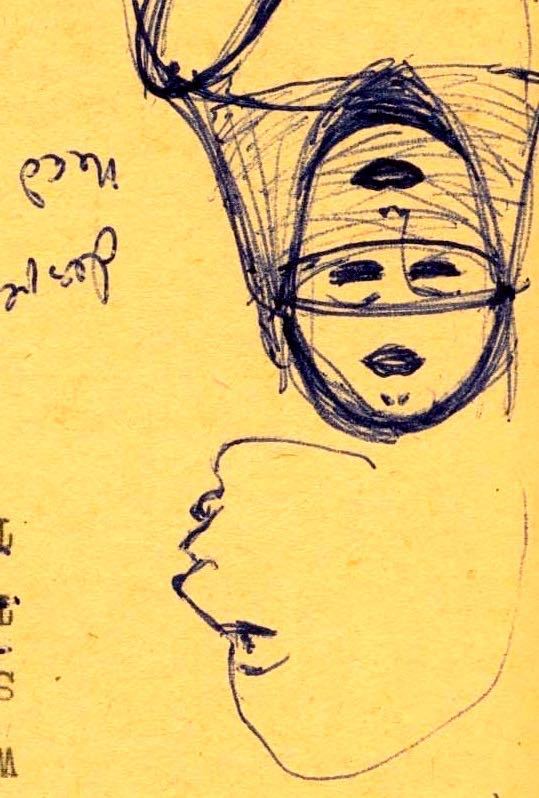

Merrill's sketch from Manuscript 6 of "'Rigor Vitae': Hagia Sophia" when turned upside down.

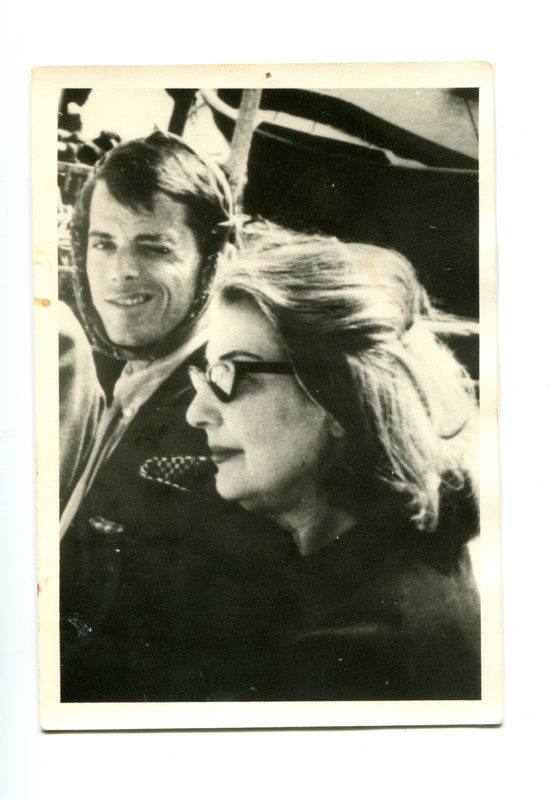

Maria Mitsotaki and James Merrill, afflicted with Bell's Palsy. WUSTL.

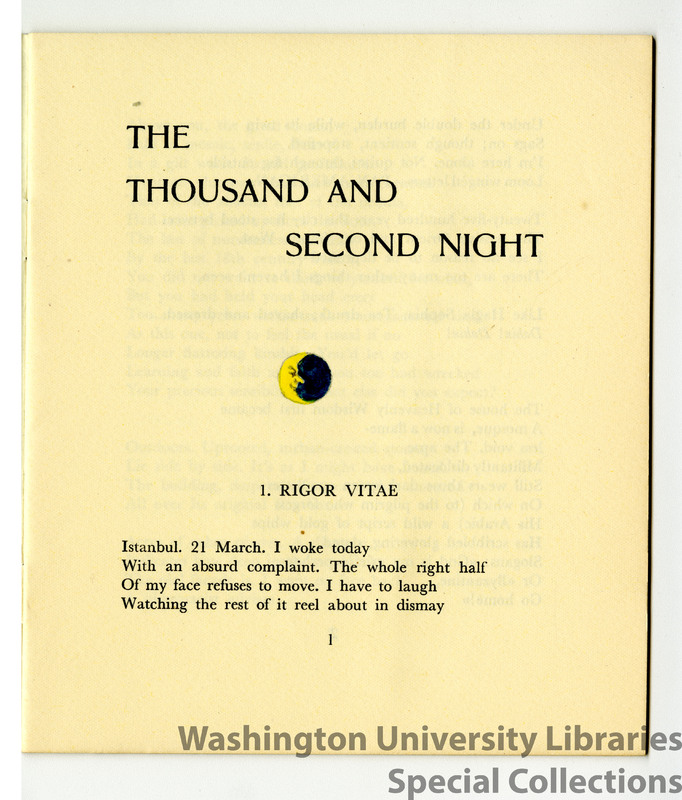

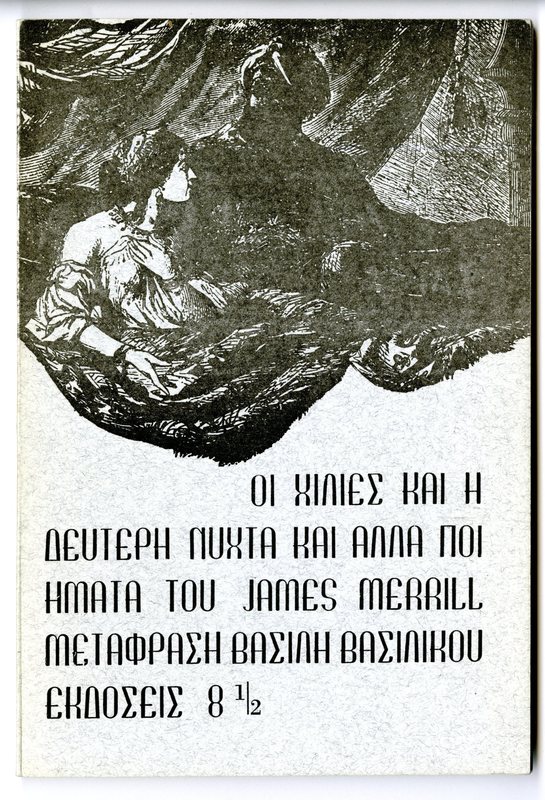

Hoi chilies kai e meutera nuchta (The Thousand and Second Night and Other Poems), trans. Vassili Vassilikos. [Athens:] Ekmoseis 8 1/2, 1966. Cover art unidentified. WUSTL.

NOTE

The 157 manuscripts for "The Thousand and Second Night" (many double-sided) are far more numerous than those for the other poems on this website. Moreover, the sheaf of manuscripts Merrill sent to Washington University's archive does not appear in any obvious chronological or sequential order, and many repeat the same text with only minor changes. For these reasons, this site does not include all of the manuscript pages and does not follow the sequence they were in when sent to the archive. To show how these manuscripts develop into the finished long poem, the manuscripts are organized according to the various sections of the poem, including the five numbered parts and subdivisions within them. This arrangement allows the reader to view the development of each part of the poem. Merrill's comments throughout the manuscripts allow many insights into the poem, including its final scene between Scheherazade and the Sultan.

The following introduction draws on Merrill's manuscript comments, and links to individual sections of manuscripts in the left margin contain additional information. In the following, WUSTL refers to Special Collections, Washington University Libraries, and Yenser and Hammer to: Langdon Hammer, James Merrill: Life and Art, Knopf, 2015; and Stephen Yenser, The Consuming Myth: The Work of James Merrill, Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1987.

INTRODUCTION: Mirror Image: "The Thousand and Second Night"

In manuscript 1 of "Merrill's Notes" (left margin), Merrill described "The Thousand and Second Night" as a kind of verse notebook or journal . . . kept over nearly a year." The poem's opening lines are a journal entry: "Istanbul. 21 March. I woke today / With an absurd complaint. The whole right half / Of my face refuses to move." Merrill suffered this facial paralysis in 1962 and considered it a symptom of his depressed condition at the time. He described the affliction to Irma Brandeis, to whom he dedicated the poem: "half of my face was paralyzed, my lower lid sagged . . . . it turned out to be a common local complaint." (The illness is known as Bell's Palsy.) Merrill soon responded to treatment but told Brandeis "it did give me a turn. A crack in the Mirror of the Soul . . . ." (Letter to Brandeis, April 12, 1962, WUSTL).

Reflecting on his life and loves in prep school and college, Merrill wrote in his January 29, 1948 journal of the "chief duality" of his nature, arising from "the concept of Friend & and the concept of Lover" (WUSTL). The notebook form of the poem, with each part allowing fresh perspectives on the narrator's condition, is ideal for exploring this crack or flaw in his character. The opening of the "Carnivals" section of the poem recalls the poet's early conflicts when discovering his same-sex feelings. The scene is dinner with an old school friend whom he once loved passionately. He recalls an evening walk with him in fall 1943 when "to die in [his] presence seemed the highest good." This conflict appears when his friend's wife says that they must stay friends, and he thinks "I had a herd / Of friends. I wanted love, if love's the word / On the foxed page of the long-mislaid book." The mislaid book is perhaps the journal he mentions a few lines earlier

I have kept somewhere a page

Written to myself at sixteen to my self at twice

[that age,

Whom I accuse of having become the vainFlippant unfeeling monster I now am—

Instead of love, he has experienced a thousand and one nights of "grotesque" sensations: "Stripping the blubber from my catch. I lit / the oil-soaked wick, then could not see by it." In manuscript 6 of "Carnivals," which describes meeting his school friend in New York ("Sam and his new 3rd wife"), the blubber is the sordid result of his "early hunts for love." Still more grotesque images follow in the "Postcards from Hamburg, Circa 1912" section of "Carnivals." After the death of his Great Uncle, the narrator's Aunt finds the postcards, including one of "a sepia-dim / Shamelessness from nun's coif to spike heels." Although the cards speak to the narrator of hidden shames, he secretly keeps some to "spend the night rekindling with expert / Fingers—but that phase needn't be discussed . . . ."

The "Carnivals" section of the poem describes the split in the traditional terms of the flesh and the spirit. The word carnival appears in both the usual sense of a festival (e.g. Rio de Janiero) and its etymological sense (as in manuscript 8) from Medieval Latin, carne vale, "flesh, farewell." Although the narrator exaggerates his failings, he supplies many examples of them. He feels indifferent to the beauty of Hagia Sophia and the "humane splendor" of the Parthenon, admitting that he has "wrecked [his] precious sensibility;" his visit to a Turkish Hamam encloses him in a "lean tomb; he admits in "The Cure" that he was less than "human" to the truck driver who was his lover. Most of all, he is shamed by his image in the eyes of three old friends in "Carnivals," who tell him he has changed for the worse. (The real life identities of the friends are indicated in Manuscript 2 of "Carnivals.") Imagining the figure of death in the Rio de Janiero carnival, he thinks:

the dog-brown eyes

In the chalk face that stiffens as it dries

Pierce you with the eyes of those three friends.

The narrator has been trapped within the dichotomy of flesh and spirit. However, one of the prose passages included in the poem suggests a way to face the dilemma.

The soul, which in infancy could not be told from the body, came with age to resemble a body one no longer had, whose transports were far beyond what passes, now, for sensation. All irony aside, the libertine was "in search of his soul"; nightly he labored to regain those firelit lodgings . . .

If the libertine is indeed in search of his soul, one might at least hope that the soul / body split might be resolved. In the same manuscript ("Merrill's Notes," 1) that describes the poem as a verse notebook, Merrill describes a "theme" of the poem as "a struggle against dialectic—if one of the glories then also one of the most crippling aspects of human thought, viewing things as antagonistic opposites like Art and Reality, Spirit and Body. The symbolic voyage and active travel experiences."

The hope of escaping these crippling dichotomies emerges through "travel experiences," or a spiritual journey. Manuscript 1 of part 4, the classroom scene, contains the opposing phrases "objects of desire" and "love without an object." Manuscript 3 notes the poem's "gradual mellowing of a viewpoint - the long wait for this - REBIRTH." The poet's hope of reconciling flesh and spirit is seen in the religious allusions that appear throughout the manuscripts but are only suggested in the poem. For example, in the "Epigraphs" section, manuscript 3 alludes to the book of Job: "yet in my flesh shall I see God" (19:26). In manuscript 1 of "Postcards from Hamburg," Merrill cites Christ's words at the Last supper: "The orgy: 'This is my body. Eat this'" (Luke 22:19)." An "orgy" suggests the libertine's labor to restore the "firelit lodgings" where soul and body are united, but also the classical sense of orgia as a sacred rite. Consuming Christ's body and blood in the Christian communion service is a both a sensual and spiritual experience.

As in manuscript 1 of part 4, a philosophical term that appears frequently in the manuscripts is "love without an object" (see also manuscript 20 in the "Love. Warmth" section). The concept is found in many philosophical and mystical traditions, and in the Persian poet Rumi: “A love with no object is a true love." (See the "Related Verses link.) When the narrator in "Carnivals" speaks of the man he loved in his youth, "To die in whose presence seemed the highest good," he is imagining an unselfish love that need not possess the object and escapes duality. A similar ideal appears in the narrator's memory of his grandmother's love in the prose section of part 1.

Although Merrill wishes to affirm the power of such love, he is "suspicious of his own rhetorical powers, his too-easy wish for a simple, decent, sunlit solution . . . " (Hammer 326). Back home after his travels, the poet writes:

Love. Warmth. Fist of sunlight

Pounding emphatic on the gulf. High wails

From your white ship: The heart prevails!

Affirm it! Simple decency rides the blast! —

Phrases that quick to smell blood, lurk like sharks

Within a style's transparent lights and darks.

High-flown phrases such as "The heart prevails" are easily undercut and, as Stephen Yenser observes, "since 'Love' has sprung from the memory of desire" these lines "also allude to masturbation" (133). The reference to self-love undermines the affirmation of love without an object. However, the ideal of unselfish love has been formulated, if only by its current absence from the narrator's life. The poet has learned from his past affairs:

Lost friends, my long ago

Voyages, I bless you for sore

Limbs and mouth kissed, face bronzed and lined . . . .

In the form of a classroom discussion of the poem, Part 4 defends the claim that the poet is "affirmative," but only in his attempt to give form to chaotic experiences. To a question about the poet, "Did he 'affirm'?" the teacher answers, "Why, constantly. And how else / But in the form. Form's what affirms." The shaping of the experiences may affirm the poet's quest to reconcile flesh and spirit, even though it can have no direct effect on achieving it. Instead, the poet imagines a vision of this reconciliation through the symbolic figures of Scheherazade and the Sultan.

The long deferred appearance of Scheherazade, teller of the thousand and one tales, concludes the poem. Her nightly fictions enchant the Sultan, defer the usual fate of the Sultan's former wives, and achieve a reconciliation on the thousand and second night. Representing the soul, Scheherazade addresses the Sultan as his "servant"; the Sultan replies that he is her "slave." Although the soul and senses are separate, their interdependence is understood.

They wept, then tenderly embraced and went

Their ways. She and her fictions soon were one.

The Sultan is like "the poet at the beginning, who is also alone, waking, in the Orient, and divided from himself" (Yenser 136).

He slept through moonset, woke in blinding sun,

Too late to question what the tale had meant.

Yet in the embrace of Scheherazade and the Sultan, and the unification of the teller with her tales, the soul's mirror image appears whole again. In Manuscript 7 of "Postcards from Hamburg," Merrill comments on these final sixteen lines of the poem:

What makes 'The 1002nd Night'* beautiful is that it respects the emotions - respects both the 'low' and the 'high' as imbued with poetry, courtesy, sadness. How grateful I am for it. *last 16 lines.

Scheherazade's embrace of the Sultan does not end the dialectic movement between them. Yet Merrill's statement of gratitude for the beauty he sees in the final quatrains implies a possible reconciliation through love, or at least "courtesy," between the soul and the senses, the high and the low. This vision represents the ideal of love throughout his poetry.