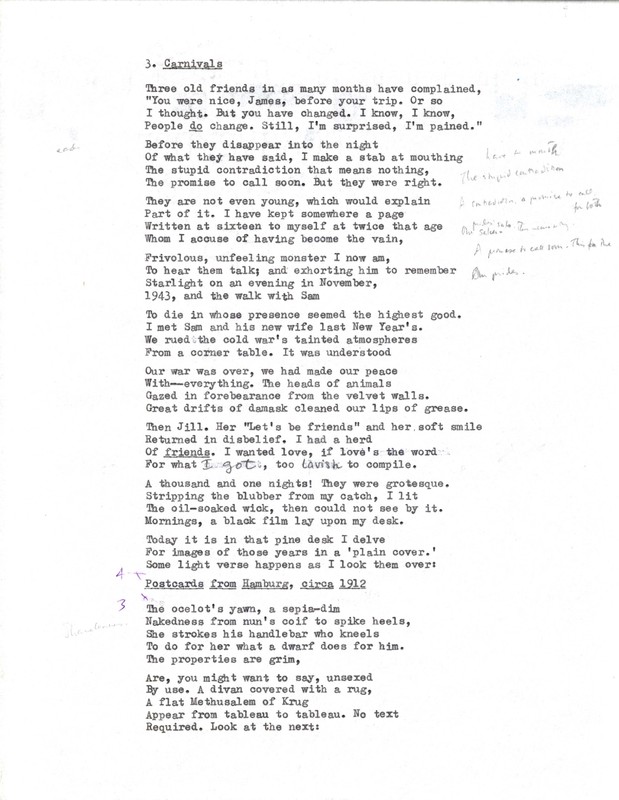

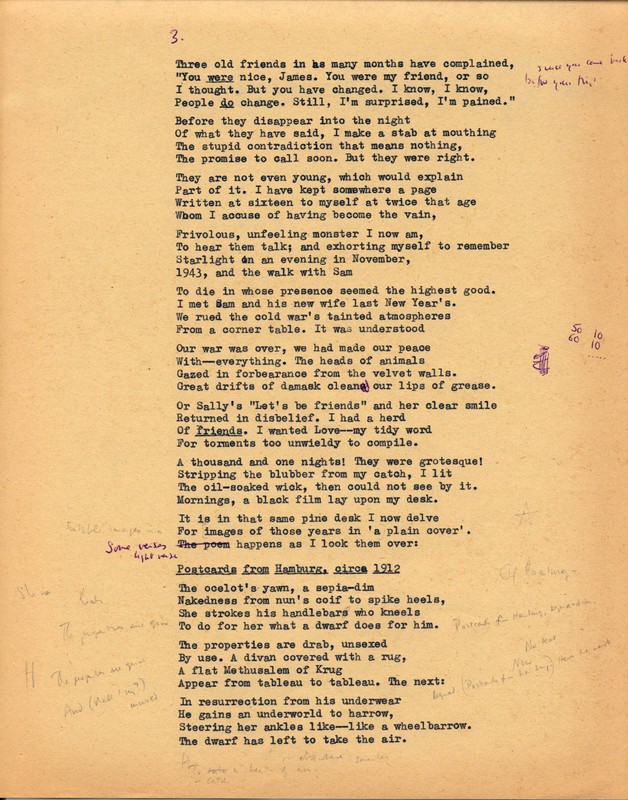

"3 / Carnivals"

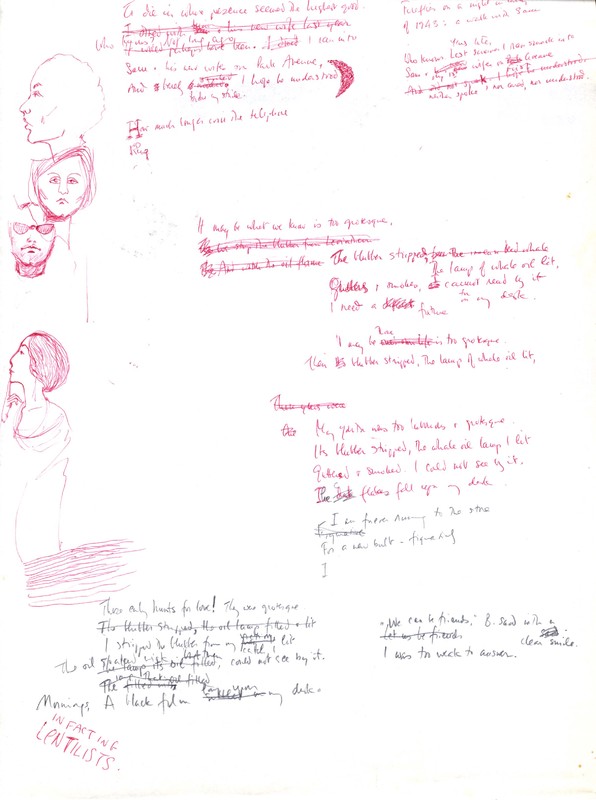

1) "To die in whose presence." Ink, pencil. Four sketches

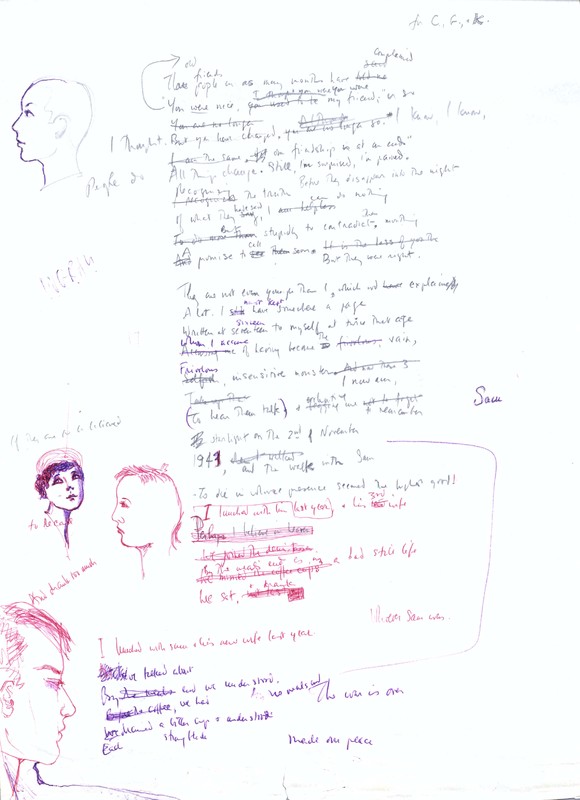

2) "For C, F. & K. Three people [old friends] in as many months." Ink, pencil. Four sketches.

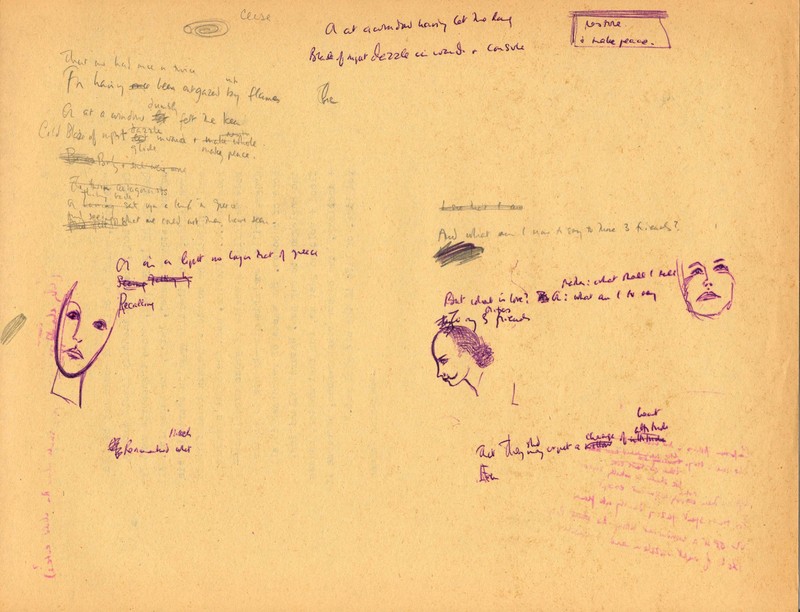

3) "That one had once or twice." Ink, pencil, draft paper. Three sketches.

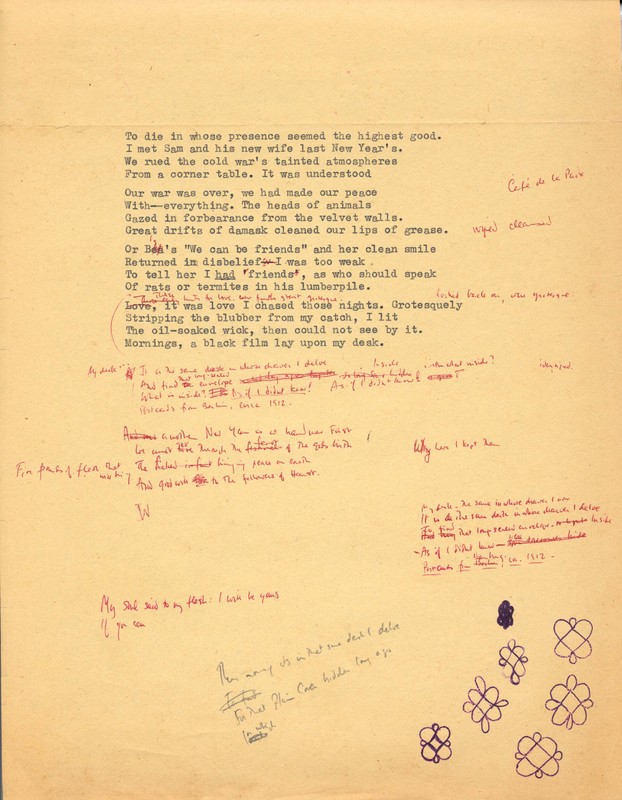

4) "To die in whose presence." Ink, draft paper.

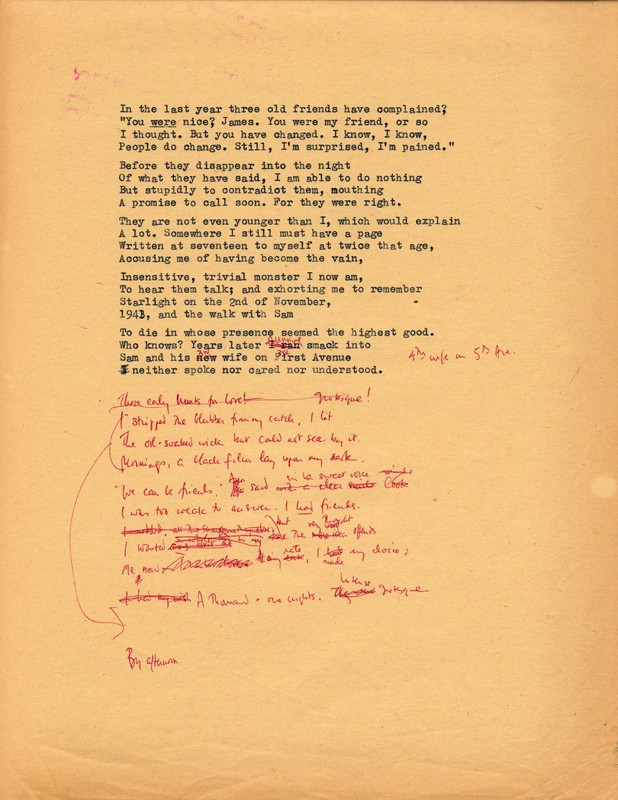

6) "In the last year three old friends." Ink, draft paper.

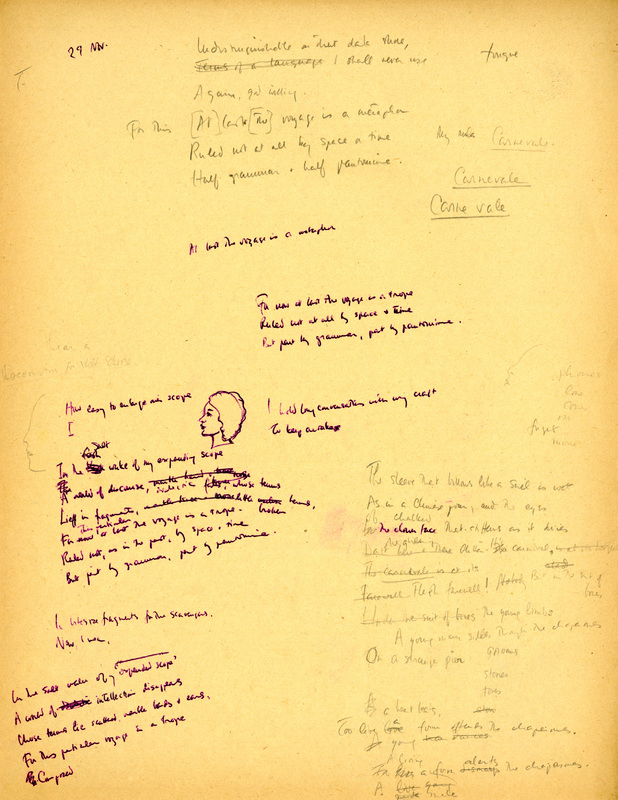

8) "29 Nov. Indistinguishable on that [word] shore . . . . Carne vale." Ink, pencil, draft paper. One sketch.

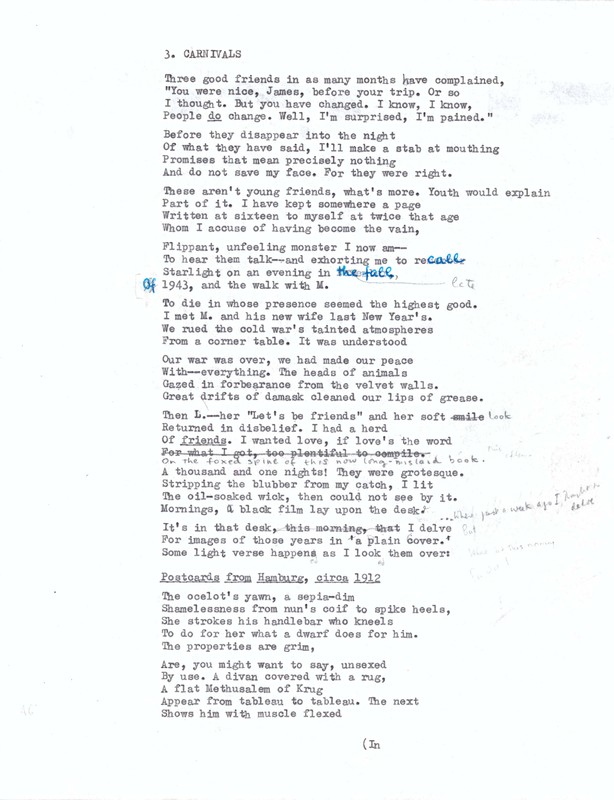

9) "3. CARNIVALS. Three good friends." Ink, pencil.

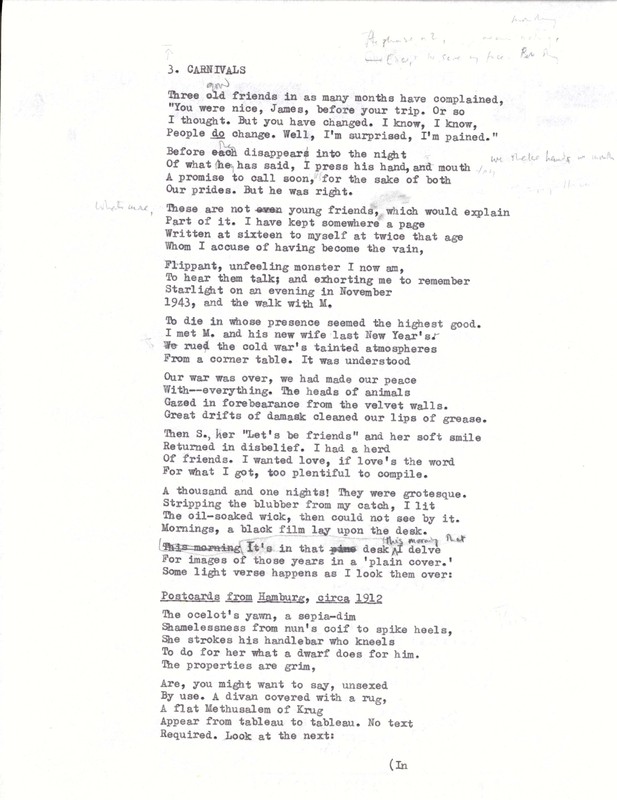

10) "3. CARNIVALS. Three old [good] friends." Pencil.

11) "3. CARNIVALS. Three old friends." Pencil.

12) "3. CARNIVALS. Three old friends." Ink, pencil.

Merrill uses the word carnival in the usual sense of a festival, such as the one in Rio de Janiero, and its etymological sense: "raising flesh," from Latin caro "flesh" and levare "lighten, raise, remove." Folk etymology (as in Manuscript 8) is from the Medieval Latin carne vale, "flesh, farewell!" (Online Etymological Dictionary.)

Manuscript 2 identifies the "Three good friends" that reproach the poem's narrator in the opening of "Carnivals" with a dedication:"for C., G., & K." The initial C refers to Claude Fredericks, and K to Kimon Friar. Langdon Hammer informs me that the the G refers to Merrill's friend Grace Stone. In James Merrill: Life and Art, Hammer suggests that Merrill's recently deceased friend "Taki" and Jane Bowles were also on his mind at this time. Taki is memorialized in "The Cure": "Chauffeured a truck; last Friday broke his neck / Against a tree." (Manuscript 7 contains some draft lines of the sequence's final poem on Scheherazade and the Sultan.)

Hammer describes the tensions Merrill felt with some of his friends:

Shortly before he left Athens Merrill received a three-page letter [June 1962], typed and single-spaced, from Friar that stated "I have watched what was refined and delicate in your character become affectation, mannerism, precious" (pp. 312-13).

In November Fredericks [renewed] a criticism he had often made: Jimmy’s sociability made him cold to those closest to him, unable to respond to what was most urgent and important (p. 321-22).

Hammer reports that Merrill replied to Fredericks,

"I wish I could come to grips with what lies behind the sweetly fluttering veil of your reproach, which I feel as a reproach not only from you but two or three other friends. Certainly there must be grounds,— in each case,— and it makes me sad because I realize I can only do what I do. I guess you would say I was a cat at heart, but I can remember when I was a dog and can’t easily account for the transformation. I was talking to Jane Bowles a month or so ago, off the top of my head, about how I loved no conversation better than the ones imposed in Greece by lack of a common language + common interests—'What does meat cost in the U.S.?' 'How many brothers have you?'— and she gave me one of her disquieting looks + said 'well, of course, you just want to be alone. What’s wrong with that?' I couldn’t say— I can’t now— Something does however seem wrong" (pp. 322-323).

He found himself responding [in "The Thousand and Second Night"] not only to the episode of Bell’s palsy, but also to Friar’s letter, Fredericks’s “reproach,” Jane Bowles’s remark, Taki’s death, and his own intimations of mortality, all pondered in the glare of Cold War fear and anxiety" (p. 323).