Edmund White on Kalstone and Merrill

Excerpts from Edmund White, The Farewell Symphony (New York: Knopf, 2010)

The author describes his introduction to Joshua (David Kalstone) by his mentor, Max (the poet, Richard Howard).

Among all the people Max introduced me to, only one, Joshua, became a close friend. In fact he became the great friend of my life, although at first I scarcely noticed him. His charm was oblique, his humor understated, his looks appealing only to the initiate. He wore contact lenses, but his eyes were so bad that he saw little enough by day and nothing by night, and when I’d send him off in a taxi at midnight after a drunken dinner and a nightcap or two, I had the impression I was pushing a wind-up soldier toward a precipice, for if the New York of Max, Tom and Joshua was a pinnacle of civilization, inhabited by these eclectic geniuses who knew everything and read books in every language in their calm, spacious apartments, the city outside was also as noisy as an Arab bazaar and as dangerous as a bear pit: the streets were piled high with uncollected garbage and pulsing with revolving police lights; on the fire escape beyond an open window lurked a house robber— or the shadow of laundry on a line; even the ground was just the thinnest layer of macadam poured over ten stories of hidden wires, sewers, subways, all rattling and steaming like pots on a stove. Only the lofty, raggedy roof gardens beside the forest of aerials and the slat-sheathed water tanks suggested another, tribal landscape— those roof villages or the dim inner courtyards flooded with pooling rain that pasted down layer upon layer of gingko leaves into a thickening vegetal collage of what looked like parchment, wax paper and butcher paper. (pp. 151-152).

Joshua had a mind I couldn’t fathom quickly. Early on I’d learned (perhaps because when I was a child we changed cities every year and I was faced each September with a new classroom of potential enemies) to characterize and seduce the people around me, but I could never figure Joshua out. Since the intellectuals I was meeting wanted to explain their work and to read it out loud, I was happy to listen (after all, most of them were at least part-time professors and used to a captive audience). My questions and welcoming silence could precipitate them into hours of glittering talk or recitation. Joshua, however, was quiet and curious. If someone like Max was always fearful that the tone might be lowered and spoke only on what he considered to be the highest plane, Joshua was delighted to gossip about friends, to speculate about the sex lives of the dancers at the New York City Ballet, to alert me to a good new restaurant reviewed in the SoHo Weekly News.

He was deeply suspicious of ideas and liked to quote William Carlos Williams’s injunction, “No ideas but in things.” Whereas I was convinced by almost any idea I could grasp and passed quickly from Structuralism to semiotics by way of a Gramsci-inspired Marxist cultural analysis, smiled at my enthusiasms and yawned at my lectures. He wanted to know how to prepare pasta alla puttanesca. He hoped to meet the ballerina assoluta Suzanne Farrell. He wondered what Lola was up to in the soap opera The Guiding Light. We had a very campy way of talking together that we deleted the minute Max or anyone serious was around. We gave all of our friends, men and women alike, female names and referred to them all in the feminine gender and referred to them all in the feminine gender. Joshua had been first in his class at Harvard as an undergraduate and had written an acclaimed doctoral thesis on the migration of the Petrarchan sonnet from Italy via France to England. He was considered one of the leading experts alive on Sir Philip Sidney, but the Renaissance bored him, although he quickly scanned articles every week or two in learned journals just to keep up with what everyone in his field was doing. No, what interested him were the poets whom he was meeting and whom he was beginning to write about.

"Eddie" is James Merrill.

His own life had been changed by Eddie— a poet, millionaire and gay man— who’d transformed Joshua by convincing him to buy contact lenses to replace his extremely thick glasses, and silk shirts and pale, pleated slacks to wear instead of the heavy, old-fashioned wool suits his father, a small-town tailor, had outfitted him with. Joshua and Eddie visited a tailor in Venice, a certain Signor Cicogna, every summer, and Joshua would come back with sports jackets in a fabric that in English is called houndstooth but in French (and Italian) “hen’s foot.” Or a black wool suit lined in red silk, which would cause Joshua, as he flipped his jacket open, to say in Italian with a sly little smile, “Priest outside, cardinal inside.” His new look lifted him out of the category of the dowdy academic into that of the smart man-about-town. At first Joshua— so wry, so unemphatic, smiling quizzically because he wasn’t sure he was seeing the right expression on the other person’s face— seemed like a charming extra in my new life, but soon I came to love him for the intimacy that sprang up between us as well as for all of his virtues, which were precisely the ones I lacked. I had a way of shamelessly courting and flattering people such as Max or Butler because I felt I was acting in a play, whereas Joshua took them seriously, he was at home in this New York intellectual milieu, this was his one and only life, and he wasn’t about to concede an inch to someone as high-handed as Max or as slippery and self-righteous as Butler.

Joshua had started out as a bookworm. He’d excelled in studies that had obliged him to learn Greek, Latin and Renaissance Italian and French. If he looked fifty when he was only twenty-five (I was shocked by his old photos) and back then had been both loveless and envious, at least he’d had the satisfaction of mastering his field and even writing an essay on Shakespeare’s sonnets that everyone still quoted two decades later. Anything judged remarkable that touched on Shakespeare, no matter how peripherally, repositioned the very cornerstone of our civilization— or should I say their civilization, since I could speak about it so pompously only because I didn’t feel part of it; I bowed my head before Shakespeare as one might stand or kneel in an unfamiliar church. I’d majored in Chinese, I’d been a Buddhist, my favorite college courses had been Buddhist Art and the Music of Bartók, I knew The Tale of Genji better than Hamlet, I’d never studied Marlowe, Sidney or Spenser (Joshua kept telling me there was no greater pleasure than reading The Faerie Queene but I remained unconvinced), I’d read all of Ibsen (even Emperor and Galilean), revered Knut Hamsun, and Colette and Nabokov were the writers I read whenever the world appeared colorless, but if I wept when I read Keats my eyes were dry when I perused Dante— dry or slowly drooping into deep sleep. If I was a public-library intellectual, someone who read without a plan and followed only his whims, Joshua was the real thing. I went with him one day to the university where he taught. Whereas Max bullied his students and hoped above all they’d consider him intelligent, Joshua was the good shepherd who gently prodded his flock toward the paddock. Max was exhilarating because he poured so much energy into every encounter and had a vaudeville extravagance about him. But he was also absurd with his swooping intonations, dictionary words, Inverness cape and deerstalker, and no one would have wanted to be like him— or if, bizarrely, the desire to emulate him had been awakened in some undergraduate breast, no one would have known how to go about copying such a preposterous style, so angular precisely because it joined a European erudition to a Midwestern bumptiousness (he avoided these two psychic and geographical extremes in favor of New York, where no one could judge him because no one could quite place him, and where energy, a quality he bristled with, was prized more than polish). (pp. 151-54)

But Joshua, during all the years and in all the different countries and contexts I knew him, was always more admirable than intimidating and esteemed more for what he was than for what he said or did. Any guy in his classroom was fitter, more agile, better looking than he and abler at seeing the world around him, but his very frailty only pointed up the strength and suppleness of his mind and the high finish of his manner. Anyone could tell right off that Max was a tyrant; he could make it disadvantageous, even perilous, to disagree with him. But his friends and students didn’t fear Joshua. No, they longed to please him. Joshua’s hands gently molded the air when he spoke. He sat on the edge of his desk closest to his students, which suggested without demonstrating casualness, since his performance was so highly organized that nothing about it went unpremeditated. He cocked his head to one side and listened to his students, whom he sometimes deliberately pretended were saying things more intelligent than they intended. Everything he said was designed to lead his audience to a more focused vision of Shakespeare’s world, an almost pictorial apprehension; as Joshua spoke one could see golden clouds banked in Tintoretto-blue skies above Cleopatra’s sun-baked walls. For Joshua the woods in A Midsummer Night’s Dream or As You Like It were a charmed precinct in which young lovers would try out new (even androgynous) roles before returning, wiser and more humanly gendered, to the city or court.

Perhaps that’s why Joshua loved the New York City Ballet, since it, too, showed us a Utopian society in which a man and a woman wordlessly moved through the enchaînements of other couples under the charged regard of spectators, symbolized by the lateral lights raking them from out of the wings. Joshua admired the ballet criticism of Edwin Denby, who had a Shakespearean vision of dance as both urban and Utopian. And Joshua adored “cruising” the main lobby of the newly opened State Theater, although his prowling and looking were more social than sexual and even under the bright lights he could scarcely make out who anyone was. As I squired him about the lobby from the bar onto the vast outdoor balcony he’d make funny remarks about all the celebrities we were passing; he’d give me their pedigrees, tell me how they were related to each other— and then realize he’d conjured up the wrong person. Perhaps his blindness stimulated his imagination and permitted him to construct better plots, nobler lineages, more amusing social conjunctions. Like so many people I’d been taught from the very beginning that society was entirely negative: a hypocritical, gossipy artifice from which sincerity was necessarily banished and intimacy absent.

But Joshua taught me (though only because I wanted to imitate his example, not because he ever tried to convert me to his beliefs)— Joshua taught me that society provides the necessary amplification of our private thoughts and acts. We gay guys had gotten things exactly the wrong way— we made love in public (in trucks and baths and backrooms) but shared our thoughts only in the confessional of the tête-à-tête, preferably over the phone in which the spirit was entirely disembodied and all that remained of communication was a crackling silence or a tinny, transmitted voice. Of course even so we were better attuned to urban possibilities than heterosexuals, since at least we were always cruising the streets. Joshua’s Utopian expectations of society never occluded his awareness of its more usual grotesqueries. “It’s simply past belief,” he’d tell me during our morning phone call, recounting some new outrage that on my own I would have accepted as normal behavior. “He’s gone too far this time,” he’d say, and then the suppressed laughter in Joshua’s voice would bubble over or he’d start munching his rye crisp or he’d tell me what was going on in the street below— usually pure invention, since Joshua saw only what he imagined. (pp. 154-155)

White discusses Joshua's friendship with Eddie.

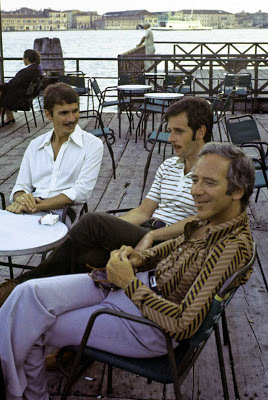

At the end of June Joshua was planning to sail to Europe with Eddie. I was jealous like Janus— jealous of Eddie for spiriting Joshua away, jealous of Joshua for his intimacy with this famous poet. For Eddie had in the last year, with the publication of his epic, become the most respected American poet of the day, although he’d long been the most notorious, since he was a millionaire whose childhood had been illuminated by the glare of grotesque publicity— a suicide, a suspected murder and especially the twinned themes of custody and alimony, love and money. Joshua and Eddie had been friends since they’d first met ten years earlier on a train. At that time Eddie had yet to win his first national book award and Joshua was just an assistant professor at Harvard, teaching in a celebrated program, “Humanities 6.” Joshua had managed to invite Eddie to give a reading at Harvard and though Eddie was too much an old-fashioned aesthete and dandy to be grateful for anything so public and transitory as an appearance in no matter how august an institution, the favor was registered if not mentioned and it lent the right tone to a friendship that quickly flourished for an altogether different reason: Joshua had a sense of fun.

He’d make the pilgrimage on a weekend once a month to Eddie’s house in a New England village, a house that would have been perfectly ordinary except that every object in it had figured in an unforgettable poem. There Joshua and Eddie would cook pasta recipes Joshua had brought back from Italy, reread Elizabeth Bowen’s To the North or Eleanor Ross Taylor’s collection of poems, Welcome, Eumenides!, listen to a recording of “the boys” (the duo-pianists Smith and Watson) playing Fauré’s Dolly Suite, jaunty and melancholy passages of this faux-naïve music for a sophisticated child scored the light-fingered dynamism underlying the apparent indolence of their long mornings established by the Hu Kwa tea steeping in the blue and white pot, the rustling of their silk dressing gowns, the blue smoke rising from Eddie’s single Gauloise of the morning, the scattered pages of the TLS and by the combined smells of the cigarette, the smoky tea and the pot-pourri in the entrance hall that Eddie kept refreshing by soaking the dried flowers with drops of orange essence.

In the winter they’d go out for long walks down to the harbor, then crunch their way back home through the snow that the evening was already turning blue. They’d beat their hands to stay warm and smell the smoke from log fires, so sad because it suggested family life. They’d quote lines from Elizabeth Bishop in an antiphony made visible by the misty breath trailing from their mouths, look up to see the ruby lamp hanging above Eddie’s upstairs dining room table. In the summer they’d take the sun on the highest terrace and peer down into a garden where a famously hermetic novelist could be seen pacing back and forth alone behind his agent’s house (“ We’ve seen him!” they whispered to the others, triumphant, that evening over cocktails. “That is, we’ve sighted his limp. He has a limp. I’ve seen him, you haven’t. What? A black turtleneck”). If Joshua had been the usual American academic— pedantic, incurious, obsessed with departmental politics— he could never have become intimate with Ariel-Eddie. But Joshua never lectured, loved gossip, always won at charades, knew how to tease the local ladies, several of whom had already made reluctant star turns in the magic theater of Eddie’s verse. Joshua had found just the right way to cite Shakespeare or Sidney, with unsounded depths of veneration that didn’t paralyze one’s own playfulness (in a charade Joshua acted out, none too convincingly, the line, “Ill met by moonlight …”). (pp. 203-205)

Eddie, who was almost a decade older than Joshua, liked to fuss over Joshua’s fragile health (“ Sit over there in the high-backed chair, there’s a bit of a draft hitting the loveseat, though why I’ll never know, must be the churning of angels’ wings”). Eddie also upbraided him for his laziness (“ At least I have some laurels to rest on,” Eddie said, “whereas your mere two titles are rather scant foliage, though dense enough, admittedly, to seat you comfily for life in the Harriet Smith Silverstein Cushy Chair of Renaissance Studies”). “Some of us have to work for a living,” Joshua stoutly called out, even if he was terribly hurt by Eddie’s harping on his slender output and the name of his absurd professorship. “Ah, yes, whereas I merely live to work,” Eddie replied. He always had the last word. Of a new Japanese painting he said, “It’s the usual swirls before pines.” When he came back from a trip to Asia and his first taste of opium, one of the ladies asked him if it caused impotence and he replied, “Poppycock.”

The occasionally soggy puns in his conversation and his sometimes tedious adherence to all forms of parlor games were five-finger exercises for the flashy word play and formal trickiness of his long poems, in which virtuosity was always transposed up a note into wisdom. No wonder he liked French piano music, which at its best kept the same proportions of parody, parlor fun and stabbing beauty. “How can he be so cruel?” Joshua asked me. “Teasing me about my output, when he knows I suffer terribly from writer’s block. And of course I could point out that teaching is grueling work, not that he’s ever had to think about work. The other day when I told him I’d received a raise and was now earning fifty thousand dollars a year, I might as well have been discussing shekels or drachmas. He blinked and said, ‘Is that considered a lot?’ ” Although I’d read little contemporary poetry since university days, Joshua was immersing me in it again. (pp. 205-206)

[Eddie] couldn’t resist allegorizing even his own parents’ divorce, which instantly became a quarrel between Mother Earth and Father Time, a marriage on the rocks. Joshua was uniquely qualified to understand this kind of autobiography. If he would have been titillated but left speechless by shocking personal revelations, Eddie’s approach, which harked back to Dante’s La Vita Nuova, reconciled the Renaissance with the second half of the twentieth century. Dante had alternated exalted but abstract sonnets with short, straightforward prose paragraphs narrating his various meetings with the historic Beatrice in the streets of Florence. Eddie melded the poetic and the prosaic, the symbolic and the literal, the religious and the frivolous into verses that glowed as though the glassblower had just pulled them out of the furnace, puffed and twisted contrasting colors into shapes, then pinched them off and set them aside to cool. Since I’d studied Chinese at the university I should have been used to the idea of generating endlessly proliferating commentaries on the classics, but something in me was alternately scandalized and charmed by so much of Joshua’s careful, resourceful attention being focused on just a few lines of poetry.

I don’t want to suggest that I was a free spirit, an artist, and that Joshua was “dry” and “pedantic” just because he was employed by a university and I wasn’t. On the contrary, my skepticism about Joshua’s work was a bit philistine, whereas Joshua’s method was anything but mechanical. No idea was driven into the earth and no theory was allowed to crowd out intuition, his intuition, which he began and ended with and to which he remained faithful. Joshua and I would eat our green beans and rare steaks, our “diet food,” at Duff’s on Christopher Street while downing a bottle of white wine. From there we’d go to the Riv and drink two stingers each, a sweet concoction of white crème de menthe, brandy and vodka. Often I’d accompany Joshua home and in his charming floor-through in Chelsea we’d talk till dawn about poetry over “splashes” of brandy on the rocks while listening to LP records of the music Balanchine had choreographed— Stravinsky’s Agon, Hindemith’s Four Temperaments, Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings. Our conversation would skip lightly from a discussion of the Wordsworthian Solitary to Elizabeth Bishop’s old fisherman in “At the Fishhouses” (“ There are sequins on his vest and on his thumb. / He has scraped the scales, the principal beauty / From unnumbered fish with that black old knife / the blade of which is almost worn away”). Or Joshua would show me a recipe in Marcella Hazan’s cookbook he wanted to try out. Or I’d tell him about my strategies for seducing Kevin.

One night we fell drunkenly in bed together but I didn’t want to be Joshua’s boy. I guess I wanted to be his equal, his friend. Joshua was clearly in love with me. At the door he’d cling to me a second too long and his lips would open when we’d kiss. I felt that he’d been waiting all the long, long evening just for this moment. I resented his insistence on this tribute, his “due,” which in my eyes invalidated his professions of friendship whereas to his mind love was the natural overflow of so much laughter, so many shared secrets. Whereas I was willing to tell anyone everything about my sex life, I was reluctant to confide my ideas even to my closest friends, not because I was proprietary about what lawyers call “intellectual property,” but because, well, I scarcely ever had carefully defined ideas and, as a novelist, I was more likely to form an idea in a dramatic context I’d invented, in a conflict between two characters, than in the abstract. But with Joshua I felt the need to share with him all my half-baked ideas, except those about a sexual temperament that excluded him (206-208).

When I arrived at Joshua’s one evening Eddie was already sitting there. I’d been anticipating this first meeting for weeks— at last I was to be introduced to my idol’s idol, the man sensitive enough to appreciate my talent and rich enough to help me. Eddie had brought along a little package of things he could snack on. “It’s all feng and shui,” he murmured, “and wu wei and yang and yin.” Suddenly he raised his hands and shook them and said in a high-pitched voice, “Lawdy, Miz Scarlett, Ah don’t knows nothing ’bout macrobiotics …” Eddie avoided looking at me and when Joshua wandered into the kitchen searching for ice, Eddie subsided into himself, a grumpy display of deliberately cruel unsociability that Joshua, of course, would have admiringly chalked up to “shyness.” I was intensely uncomfortable. I knew that Joshua considered Eddie to be not only the greatest living poet in English but also our sole candidate for immortality. What’s more, Eddie was fabulously rich and had set up a foundation for handing out grants to deserving artists. He was meant to be witty and worldly, but with me he seemed like a snake curled into a ball, the only sign of life a flickering tongue, for he licked his lips like someone who takes amphetamines. He and Joshua referred to a new diet they were both going to try.

Then they spoke about two of Eddie’s neighbors, a mother and a daughter, but there was nothing I could add. Finally Joshua “begged” me to read the first chapter of my Japanese novel, but we’d already conspired to spring it on an unsuspecting Eddie and so I just “happened” to have the manuscript with me. I read it in the deafening silence around me. Joshua’s eyes were swimming shut, although from time to time he sat forward in his chair, as though by putting himself in a state of precarious balance he could keep himself awake. Each time he lurched up out of sleep he smiled and pantomimed opening his eyes wide. From time to time I glanced over at Eddie to see his reaction, but he was nervously pressing the fingertips of one hand to those of another. When I’d finished the chapter he didn’t say anything. He just lowered his head at an enigmatic angle with a soft smile but no eye contact. (pp. 210-11)

We went to spend a weekend with Eddie in his New England village. Eddie read to us a poem he’d written to his goddaughter, the plump one-year-old child we could hear laughing and talking to herself in her playpen on the landing below, as she batted at the fish mobile dangling above her pillow. Fifteen years ago her father had been a handsome evzone in a white skirt, with a narrow waist and strong, hairy legs. He and Eddie had met in Athens and every stage of their love had been celebrated in poems with titles reminiscent of Cavafy or Rilke, a blend of heart-piercing nostalgia and a throbbing angelus of narrative and allegory. Now the Greek was a portly, balding family man of thirty-five and he and his wife and daughter lived downstairs. He was the janitor and caretaker and he also worked in a nearby pizzeria Eddie had bought for him. Once a month he came upstairs, tool in hand, to give Eddie a tune-up. His wife probably didn’t suspect a thing. She stayed inside, grew broader, smiled shyly, knitted baby things against the winter cold, made Eddie the lemon-rice chicken soup he loved. Joshua and I read the new poem for Cassiopeia, worked our way through its elaborate astrological conceits and consulted with each other. Finally Joshua, despite an admiration that bordered on awe, dared to say to Eddie, “Isn’t it … a bit … cold?” Eddie slapped his forehead and said, “Of course! I forgot to put the feeling in!” He rushed upstairs to the cupola that served him as a study and fiddled with the verses for an hour before he descended with lines that made us weep, so tender were they, so melting and exalted. That night, when we were alone, Joshua whispered, “A rather chilling vision of the creative process, I’d say. We must never tell anyone about this, since how many people would understand and forgive. (p. 239)

I went to Venice in June to visit Joshua. He told me that if I could pay my way over he’d pick up all my other expenses while I was there. I took a boat in from the airport. It threaded its way past abandoned islands and pylons bound together like asparagus held upright in a steamer so that the stems cook faster than the tender heads. I thought that if I were a painter I’d paint this vast pale blue dome— streaked with pale cirrus clouds. Now the horizon line was thickening and filling in with fantastic detail. We could see the pure spire of San Giorgio on the left, the lifted gold ball of the Dogana gleaming straight ahead of us and over on the right all the layered complication and panoply of the Riva degli Schiavoni, the church where Vivaldi was composer, the house where James finished Portrait of a Lady, the hotel where Georges Sand and Proust stayed, the Oriental filigree of the Doge’s Palace, suspended over a low, columned walkway, the soaring monument topped by a saint and crocodile, behind it the green-roofed ten-story brick campanile and, just to the right and beyond, the great clock with its two Moors striking the hours, both with bare asses and big dicks. And as the drone of our motors shifted softer, the hollow roar of thousands of milling human beings flowed in on us, the tumult of voices and shoes striking stone, the muffled busyness that suggested an undressed opera stage where a director was rehearsing a crowd scene with extras in street clothes. Guides with raised, colored umbrellas were trying to keep their different groups together (Joshua called them the pecore). Faintly, in the distance, an out-of-tune café orchestra was playing a palm-court version of “Strangers in the Night.” (pp. 276-77)

Joshua was transformed by Venice. In New York he was so blind he was always frightened crossing a street or walking through a dubious neighborhood at night (and which neighborhood wasn’t dubious?). But in Venice cars were banished and the steps were bordered by little white stones. He and I wrote in the mornings, the air redolent with espresso. Joshua could never sit still more than five minutes, nor could I. He’d be out on the back balcony inspecting the indigo-blue morning glories; for Joshua, their delicate beauty was contrasted with the military vigor of the Italian word for “climbing,” rampicante, which he loved to say. He had to hold the local Venetian paper, Il Gazzettino, an inch away from his eyes in order to read it. Or he’d show me the “disgusting” photo of the Pope with the count and countess, the owners of the apartment, who let it when they went away every summer to the Dolomites. I dropped my ballpoint and it rolled downhill; the marble floor was cracked and it tilted dramatically away from the Zattere side and toward the Grand Canal. The ceiling was low but painted a greyish-white and faded pink; the vices and virtues were ensconced along the cornice above their names in Latin; interchangeable and bored maidens alternating with amusing male caricatures stuffing their mouths or dozing or lustily grabbing a wench. The lesson to be learned was that vice was active, fun and individualized, virtue impassive and impersonal. Joshua would adjust the heavy shutters, their hinges unoiled and complaining; for a moment he’d be a dark shadow pressed against bars of light, like a cat stretched out on piano keys. We’d eat a green salad, wedges of fontina and gorgonzola and translucent slices of prosciutto, red and thin as a hematological slide, and dark, wind-dried beef, bresaola (so hard for us to pronounce with its gentle growl of unfolding vowels). Sometimes we’d laugh ourselves sick pretending to be middle-class Italian matrons who could scarcely stand each other but elaborately feigned mutual affection (“ Carissima!”). I think the idea was that we were fiercely competitive— and conformist— housewives, each sure that her kitchen was even more casalinga than the other’s. It wasn’t as though we were satirizing women we actually knew; we were simply performing a vaudeville routine ad nauseam (the nausea, too, made us laugh). (pp. 278-279). . . . Joshua was heading for the Cipriani pool, which was so expensive he could afford to invite me only two or three times. (p. 280)

… Joshua asked me to come to Venice for the last two weeks of August. When I arrived he told me he was positive [for AIDS] and had fewer than a hundred T cells, but his announcement struck me as utterly implausible. Joshua? He who’d made love to no more than twelve men in his whole life? Who’d always been too blind to cruise, too prematurely elderly ever to bed a fast-lane gay man? Of course I was only exposing my ignorant assumptions. AIDS wasn’t cumulative and it didn’t just strike the promiscuous scene-makers. “Have you lost a bit of weight?” I asked. “Alas,” he laughed, “not enough.” He was always dieting and though his skin now was waxy and white and stretched across his cheekbones in that tell-tale way, his lower body was still plump. The changes wrought by AIDS came ten times faster than those imposed by age (five decades’ worth of aging could be squeezed into five years) but still slowly enough that only someone like me who’d lived apart from Joshua and not seen him for a year could notice how his teeth had become more prominent, as though they’d slid forward a fraction, and his eyes had become hollower, as though they’d retreated, and the skin on his arms hung looser, as though it had already died. (pp. 389-90)

Phillip seems to be J. D. McClatchy.

Philip was efficient, confidence-inspiring. Beneath his tough-talking exterior he deployed an inexhaustible energy focused on Joshua’s real needs. Whereas we all felt inept and shy in dealing with doctors, lawyers and heterosexual family members, Philip summoned Josh’s brother to New York and reviewed the will, making sure everyone agreed on (or at least accepted) its terms. And Philip had found a clever graduate student to piece together Joshua’s last book, to pluck it like a divination out of the entrails of the abandoned computer. I stopped calling Joshua, nor did he phone me any more. The last time I’d spoken to him he’d seemed so confused, if gentle and kind, that I thought he must be close to the end. He wasn’t. Butler and Philip were disgusted with Lionel, who they insisted neglected Joshua entirely when he was left in charge over the weekend. “When Butler and I drop in on Monday morning it’s obvious that Lionel hasn’t been feeding Joshua. Of course Josh is just blissed out, always smiling, but you can see he’s dehydrated, Lionel hasn’t changed his diaper, and he’s left Joshua alone for long periods during which he’s gone out clubbing. It’s criminal behavior— and disgusting that he’s going to inherit fifty thousand dollars in cash, which he already knows about. He’d probably like to see Joshua die as soon as possible.” “Surely you’re exaggerating?” (pp. 404-405).

When I rang the bell to Joshua’s apartment, Philip— lustrously bearded, boisterously gloomy— let me in. “Well, I’m afraid you waited too long,” he called out, heartless and gentle, “there’s not much left. If you talk to him you might get a smile, that’s about all there’s left of cortical response, God knows what it means, probably just a reflex— typical of Josh that his last automatic response should be a smile.” In the front bedroom Joshua lay on his back in the blue and white pajamas I’d sent from Lanvin in Paris.

His face was so white, covered with still whiter patches on the temples, that he seemed carved out of a mushroom, a big pale shelf of mushroom growing out of the roots of a tree in wet ground. And yet, when I touched his hand, it was dry, each finger dry as a new, cool stick of blackboard chalk. Even with his lenses in he’d always had trouble seeing, but now, lensless, he could have perceived nothing but light and shadow and movement. Except his eyes looked fixed, glazed over. His nose had grown an inch longer. He was terribly thin (“ At last!” I could imagine him exclaiming with a laugh) and looked as though, like Kafka’s hunger artist, he could be mistaken for a bit of dust or straw and quickly swept up into a dustpan by an energetic hand. I said, “Josh?” He smiled, faintly, lifted his eyebrows, blinked encouragingly. His lips pursed slightly, as they always had, as though he wanted to meet the world halfway, not just hear its messages but also sip them, taste them. I thought, The Egyptians had the right idea, devoting whole lives to building tombs as big and luxurious as their palaces, mammoth launching pads for eternity, whereas even our richest men and women, who live in twenty rooms, or a hundred, are willing to be slid into a tomb no longer or wider than their lowest servant’s cot— which only shows no one really believes in a life after death. I wanted to build a monument of words for Joshua, big and solid, something that would last a century, although I doubted I had the ability. I wanted other people to know about his intelligence, which was sympathetic, even diagnostic, but never analytic: he could learn a poet’s language in just a few tries, as though he were one of those ethnolinguists who can entirely map out an unknown tongue in just twenty days in the Bush. He could also tell what were that poet’s preconceptions, preoccupations, points of unresolved discord, governing metaphors and link all that to his (usually her) most intimate experience without gossiping about the details of her or his life. He loved Shakespeare’s comedies for the same reason he loved Balanchine’s ballets (there on Joshua’s wall was a get-well card from Suzanne Farrell, the prima ballerina who was assoluta in his heart): both Shakespeare and Balanchine devised new combinations of men and women, of courtship and union, of assertion and accommodation, but transposed into a higher, purer key. (pp. 408-09)

When Joshua died, Eddie called me to tell me he’d communicated with him already via the Ouija board and that he was fine, on his first day he’d been given a lovely tea party by Wystan Auden and Chopin, and he sent me his love. Josh was very excited since he was scheduled to be reborn soon as a little brown baby girl in Calcutta. I laughed and hurried to get off the line, so offended was I. Soon afterwards I looked through all the letters I’d ever received from Joshua and I realized I’d been unworthy of him then, that he’d been sending them through time to me as I would become years later. (pp. 409-10) But even for Eddie the Ouija board became a drawing room game that turned sour. Before his own death from AIDS just last year, a depressed, emaciated Eddie told me that he’d followed the board’s instructions to go to a certain café in Athens where he’d be sure to meet the fat Indian girl who was Joshua’s reincarnation, but the child didn’t come. Eddie waited until two in the morning, when the café closed, but the child never showed up.

Nevertheless, a death without rituals is intolerable. Most people would do well to stick with church ceremonies, which are noble and full-throated in the right well tested places and even dull and distracting elsewhere in just the desired degree, but Eddie had a solemn, awed, fluent way of celebrating the great, hard moments. He swirled Joshua’s ashes from a gondola into the Grand Canal while reciting a poem he’d written for the occasion. I went back to the palazzo where Joshua had lived. The principessa had asked me to stop by. She led me up to the attic, which looked like the reversed hull of a war ship, all ancient, rough-hewn beams. There, in that maritime desolation, stood a little pile of Joshua’s things— dirty white trousers, sunscreen, the typewriter his computer had replaced, an old copy of a Beaux-Arts magazine, an extra fan. The principessa behaved as though it was, well, even legally necessary that I do something with these pathetic possessions, Joshua’s half-hearted pledge that he’d come back if not the next summer then the one after. I shrugged, even laughed a bit rudely, took the things away (did she think they were infected with the “Ides” virus?), and dumped them in the trash just outside the door. Joshua’s spirit was no more in these things than was our virus; his spirit was lodged in Eddie’s pages, in his own, even, I hoped, in mine. (pp. 412-413)