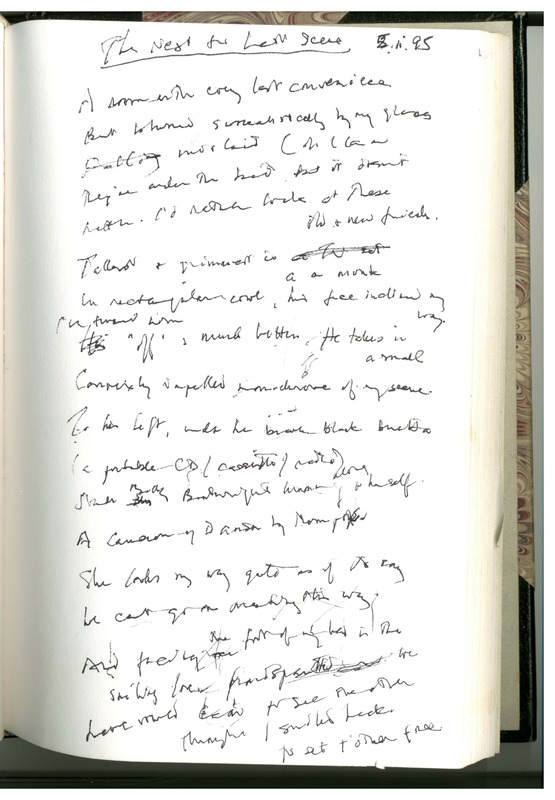

Draft of Merrill's Final Poem

Autograph draft of “The Next to Last Scene” by James Merrill, February 5, 1995. Written by Merrill in his journal from a hospital bed in Tucson, Arizona the day before his death. It begins with the line, “A room with every last convenience” and ends with “to set the other free.” Special Collections, Washinton University Libraries.

From Langdon Hammer, James Merrill: Life and Art (Knopf 2015), p. 790.

What happens when everyone else is gone? A writer writes. Now in his notebook, on a fresh page, in a tiny, trembling script (he had mislaid his glasses), Merrill underlines “The Next to Last Scene” and begins a poem under that title. It was unusual for him to title the first draft of a poem in his notebook: he must have known he would have just one chance to get this one down. He’d told Torren [Blair] “to feel your feelings in the presence of something in the ‘outside world,’ ” anything at all. In the darkening ward, he takes his own advice. What he sees around him is “A room with every last convenience”— dull objects of mere, mute life that his imagination will try to animate once more. The TV suspended above on the wall, “Tallest + grimmest,” turns into “a monk / In rectangular cowl.” Has he come to guard the poet, or summon him away? A snapshot of Billy Boatwright glances back at him wittily, “quite as if to say / we can’t go on meeting this way.” Last, “at the foot of the bed,” he sees the photo of himself beside his “smiling lover.” His hand crumbles as he fits in two sentences at the bottom limit of the page: “We have vowed each to see the other through. / I smile back to set t’other free.”

From J. D. McClatchy, "Braving the Elements" (originally appeared in The New Yorker, March 27, 1995), from The Borzoi Reader Online.

When Merrill's ashes were sent back to be buried in Stonington, a box of papers came along too. Among them was a poem called "Koi." Behind the house he had been renting in Tucson for the winter is a small ornamental pool of koi, the Japanese carp. The poem--the last he wrote, a couple of weeks before he died--is about those fish and his little Jack Russell terrier, Cosmo. Of course it wasn't written as a last poem, but circumstances give it a special poignancy.

Also sent home was his notebook. It's open now on my desk. He'd kept a series of notebooks over the years, their entries irregular, often fragmentary. Things overheard or undergone. Dreams, lists, lines. An image or an anagram. The writing--even the handwriting--is swift and elegant. But the last page of this notebook is nearly indecipherable. Suddenly, at the end, you can see the difficulty he was having: the script is blurred, and that may be because he had lost his glasses. His breathing too was labored. On Saturday, he'd been admitted to the hospital with a bout of acute pancreatitis. I spoke with him by telephone on Sunday, the night before he died, and asked about his breathing. He struggled to say that, though he'd been given oxygen, the doctors were unconcerned and scheduled his release. The rest of the conversation was banter and gossip and plans for the future: a cataract operation, the new Pelleas at the Met. His notebook, though, tells another, more anxious story. The last page is dated 5.ii.95, the day before his death. There are two dozen line, sketches for a poem to be titled "The Next to Last Scene." Typically it starts by looking around his hospital room, and opens with what in retrospect seems a heart-catching line: "A room with every last convenience." It glances at TV set, cassette player, smiling lover. He would often, when drafting a poem, fill out the end of a line, knowing where he wanted to go although not exactly sure how he would get there. He'd done so here. I can make out "To see the other through." And then, the very last thing he wrote, "To set the other free."

To set the other free. Who is this "other"? The longer I gaze at the page, the more resonant the phrase becomes. Is it everything beyond and beloved by the self: the man in his life, the world's abundance? Or all that burdens the soul, distracts the heart? The psyche? The imagination? Or perhaps he means--this has been the case for the last fifty years--the enthralled reader. It is still intolerable to think that there will be no more of his resplendent, plangent, wise poems, that their author is like the mirror ceremonially broken at the end of Sandover, "giving up its whole / Lifetime of images."